Here’s Why a ‘No Labels’ Campaign Could Be Even Worse Than You Thought

The group is playing with fire—and might burn the House down.

NO LABELS, ROBERT F. KENNEDY JR., AND CORNEL WEST are all right about one thing: the two-party system in the United States is a problem.

As any pro-democracy, anti-Trump conservative can tell you, it’s not great that we have only two options. The fact that voting against an authoritarian candidate often by definition requires voting for the Democratic party is hardly a hallmark of a thriving democracy.

We all know this. It’s just a fact of this moment in American history.

No amount of wishful thinking about a third-party ticket can change the reality that in 2024, the only viable presidential choices will almost certainly be a Democratic candidate who is willing to abide by the rules of democracy and a Republican one who seeks to overthrow them. Because Donald Trump is so extreme, any mainstream third-party candidate can only splinter the pro-democracy coalition. We can wish all day that it weren’t true. But wishing doesn’t change the world as it is.

The reality is even harsher. It’s not just that a third-party ticket can’t win or that it would be likely to help Donald Trump—although both of those things are true. It’s that even if a third-party ticket succeeds, meaning it wins any states, it could cause an even worse disaster.

Why? Because under the Constitution, whoever gets the most votes in the Electoral College is not automatically elected president. If no one wins a majority of electoral votes—at least 270—then the election results are functionally voided and the House of Representatives picks the next president in a “contingent election.” Given how closely divided the country is, it’s possible that we could be in precisely this position if a third party wins even a single state.

Does this scenario have only a small probability of happening? Yes. But in the last few years we’ve seen a fair number of “unprecedented” things come to pass, so it’s important to game this out.

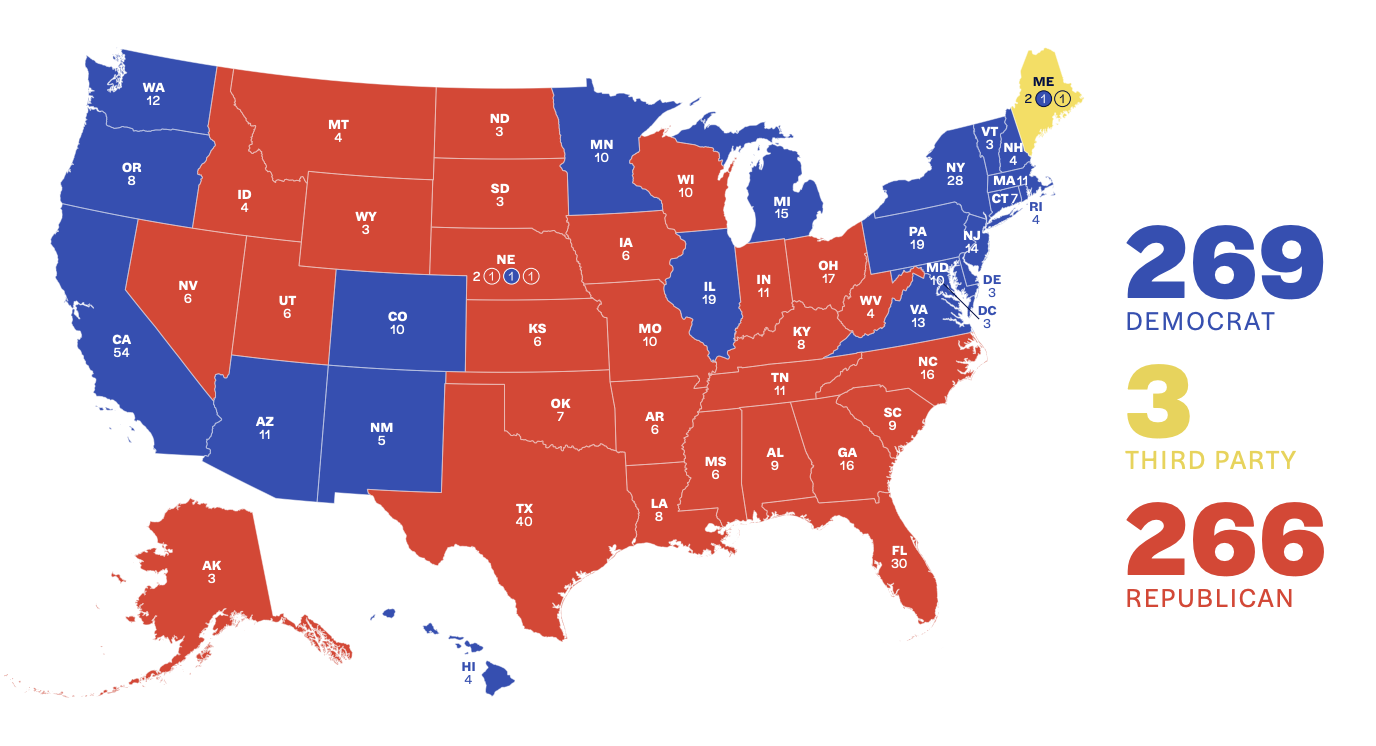

Consider this electoral map—just one of several plausible outcomes in 2024:

Here’s how the map above could become a reality: A candidate running on the No Labels ticket laser-focuses on Maine, whose independent electorate, allocation of electoral votes by congressional district, and use of ranked-choice voting all make the path to victory easier. With RCV, a centrist, independent candidate is very likely to be most voters’ second choice, so he or she would only have to beat one of the other candidates, not both. (Usually this is a good thing.) The No Labels ticket only has to win three of four electoral votes in Maine, while Biden and Trump each take a few battleground states. No one would hit 270.

