Our Civil War Was Even Bigger Than You Think

Alan Taylor’s case for understanding it as a continental conflict.

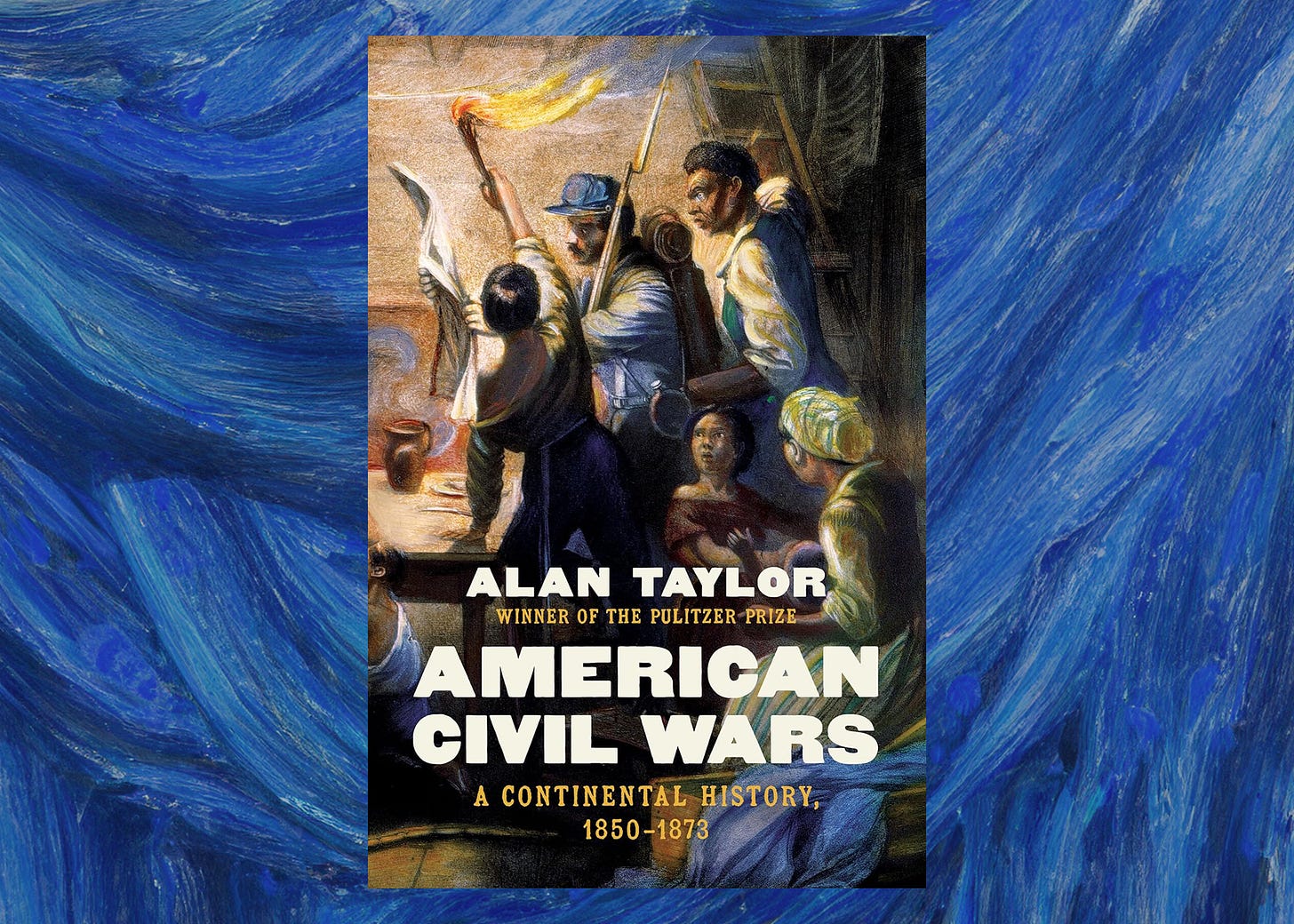

American Civil Wars

A Continental History, 1850–1873

by Alan Taylor

W.W. Norton, 534 pp., $39.99

IN THE MID-NINETEENTH CENTURY, across a swath of North America, a new nation cracked apart, unleashing waves of bloodshed that left no state untouched. Guerrillas strafed the countryside, while competing armies circled one another, clashing over a country’s destiny. Rattled by the burst of bloodshed, some politicians became convinced that the only solution to dissolution was something the American Founding Fathers had learned nearly a century previously: unification, and the birth of a new nation.

