‘Nazi Town, USA’: It Did Happen Here

A PBS documentary about the German-American Bund in the 1930s has some startling lessons for the present day.

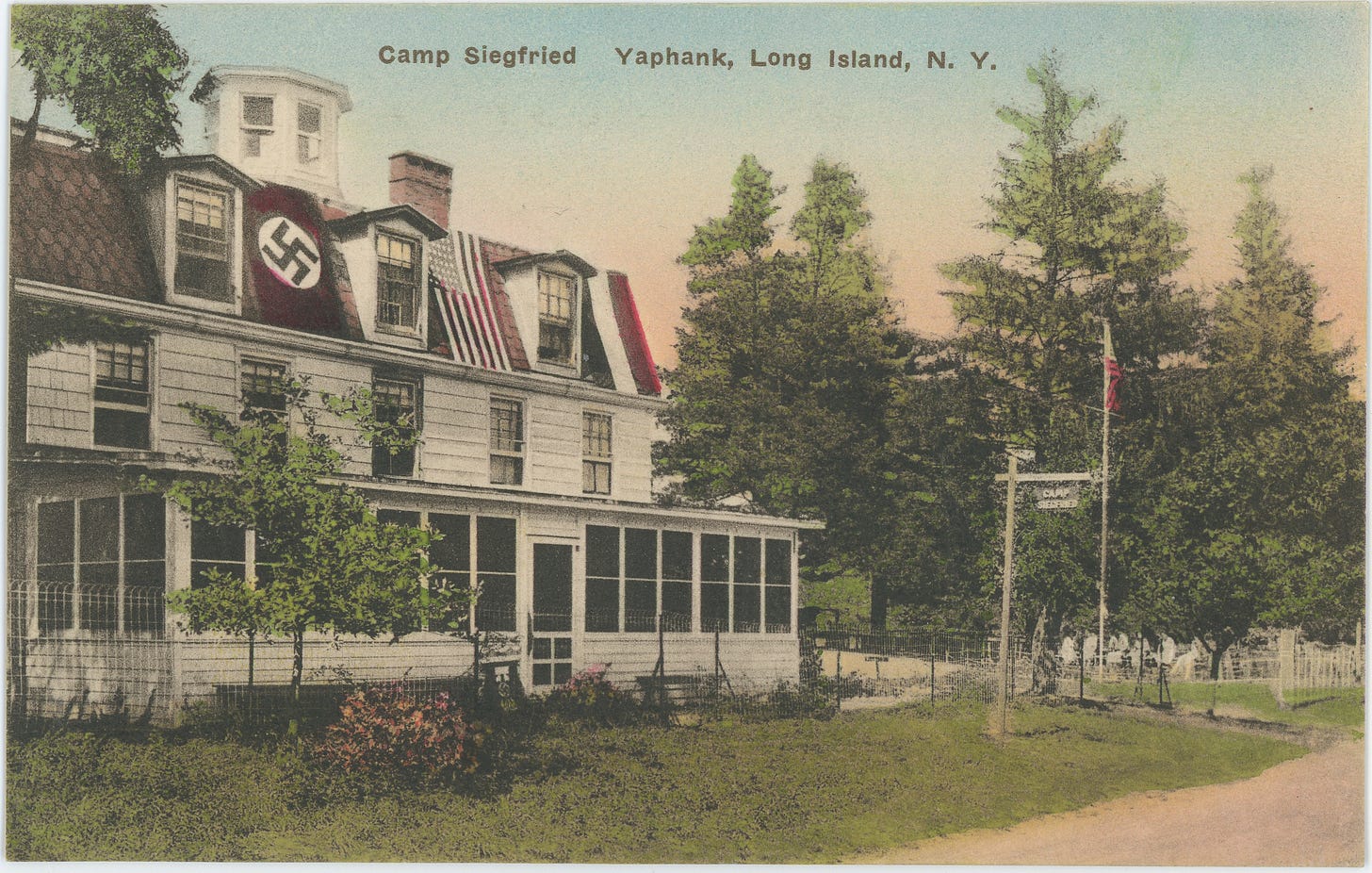

THE OLD BLACK-AND-WHITE FOOTAGE shows cheerful boys and girls exercising, swimming, dancing, and having fun at a summer camp. It has a very all-American look, with a disturbing twist: the camp actually hosts an American version of Hitler Youth from the 1930s, and the kids are marching with both American and Nazi flags. Thus opens the fascinating documentary Nazi Town, USA, which premiered on Tuesday on American Experience on PBS.

Nazi Town, USA, written and directed by Peter Yost, packs a lot into less than an hour of airtime as it explores a largely forgotten part of American history in the years preceding the United States’ entry in World War II: the surprisingly strong Nazi movement on U.S. soil. It started out in 1933 as an organization called Friends of New Germany, which disbanded in late 1935 after its openly pro-Nazi activities drew too much negative attention; its head, Fritz Kuhn, quickly formed a new group, the German-American Bund, whose ostensible agenda was to sell Nazism with a patriotic American face. The sight of rallies where the star-spangled banner flies next to flags featuring the swastika and the SS logo, and where thousands of men and women greet the American national anthem with the Nazi salute, is jarring.

