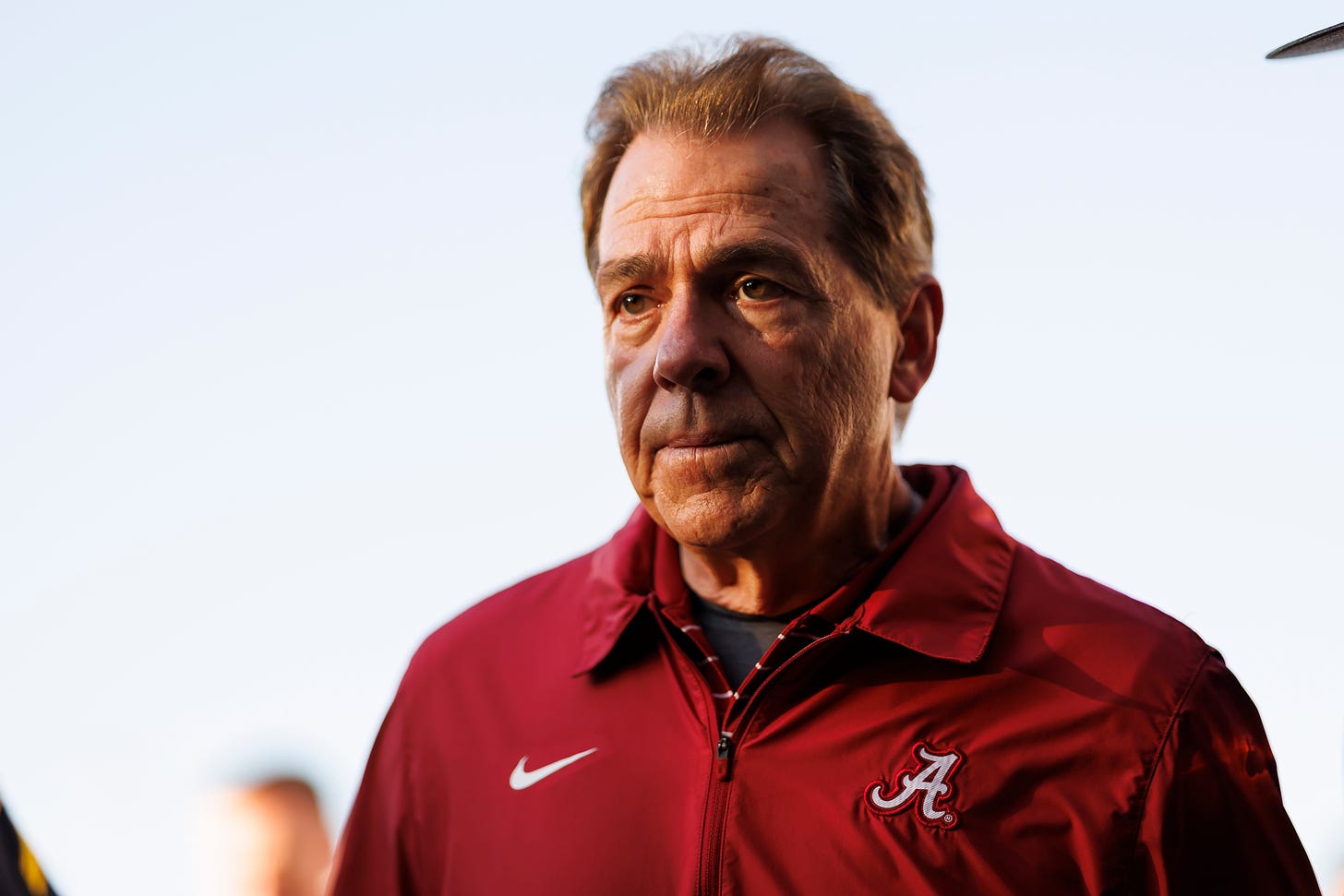

Nick Saban Was Right

During his time leading Alabama Crimson Tide, the legendary coach was right on the big questions facing college football.

THE WORLD OF FOOTBALL WAS ROCKED last week by the news that three legendary coaches—Pete Carroll, Bill Belichick, and Nick Saban—were leaving their positions. Carroll was let go by the Seattle Seahawks, Belichick agreed to part ways with the New England Patriots, and Nick Saban announced his retirement from the University of Alabama Crimson Tide, my beloved alma mater. While Carroll and Belichick have indicated a desire to remain in coaching and are likely to find new jobs soon, Saban’s retirement seems permanent.

Known for his cantankerous posture with players and media alike, Saban has never been shy with his opinions on the state of college football. His rivals disdained him as much as his fans revered him, listening with special attention to his prognostications about the future of the sport. In time, the whole world of college football—and by extension, all college sports—will come to realize that, on the major questions of his tenure, Saban was right.

Of the three big questions Saban got right, the first was about the change of play within the game itself. In 2012, Alabama faced an upstart Ole Miss team that played with an up-tempo, no-huddle offense, managing drives of 13 and 16 plays with severely limited defensive substitutions. The week after the game, Saban asked, “Is this what we want football to be?” His concern wasn’t merely aesthetic—it was about the effects of such offenses on player safety. But he acknowledged that his team would adjust as necessary. Critics and rivals accused him of whining, dismissing him as an old-school coach out of touch with innovative styles of play.

