Ozempic and Your Community

How GLP-1 therapies could help build a healthier, more productive workforce—and what that would mean for how we live together.

AS HOLIDAY TREATS GIVE WAY TO NEW YEAR’S RESOLUTIONS, the names of GLP-1 weight-loss drugs like Ozempic and Wegovy will be on millions of lips this January—in addition to any leftover fruitcake, eggnog, cookies, and latkes. But the benefits of these drugs aren’t limited to what they can do for an individual’s health.

Recent analysis of GLP-1 weight-loss therapies by Citi and Goldman Sachs uncovered an interesting and underdiscussed benefit: increased worker productivity. Widely deployed, these drugs could raise labor productivity by up to 0.5 percent. That number may not sound like much, but such an acceleration would be a dramatic boost to the economy of the United States and the health of its citizens. In low-income and disadvantaged communities and regions, where obesity rates are often the highest and rates of work the lowest, access to these medications might be transformational.

One of the paradoxes of our age is that the more economically disadvantaged you are, the more likely you will be overweight or obese. For millennia, human beings were locked in subsistence economies, not always sure when or from where the next meal was coming. This environment made high-calorie and high-sugar foods especially prized.

But in an era of food abundance, our genetically encoded calorie-seeking behavior is no longer a survival benefit. Quite the opposite, in fact. With abundant food, often laced with saturated fats and processed sugar, chasing calories has become life-shortening behavior. Overeating and eating unhealthy foods leads to obesity, which cascades into a wide range of our most serious health problems—heart disease, diabetes, kidney failure (all related to one another), cancer, and dementia. This cluster of obesity-driven conditions shortens lifespans and lessens well-being, while simultaneously draining our healthcare system.

