No Wonder They Keep Coming

The Kino Border Initiative is one of the few places migrants can escape misery and cruelty on their journey north.

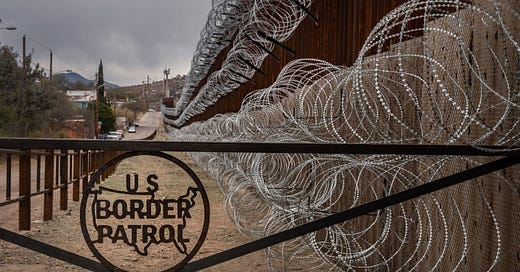

The Nogales border crossing is by no means the busiest. The terrain is unforgiving desert, with mountainous high ground on the Mexican side controlled by the Sinaloa Cartel. The whitewashed cinderblock building with one purple wall looks a bit like a warehouse as you approach it from the Mariposa border crossing that separates Nogales, Arizona, from Nogales, Sonora, Mexico. Inside, the large auditorium-like room is filled with men, women, and children who’ve just finished breakfast—perhaps their first real meal in days.

Most of the migrants have come from the American side of the border, sent back to Mexico after being apprehended and detained in the United States. Others have just arrived at the border, mostly from southern Mexico, Guatemala, or other parts of Central America. The latter are noticeably quiet—and thin. Guatemala now ranks sixth in the world in malnutrition, as climate change and last October’s hurricanes have destroyed the subsistence farms and small businesses that provided livelihoods for chronically poor families.

They have arrived at the Kino Border Initiative, a nonprofit, bi-national organization run by the Jesuits and the Sisters of the Holy Eucharist, along with several other Catholic groups. They’re here because they’re desperate. Most are fleeing gangs, cartels, and extreme poverty in their homeland, hopeful that they might build new lives in the United States. Instead, they have landed on the doorstep of KBI, where they can be safe for at least a few hours, eat a meal, and shower. A small handful of mothers with their young children will sleep overnight in the dormitory which, because of COVID social-distancing rules, has most of its bunkbeds blocked off.

The day I arrived at KBI, about a hundred migrants who have been staying in Nogales, Sonora, received meals, minor medical attention, showers, legal assistance, and kindness from staff and volunteers. Overwhelmingly, these families had hoped to file asylum claims, but were expelled from the United States without their claims being registered and with no timeline to return to make their claim. Another 34 migrants were new arrivals who had yet to attempt to cross into the United States.

What I saw inside KBI’s walls, and walking to and from the border crossing, was not quite what I expected after seeing pictures on TV these last few weeks. Contrary to the image former President Trump recently painted on Fox News of migrants “bringing violence to our country” and “destroying our country,” the men and women I saw at KBI were, to a person, people I would be happy to invite into my home. They weren’t threatening. Most were in family groups, with children who seemed happy despite their circumstances, their mothers watching over them carefully, some with fathers nearby. The single men present looked like workers you’d see at Home Depot any morning of the week. What amazed me was how these migrants had been able to maintain their dignity on what must have been a grueling journey—Guatemala City is more than two thousand miles from Nogales.

As I was leaving the center, I saw that not everyone arrived safely: A young mother cradling her unconscious toddler looked on as paramedics took the child’s temperature before loading her into an ambulance for the nearest hospital. I left before learning whether it was heat stroke or something else. Maybe COVID. The center has no access to testing, so new arrivals must quarantine from those who have been there awhile. COVID has made caring for migrants even harder than it was 18 months ago. But everyone wore masks, and hand-sanitizing stations were located throughout the building.

The next few months will prove more challenging as the number of migrants rises—as it does each spring—just as the temperatures of the desert become life-threateningly high. In March, Customs and Border Protection (CBP) apprehended some 172,331 migrants, the highest number since 2000. Of these, 53,782 were in family units and 18,890 were unaccompanied children, the highest on record. The implication of these numbers on Fox News and in other right-wing media is that the country is being flooded with unauthorized migrants, but for the most part, the adults in this group don’t remain in the United States. Instead, they’re processed and turned back to end up in places like KBI or in ad hoc migrant camps in Mexico—though Mexico has ended its formal acceptance of so-called “wait in Mexico” asylum seekers.

Many who are turned away will try to cross again—which inflates the numbers with recidivists, mostly single men, who try over and over to make it into the United States. A minority will succeed—but we won’t know how many until we begin to compare the estimated population of unauthorized immigrants present in 2020 with newer estimates that include the duration that individuals have been living here. According to one analysis of data from 2018, some 60 percent of such persons have lived here more than 10 years, including 14 percent who have been here for two decades or more.

Of course, the images that continue to haunt are those of children who have made the trek north without their parents and now wait in CBP custody until the Office of Refugee Resettlement (ORR) can place them with family members or in foster homes. Surveillance film of the border wall in the New Mexican desert captured last week depicts the extreme danger that many children face: Coyotes dropped two toddlers, ages 3 and 5, over the wall, where they were lucky to be rescued by CBP on the American side of the fence. Coyotes like these bring most of the children (most of the rest come with family members), some charging families money they often must borrow at usurious rates. In 2014, during the largest surge of unaccompanied minors, the Congressional Research Service found that some children were trafficked and forced into sex work by smugglers. Other children make the trip in the company of older kids, mostly teenagers, who themselves hope to win asylum in America.

What parent would risk sending a child thousands of miles, often on foot, through crime-ridden territory with an uncertain outcome? Only those who feel the chances of survival at home are worse. More than three-fourths of the children who arrive have family living in the United States, including about 40 percent who have a parent already here. If their parents had legal status, they could apply to bring their children legally—but they don’t, thanks to two decades of congressional dithering. Faced with a choice between leaving their children to face starvation in Guatemalan villages, or in southern Mexico where both drug cartels and anti-drug armed defense patrols are enlisting even 8-year-olds to join, many parents choose the unthinkable.

The lucky ones will make it into ORR custody and be united with family, a process that can take months—and years more before their asylum claims can be heard by an immigration court. The Biden administration is attempting to process more cases by allowing Department of Homeland Security officials to hear claims in addition to the 530 immigration judges who currently handle the million-plus-case backlog. But the first step is a public-education campaign to counteract the coyotes’ sales pitch that the border is now open to asylum seekers—which it is not. The president has told would-be migrants, “Don’t come over . . . don’t leave your town or city or community.”

When I asked my guide at KBI what will happen to the families I saw there, she told me many will try to cross again. Those who don’t will end up returning home, often borrowing more money to pay the bus fare south. She also told me of a family that left Nogales to return home to Guerrero, Mexico, last year. Three generations had come north seeking asylum, only to be sent back to the Mexican side of the border with no chance to make their asylum claim. Eventually, the couple left their parents and children to return to Guerrero, where they were both murdered by the local gang—the exact fate they had hoped to escape.

No wonder they keep coming.