The film argues that this Nazi movement, however foreign-influenced, tapped into some very American realities of the 1930s: the legalized racism of Jim Crow and the Ku Klux Klan (just past its heyday in the 1920s), widespread and often virulent antisemitism (Henry Ford and Father Charles Coughlin make brief appearances), surging anti-immigrant sentiment, and the popularity of scientific racism and eugenics. Bund activists like Kuhn genuinely thought, or at least claimed to think, that their program of gentiles-only white supremacy and traditional family values was fully in harmony with American patriotism.

Here, Nazi Town, USA might have taken a bit more time to explain why this attempt to grow an all-American Nazism or fascism didn’t take. For one thing, the Bund advocated dictatorship, which—to say the least—is a bit problematic if you’re trying to present yourself as championing the American way of life. (The Constitution and the Bill of Rights have a few things to say on the subject.) For another, despite the mainstream prominence of racism and antisemitism in the 1930s, America was even then a rich and complex canvas in which those ugly phenomena coexisted with powerful liberal and universalist strands rooted in the American founding.

Those founding ideals were likely among the reasons that even people who shared or at least abetted their era’s casual prejudices often shrank back in disgust when confronted with those prejudices in their stark and brutal form of naked hate. Exposure to sunlight, such as a series of articles by a pair of undercover reporters in the Chicago Daily Times, seriously damaged the Bund. Ethnic, racial and religious diversity played a role as well: the Bund had to contend with an influential Jewish community, particularly on the East Coast where it was most active. (The film has little to say about American Nazi activity on the West Coast and the story of the fascinating undercover operation to thwart it.)

WHILE THE GERMAN-AMERICAN BUND ultimately and quite resoundingly lost the battle for American public opinion, it did at one point have as many as 100,000 members and made some surprising inroads into American life. Perhaps the most jaw-dropping factoid in Nazi Town, USA is that Camp Siegfried, the Bund’s summer camp in Yaphank, New York, actually had its own train on the Long Island Railroad, “The Siegfried Special.”

The Bund was dissolved in December 1941 after the United States’ entry into World War II; by then, however, it was already in decline. Its high-water mark was arguably the infamous massive 1939 rally at Madison Square Garden which featured antisemitic gibes at President Roosevelt and a huge portrait of George Washington surrounded by American flags and swastikas. The journalist Dorothy Thompson heckled from the audience; a Jewish protester stormed the stage and was beaten by Bund thugs; and the number of participants inside the arena was dwarfed by the number of anti-Nazi protesters on the streets surrounding the Garden, by perhaps five to one. That event painted a target on the group’s back; Kuhn went to jail after an investigation uncovered that he had embezzled almost $15,000, a pretty substantial amount for that time, to spend on his mistresses.

If that detail will have ironic modern-day echoes for the viewer of Nazi Town, USA, so will many others—such as Nazis and Nazi sympathizers donning the mantle of free-speech champions. (There’s a brief clip of a man hawking the newspaper of another pro-Nazi fascist group, the Silver Legion of America, with the headline, “Free Speech Stopped by Jew Riot.”) Modern-day debates about free speech and extremist views would have been familiar to people in the 1930s, when some advocated hate speech laws to curb groups like the Bund while the American Civil Liberties Union opposed them on First Amendment grounds. Meanwhile, the case for “punching Nazis” was given a very literal application by Jewish boxers—and, sometimes, Jewish mobsters—who had no qualms about shutting down Bund meetings and rallies with their own brand of persuasion.

While Nazi Town, USA doesn’t force modern-day parallels, they certainly suggest themselves. (Watch for the moment near the end where Charles Lindbergh is seen saying that we can’t help Britain win its war against Germany and shouldn’t be offering assistance: substitute Ukraine and Russia and fast-forward to 2024.) At the film’s conclusion, University of London professor Sarah Churchwell says that nationalist movements are never foreign and always homegrown. In that sense, it’s not clear whether the Bund was truly an American Nazi movement: it was inextricably linked to a foreign power, and it’s not clear how much influence it had outside the German-American community. Should we see Donald Trump’s truly homegrown “Make America Great Again” movement as a fascist one? The Bund is too different to provide an answer to this question. But an observation made early in the film by historian Beverly Gage is scarily relevant:

In the 1930s, lots of Americans thought the whole social order was about to collapse. Capitalism, democracy—they were done for, and something else was going to have to come along to take its place. And a lot of people thought that was going to be fascism.

(A lot of others, as the film notes in passing, thought it was going to be communism, another mass-murder ideology.) Nazi Town, USA is a fascinating and informative reminder that we don’t live in a uniquely terrible time—and that when a lot of people start thinking that the liberal social order is collapsing and can be replaced with something better, things are going to get ugly and terrible.