For American audiences, the story is a familiar one, following as it does the contours of the U.S. Civil War. But as Pulitzer Prize-winner Alan Taylor writes in American Civil Wars, this story—of fratricidal fighting, and of politicians carving a new nation out of nominally disparate polities—was not limited to the United States or its Confederate secessionists alone. These disasters and dreams rippled across the North American continent, rending Mexico apart and stitching Canada together at the same time. The story of the mid-nineteenth century, which we Americans usually think of as a tale of our own country’s fracture and eventual rebirth, is better understood as an entire remolding of North America writ large—and one in which the Civil War plays a far more continental, and even global, role than previously understood.

Taylor’s core argument is a compelling, and ultimately convincing, one. It builds upon a spate of other works that also sought to broaden the aperture of the U.S. Civil War beyond Gettysburg and Georgia, Shreveport and the Shenandoah Valley. There was, for instance, Megan Kate Nelson’s acclaimed The Three-Cornered War (2020), refocusing on the war’s Western theater, navigating all the bloodshed resulting from the Confederate thrust to the Pacific. There was also Don Doyle’s The Cause of All Nations (2014), which placed the Civil War in a transatlantic context, as part of a broader fight of liberty and republicanism against the forces of reactionary revanche. These books not only recentered the role and future of the American West as a casus belli for the war itself, but they’ve also restored the Americans’ war against the treasonous Confederates as a concurrent inspiration for others pushing for republicanism elsewhere, most especially in Europe.

It’s into this revisionist stream that Taylor has launched the latest—and, at over five hundred pages, bulkiest—effort. Taylor is unusually well qualified for a project of this continental scope; his widely praised previous books, from his examination of the American Revolution to the rise of populist forces under figures like Andrew Jackson, have sought to expand our notions of the American story—or, as it were, American stories. There’s a reason several of Taylor’s previous books are called things like American Revolutions and American Republics; as Taylor explains, “the plural titles convey a core attempt to see our history as continental rather than simply the isolated story of one nation.” In a sense, Taylor has spent much of his career inverting the famous American slogan of E pluribus unum—“out of many, one.” As Taylor ably argues, sometimes, out of many is simply many more.

SO IT IS WITH AMERICAN CIVIL WARS. As Taylor writes, the kind of state fracture and state consolidation we associate with the Civil War were not limited to the United States.

Look, as Taylor points us, to Mexico. That country’s fractious politics, laced for decades with rotating strongmen and beleaguered liberals, finally collapsed by mid-century into outright civil war, with ousted figures like Benito Juárez escaping a claque of competing generals, all while trying to triangulate around local caudillos who just want to keep their revenue spigots open. Into the breach stepped a European empire, looking to reclaim its own piece of North America. While the United States was mired in its own civil war, Napoleon III launched an invasion of Mexico, appointing the waifish, waffling Maximilian I as the new head of his Mexican satrapy. While these French-backed forces never controlled much beyond the corridor between Veracruz and Mexico City—and while few Mexicans ever recognized the legitimacy of this French colonization effort—Maximilian’s reign only worsened Mexico’s bloodletting.

Eventually, however, realizing that his Mexican misadventures cost him much more than he’d ever gain, Napoleon III cut Maximilian loose. Suddenly facing pushback from both liberals and locals, Maximilian’s remaining support quickly melted away. (It didn’t help that Maximilian, as Taylor points out, “neglected his . . . duties to travel the countryside, collecting birds, butterflies, flowers, and antiquities.”) Juárez soon returned to power, and Mexican republicanism, just like American republicanism, was restored—even as, in the distance, a Mexican general named Porfirio Díaz started to recognize his own opportunity in the instability.

Taylor looks to the north as well. While British Canada never suffered anything like the slaughter of places like Puebla or Antietam, it still saw the kinds of sociopolitical cleavages like those of the United States and Mexico. For years, British Canada had enjoyed equal parity, in terms of both power and population, among Francophone Catholics in Quebec and Anglophone Protestants elsewhere. But an immigration upsurge in the mid-nineteenth century tilted things firmly in favor of English speakers. Similar to the Confederates watching their own demographics swamped by other, non-slave American states, Quebecers suddenly realized their own political futures were slipping from their control—and that, in another parallel to the Confederates, it was time to reformulate the entire Canadian arrangement, or potentially even detonate Canada wholesale.