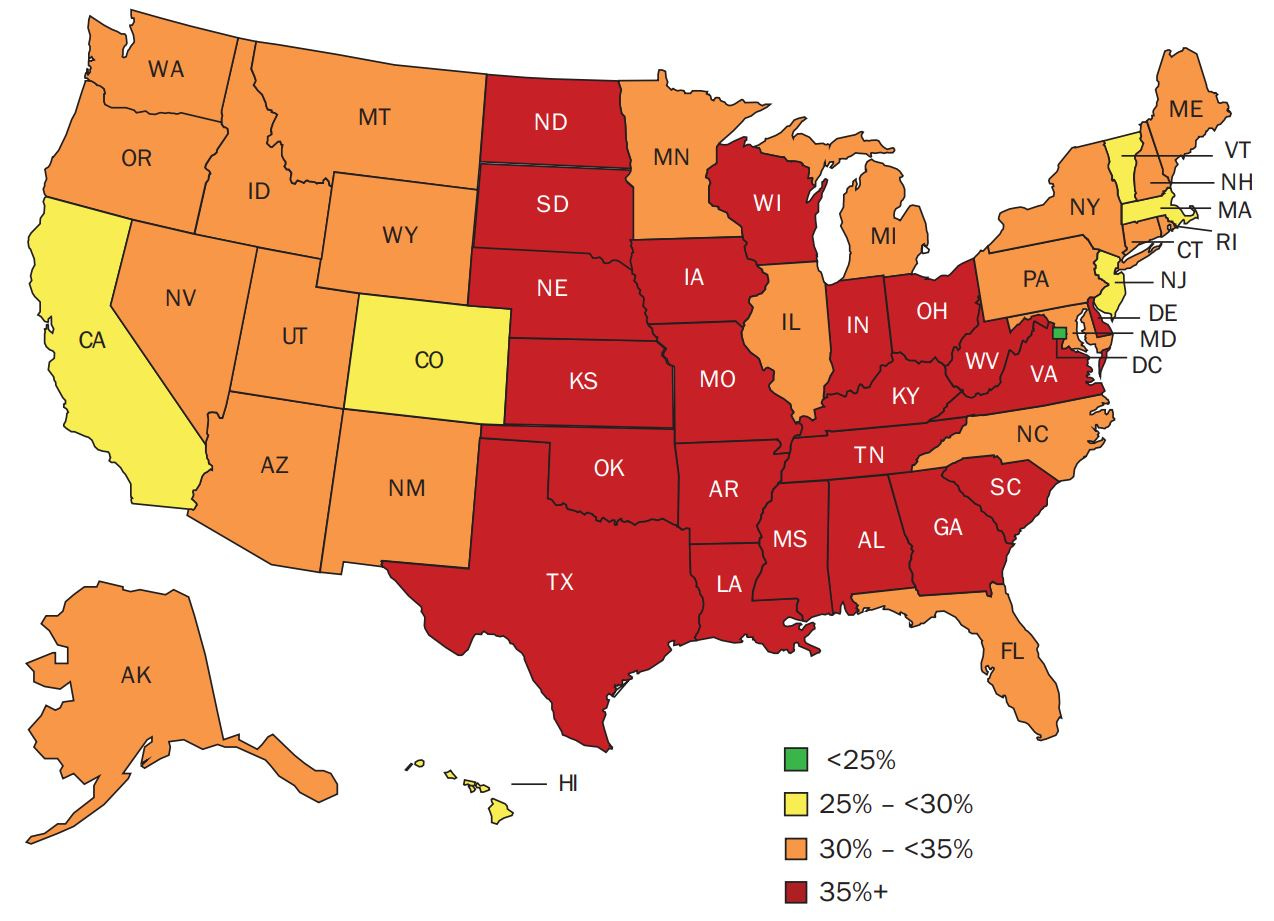

Obesity prevalence by state, 2022

Federal and state governments have in the past focused most anti-obesity efforts on behavior modification, the same thing doctors recommend for everyone: diet and exercise. Outcomes for many of these programs have shown positive but short-lived effects. Any frequent dieter who has seen their weight yoyo has faced a similar and discouraging problem: The body “remembers” its prior weight, interprets weight loss as starvation, and seeks to regain the pounds. A 2016 study in the journal Obesity found that among participants in The Biggest Loser reality TV series, virtually all participants in the show’s extreme diet and exercise program regained a significant portion of the weight they lost, and some exceeded the weight at which they started. GLP-1s, on the other hand, target the physical mechanisms of overeating rather than treating it exclusively as a problem of willpower or behavior modification, offering obese people a way to lose weight and keep it off.

The underlying theory of the Goldman Sachs estimates of GLP-1 economic impact is simple: By reducing the disease burden in the population, worker productivity will increase significantly. Less illness equals healthier people and more work, an especially important effect for populations in which employment levels are persistently below average and obesity rates above average. Minority women are much more likely to be obese than white women, according to CDC health statistics. The rate of obesity for white women is 39.8 percent compared to 56.9 percent for black women and 43.7 for Hispanic women. Additionally, women with lower incomes experience higher rates of obesity, whereas for men, obesity rates are similar across income levels. Male obesity seems relatively similar across races with low-income males more exposed than higher-income males.

Obesity and its related health conditions also show signs of being intergenerational for genetic, epigenetic, and cultural reasons. In other words, obesity isn’t just a problem for individuals; it is heritable and has community-wide effects on health, well-being, and very likely employment. As such, it should be addressed as a community-based, intergenerational, and employment challenge. We could be treating fewer cases of heart disease, cancer, and dementia if we did a better job of interrupting the eating behaviors that contribute to them. This might be the right moment to try a community-based GLP-1 experiment. Bowling Green, Kentucky, now known as the Ozempic capital of the country, has something of a natural experiment going on as a large portion of the city is seeking GLP-1 treatment.

Over the past few years, the federal government has launched a number of new workforce-related initiatives that could benefit from voluntary obesity-reduction wraparound interventions. Under the CHIPS and Science Act, Inflation Reduction Act, Build Back Better Act, and American Rescue Plan, the federal government is making significant investments in workforce development programs aimed at increasing access to training, skills, and employment in disadvantaged areas of the country. Many of these projects are in regions with high levels of joblessness and obesity. A voluntary wellness program that incorporates diet, exercise, and access to GLP-1 medications seems like a good fit for addressing chronic and endemic obesity while also building technical skills and placing participants in jobs.

Such an effort would likely require additional resources. In some cases, state Medicaid programs may be able to help defray costs. However, without insurance, GLP-1 treatments can run to $1,000 per month or more, meaning they would likely need support from outside these workforce-related grants. Moreover, obesity is a progressive disease that doesn’t completely go away with drug therapy, likely requiring ongoing access to medication and long-term financial commitments. As the drugs become cheaper and more plentiful—including through the development of new compounds—prices should decline. In the meantime, philanthropic efforts could fill the gap.

The potential payoffs of widespread obesity reduction are great. The savings from reduced health-care costs for chronic diseases would likely offset much of the costs of the intervention, not to mention the harder-to-measure but substantial psychosocial improvements for individuals and families. Meanwhile, communities would benefit from a healthier workforce more capable of gaining and keeping jobs. As people consider weight loss for themselves this season, let’s take this opportunity to think about making these treatments widely accessible—so in the spirit of “new year, new you” we can hope for new communities, too.