Or consider this possibility:

This map could become a reality if a No Labels ticket led by a Republican (maybe former Utah Gov. Jon Huntsman) wins the three-way split in Utah (where Evan McMullin won nearly a quarter of the vote with little organization or funding in 2016) and Alaska (which has elected independents twice in statewide races since 2010, and which now also uses RCV). Again, no candidate would have a majority in the Electoral College.

Are these outcomes more likely than No Labels simply spoiling the election in Trump’s favor in a few key states? Certainly not. But are they plausible? We wish they weren’t—but they definitely are.

A contingent election would be extraordinarily bad

YOU MAY HAVE NOTICED that in one of those two scenarios, No Labels is likely taking away electoral votes from the Republican, not the Democrat. That does not mean a contingent election would tilt the scale towards Democrats. In fact, it only makes the contingent election scenario more chaotic.

Imagine this: As in the two maps above, Biden has more Electoral College votes but doesn’t have the 270 needed to win because No Labels kept both Biden and Trump from meeting that threshold. How would the contingent election work?

The Twelfth Amendment mandates that the House pick the president from among the top three recipients of Electoral College votes. In making its choice, the House votes by delegation, with each state getting one vote. Republicans currently control 26 state delegations, and are almost certain to maintain that control after 2024. Their choice is all but ensured. (It is the newly sworn-in House that would be picking the next president, but if recent elections are any guide, that likely just means an even more extreme Republican conference.) Even if Trump finishes a distant second in the popular and electoral vote, nothing would stop House Republicans from putting him back in the White House.

But that’s if things go smoothly. Perhaps more important to understand is that there is no clear process to run a contingent election. There are no federal laws governing contingent elections, beyond a sentence and a half in the Constitution. Key decisions—like how state delegations vote (plurality, majority, or supermajority, etc.), whether votes are by secret ballot, what constitutes a quorum, and so on—would have to be decided by the House in early January 2025. Unlike the election of a speaker, which happens at the start of each Congress in accordance with precedent and House rules, or the counting of electoral votes, which is governed by the Electoral Count Reform Act, in a contingent election the House would face a contest of the highest possible stakes for the first time in 200 years and have to write the rules as they go along. In a matter of days.

Remember, we are talking about a chamber that nowadays has great difficulty doing the basics of keeping the government funded on an orderly basis. And this would be a moment with huge openings for abuse, obstruction, or sabotage—by either party—where there are few guardrails and no legally mandated outcome. The chaos could dwarf that of January 6th.

And God forbid the winning candidates dies. If a candidate passes away between December 14 (when the Electoral College convenes in each state) and the end of the contingent election (presumably sometime the following January), he or she cannot be replaced. The House still must pick from among the top three candidates to receive votes in the Electoral College. There is no mechanism for replacing a dead candidate in such a circumstance, even with their running mate.

Scary stuff that No Labels is flirting with.

Real change has to happen bottom-up, not top-down

The unfortunate truth is we live in a strict two-party system, and there’s no meaningful, non-spoiler role for third options . . . yet.

That doesn’t mean we can’t get there. But we can do so only by reforming our democracy to allow for more parties and more options from the bottom up. This may not be as enticing as a savior, top-down presidential campaign, but it’s way more likely to work—and to avoid blowing up our democracy in the meantime.

There are real, meaningful reforms that can break the two-party doom loop, and bring third (and fourth) options onto the table. In the long term, this means implementing such reforms as multi-party, proportional representation for Congress. Proportional representation would turn the political center (and center-right) from the marginalized force it is today into the linchpin of any governing coalition, as centrist candidates would have the ability to win elections without support from either extreme. And proportional representation would likely have other benefits as well, such as diminished polarization, the end of gerrymandering, and better representation for various groups. Plus, once we have more parties in Congress, the presidency would become a much more open game—a contest between shifting coalitions fighting to secure a governing majority, not static blocs driven by base turnout.

In the shorter term, though, we can at least provide a better, more constructive role for third parties by re-legalizing fusion voting, both for Congress and the presidency. This once-widespread practice allows third parties to co-nominate a candidate with a major party. Historically, this gave third parties like No Labels real, meaningful leverage over politics, including at the presidential level—negotiating their support in exchange for policy concessions—without having to run a protest candidate to bring attention to their priorities and demands.

Just because we are unhappy with how our democracy works does not mean we should risk burning it down in frustration. As maddening as it may be, this is the reality we live in: To keep our republic, we need to build a broad, cross-ideological coalition that votes together when it matters most. We absolutely should think and talk more about the political system we want to have in the future—but we can’t ignore the world as it exists today.