Fans of the Crimson Tide later observed that Saban wasn’t offering a complaint, but a warning. He agreed to play ball. Since he hired former college and NFL coach Lane Kiffin as offensive coordinator in 2014, Alabama’s offenses haven’t looked the same. Though Kiffin has gone on to a successful tenure at Ole Miss, he and his successors under Saban compiled a 127–14 record over the next decade, eight College Football Playoff appearances, seven Southeastern Conference championships, and three College Football Playoff championships. Three of their star players in that time won the Heisman Trophy.

Yet Saban’s warning spoke to a fundamental reality. Football is a defensive game at heart. That same decade brought three CFP championship losses for Saban and Alabama, all of them to teams with a dominant defense that slowed down Alabama’s vaunted offense. Only one of those—2018 against Clemson—was a blowout, but in each loss, Saban’s belief in the defensive nature of the game was validated.

SABAN WAS ALSO CORRECT about two changes in the structure of the sport off the field, specifically the loosening of restrictions on the transfer portal and the compensation of players for the use of their names, images, and likenesses (NIL). Saban was never opposed to bringing in players from other schools via the portal. His 2015 national championship team was led by quarterback Jake Coker, who transferred from Florida State. Many of the other players Saban accepted as transfers in the last decade have gone on to play in the NFL. He also recognized the reality that some of his own players might leave for greener pastures.

Yet even as Saban took full advantage of the transfer portal, he also knew its limitations. Just as an NFL team is most successful when it builds its roster through the draft and long-term development, using free agency as a means of filling temporary gaps and needs, college programs are best served by recruiting and developing players from high school.

When college teams focus on developing the players they recruit, both the teams and the players benefit. In countless interviews and press conferences, Saban reminded fans that college players were very young men whose maturity levels varied. In true Aristotelian fashion, they needed molding into the kinds of players who could succeed on the field—and the kinds of people who could succeed off it. Several players who went on to play in the NFL fondly remembered his mentorship. Saban lamented that it was hard to get through to players when they jumped ship after two years. He’s not alone on this point—other coaches are noticing how difficult it is to keep a roster intact year after year. This doesn’t serve anyone well, least of all players.

Eased restrictions on transfers and the millions top college players could make by selling their NIL rights combined in explosive fashion. The hope of dropping the NCAA’s NIL restrictions (which the U.S. Supreme Court ordered in 2021) was that players might see some compensation from endorsements and autograph sessions similar to professional players. The reality has been that fans—both small-money and big-money donors—have contributed to a school’s NIL collective, which is required to operate independent of the football program and its coaching staff to provide players with compensation. Despite that supposed wall of separation between the schools and the money, coaches are being inundated with demands for compensation, often by players who have yet to prove anything on a college field. The result has been to give players what they want, but left coaches and fans in a constant state of flux. Saban was never averse to players earning money, but he often warned that money alone would not create parameters for a player’s success, nor would it serve the long-term interests of college athletics.

AS A COACH, SABAN WAS NEVER BEHIND THE CURVE. His defenses were innovative and tough, and just as it looked like an offense might pass him by, he adjusted. He understood not only the strategy and mechanics of the game, but the dynamics of the world around it, driven by trends that were both obvious, such as technology, and obscure, such as changing recruiting territories. (Not as many offensive linemen in Nebraska anymore!) At his core, Saban remained a traditionalist who understood the thing that made college football unique—what separated it from the NFL—was a fan’s loyalty to a place. It was the school, the jersey, and all the traditions that Saturdays brought with them. If the game were to become a constant stream of players drifting from one school to the next, fan interest would wane. Not permanently, but enough that the world that had been built around the game would likely decline—and all but the most gifted players would suffer most of all.

In many ways, the changes in college athletics since Saban started his career in 1973 have been welcome. I love that I can watch practically every sport involving my alma mater, from football to volleyball. I love that athletes can be recruited not just from around the country, but around the globe, and even a football program as prestigious as Alabama has recruited unheralded high school players like Josh Jacobs and Eddie Jackson and helped them become successful professionals in the NFL. But Saban understood—still understands—that not all progress is for the better, and not all opportunities bring freedom. Saban has often spoken of the “illusion of choice” that many athletes have that there are many paths to success, when the reality is that hard work, dedication, and discipline are never optional. The same is true for the sport itself—college football can only exist within certain parameters. Too much change brought on too quickly risks morphing the sport beyond all recognition. Saban’s caution wasn’t just about self-preservation—as if he needed the help!—but about maintaining the game for all the players and coaches who have fed their families in its practice and the fans who have built lasting memories in its thrall.

For years, Saban has suggested that college football needs a commissioner who can help sort through the myriad issues facing the game in a way that’s neutral among the competitors but fierce in defense of the sport. Perhaps that is a role that Saban himself could one day fill. Whether he does or not, coaches, players, and fans would be well served to heed his words when they are offered.