Into the breach stepped political figures like John A. Macdonald. Largely unknown outside of Canada, Macdonald was one of the savants of the era—despite (or perhaps because of?) his alcoholism. (Taylor relates that when Macdonald and a government colleague were both denounced for their public drinking, “Macdonald allegedly took his friend aside: ‘Look here McGee, this Cabinet can’t afford two drunkards, and I’m not quitting.’”) Not only did Macdonald manage to soothe the political fractures suddenly threatening to destabilize Canada, but he managed to do so while simultaneously balancing waning British interest and incorporating new polities in places like the Maritime Provinces and British Columbia. Thanks to Macdonald’s savvy, the threats of a roiling rupture receded—and a new federation, comprising modern Canada, emerged.

ON THEIR OWN, the parallel tales of Mexican disintegration and Canadian confederation would be fascinating geographical bookends to the story of the American Civil War. But Taylor, in his book’s greatest strength, doesn’t simply rehash the stories of these neighboring nations, but stitches them to the American saga.

Indeed, as Taylor outlines, it is the interplay of these jostling forces within Mexico, the United States, and Canada that truly makes the era, and his book, a continental swirl. All of these developments reflected and refracted one another, these nations all adapting and adjusting based on what was taking place in the others.

All sides in the Mexican civil war, for instance, looked northward for both inspiration and succor. Liberals like Juárez looked especially to Lincoln for backing, including for armed intervention, while both Maximilian and regional caudillos looked to Confederates for both diplomatic and financial support. All the while, Paris shied from formal recognition of the Confederacy—if only because such recognition would result in the kind of anti-French American intervention Mexican liberals hoped for.

In Ottawa, meanwhile, the fractiousness that defined Canadian politics faded fast in the face of a restored American Union supposedly looking to annex Canada. Such threats never extended beyond the realm of rhetoric—but a resurgent United States, suddenly solving its domestic issues and looking to expend its expansionist energies elsewhere, was enough to convince Canadian rivals to put their disagreements behind them. Unite, the Canadians realized, or face the potential perils of an American intervention none of them wanted.

Unsurprisingly, the United States was affected by more of these external developments than the others—if only because it is sandwiched between the two other countries. French interventionism in Mexico convinced on-the-fence Americans of the need to support the Union, for fear of potential European reconquest of their own American states. Meanwhile, debate in the United States about potential annexation of Canada helped restore a semblance of unity to America’s political class—if only, as folks like Secretary of State William Seward saw it, as a means of uniting Americans in a shared venture once more.

Seward had to settle for annexing Alaska alone. (This purchase was made possible in part because the tsarist government in Russia was convinced that American annexation of Canada was inevitable, and that St. Petersburg might as well get something in return for offloading a distant province before American annexationists forced them out later.) And both Mexico and Canada remained—at least for the most part—free from the kind of American interventionism that came to define relations with further-flung regions, far beyond North America.

IF THERE IS A FAULT in American Civil Wars, it’s not in the framing but in the balance of the stories. The book ultimately ends up as an uneven effort, undone by Taylor’s overwhelming focus on the American Civil War itself. That story is, of course, the key to unlocking much of the era’s continental history—but the details of the war itself are, to put it mildly, already well-trod. Do we really need another rehashing of the lineup of generals Lincoln sorted through, or of the specific set pieces in Sherman’s march?

Perhaps Taylor’s background as an Americanist made such an lopsided focus on the American Civil War an inevitability. But for the book to carry so much minutiae about that war, it needed to have been twice as long, to give equal shrift to developments in Mexico or Canada—or alternatively, the U.S. sections could have been hacked down, making a tauter read. Alas, the book’s bloat will prevent it from attaining the status of other modern classics on the U.S. Civil War, such as James McPherson’s Battle Cry of Freedom or Stephanie McCurry’s Confederate Reckoning.

Still, Taylor’s new book accomplishes something crucial that its predecessors didn’t. The American Civil War didn’t belong to Americans alone, and the saga of dissolution and reconstruction in the mid-nineteenth century didn’t belong to America alone. It was also part of a broader North American story—and all of it took place in an era that birthed not only a renewed American nation, but an entire continent as we know it.