Pain Seeking Understanding

Two recent memoirs put the authors’ ongoing experiences of personal suffering in the service of more complete views of the world.

The Sound of Undoing

A Memoir in Essays

by Paige Towers

Nebraska, 210 pp., $21.95

Losing Music

A Memoir

by John Cotter

Milkweed, 320 pp., $26

CURIOSITY AND LEISURE FORMED the matrix of the modern essay, but pain was close behind. Montaigne was in his mid-forties when he became, as he put it, “acquainted with the kidney stone through the liberality of the years.” The stones drove him to baths all over Western Europe, to purgatives, enemas, and bloodletting. He was chagrined to find himself investigating the contents of his chamber pot, measuring what he voided against what he’d drunk. It was a family disease; it killed his father. “It was precisely,” he said, “of all the accidents of old age, the one I feared the most.” He thought it might be better to die, at first. Yet “I am already growing reconciled to this colicky life,” he reported after living it for eighteen months, “I find in it food for consolation and hope.” The ailment sharpened the perspective that came to characterize the Essays—delight in physicality, mistrust of those who would leave it behind (“these transcendental humors frighten me”), loving laughter at human frailty. “We seek other conditions because we do not understand the use of our own,” he wrote on the last page of his book, and the form he named was his attempt to understand his, healthy or sick. Two new memoirs take up this attempt to live the examined life amid ongoing personal suffering. Their authors seek to understand their own conditions and consider whether there might be any use in them.

Paige Towers’s The Sound of Undoing is a collection of short lyric essays framed by Towers’s hypersensitivity to sound, which has gifted her with a deep attentiveness to the world while also making modern life into something unbearably loud. As the essays accrete, several stories emerge: Towers’s complex relationship with her family; a prolonged period of depression, isolation, and self-medication; the comforts and challenges of marriage.

John Cotter’s Losing Music also uses hearing trouble to bring a life into focus, but from the side of silence rather than noise. Cotter has Ménière’s disease, a poorly understood cluster of symptoms that manifests for him in intermittent but deepening hearing loss and debilitating, days-long spells of vertigo. The book plots his relationship to the disease: his discovery of it, its effect on his life and work, his increasing despair, and then, gradually, his acquiescence to a new life.

It is satisfying to report that both authors explore their conditions through formal and stylistic choices. Towers presents the reader with the cacophony she hears, building each essay around a different sound, often onomatopoeized and examined in all its contours. In some chapters the central sound bears directly on the subject at hand (gunfire in a chapter on urban violence), in others it serves as metonymy (scissors and a falling-out with her sister), in still others it stands in a more associative relation to the essay (birdsong in a heartfelt if overclocked paean to her husband). The technique defamiliarizes Towers’s life just enough that she is able to anatomize it in greater depth than an ordinary narrative would allow, though the more tenuous connections can creak under the weight of the conceit they are asked to bear.

Losing Music, on the other hand, is full of silences and conversational lacunae—hearing aids cannot prioritize sounds as the ear can; your table partner’s question can drown in the general roar of the restaurant. Fittingly, one of Cotter’s principal techniques is leaving things unsaid. He relates his love of Shakespeare and punctuates a chapter with quotations. In the following chapter he struggles with suicidal thoughts. Does he cite Shakespeare’s best-known monologue, the one about suicide? He doesn’t have to. The reader has been suitably primed; we supply it on our own. In this way, he places great trust in his audience; we become responsible for part of the effect, and that responsibility invests us more deeply in his story. It’s a technique from theater: Put a chair on a bare stage and the audience provides the whole room. (It’s no coincidence Cotter has directed and acted in plays for years.) The technique also evinces the confidence Cotter has in his own writing. Here is a book about deafness and music where Beethoven is mentioned exactly once, and almost 200 pages in—there are too many other things to talk about first.

Though we learn quite a bit about the way Towers’s acute hearing shapes the texture of her life, she has not written an illness memoir; she makes no attempt at diagnosis or cure. Resigned to her estate, she tries to understand the phenomenology of her hearing. In this she is not unlike Montaigne pondering his diary of symptoms experienced (“by glancing through these little notes, disconnected like the Sibyl’s leaves, I never fail to find grounds for comfort in some favorable prognostic from past experience”). The most obvious conclusion is that she needs peace and quiet to thrive. But her book constantly questions that need and attempts to tabulate its cost. The silence between her and her sister, for example, is a tragedy. The silence of God nags at her; she doubts her doubt (“maybe I am just fighting God”). Towers’s habit of watching TV with one finger on the mute button is an inheritance from her father, who at times tyrannized their family with his own need for quiet. She doesn’t want to burden her loved ones in the same way, but she swerves from straightforward condemnation: “When his anxiety isn’t at the wheel, my father is one of the most wonderful people you’ll ever be fortunate enough to know.” Instead of desiring real or relational silence—“you just have to cut toxic people out of your life,” she is advised—she insists, through discomfort, on maintaining unity among the disparate parts of her life, and will not let them go to spare herself pain.

Those hesitations lead her to the political implications of silence. Dampening the literal noise, she posits, could mean abdicating social responsibility, tuning out instead of easing suffering or organizing to end it. In two late chapters, she pairs a discussion of urban noise pollution with accounts of violence in Milwaukee. Why not leave? Not everyone can. “Peace and quiet,” she says, “are privileges that go to the highest bidder.” It is perhaps, in 2023, the expected move to make, and Towers’s juxtapositions can produce the odd flattening effect such lyric contrasts always risk. There is a constant shifting of figure and ground—the political problem is always in danger of becoming a mere metaphor for the more abstract or personal one. What animates The Sound of Undoing, though, is the humanist’s interest in nuance and distinctions, and an admirable suspicion of the things that palliate the noise of modern life.

LETTING GO IS PRECISELY the task for Cotter. Not of other people, of course—his friends, his mother, and his wife remain central to his life—but of himself: his conception of who he was before his hearing began to go. Interventions from doctors, pronouncements from specialists, and even a week at the Mayo Clinic prove only that his condition is intractable, and that it will get worse. (Like Montaigne, he comes to regard doctors with skepticism and some disrespect.) He accepts there will be no moment of deliverance, either through medicine or sudden self-transcendence. At one point he describes meditation: “I noticed myself grinding my teeth. I’d been in my head, escaping the noise. But it’s a mistake to try to find the other side of it. Instead I was intended to . . . to what?” To accommodate, it seems, is the answer—a process that happens, maddeningly, at the inflexible rate of one day at a time. Cotter doesn’t tell us what it feels like because it rarely if ever feels like anything. You can’t catch it happening, but you can take its measure against memory, when people or places are revisited. You return to the same old river and find you and the water have both changed.

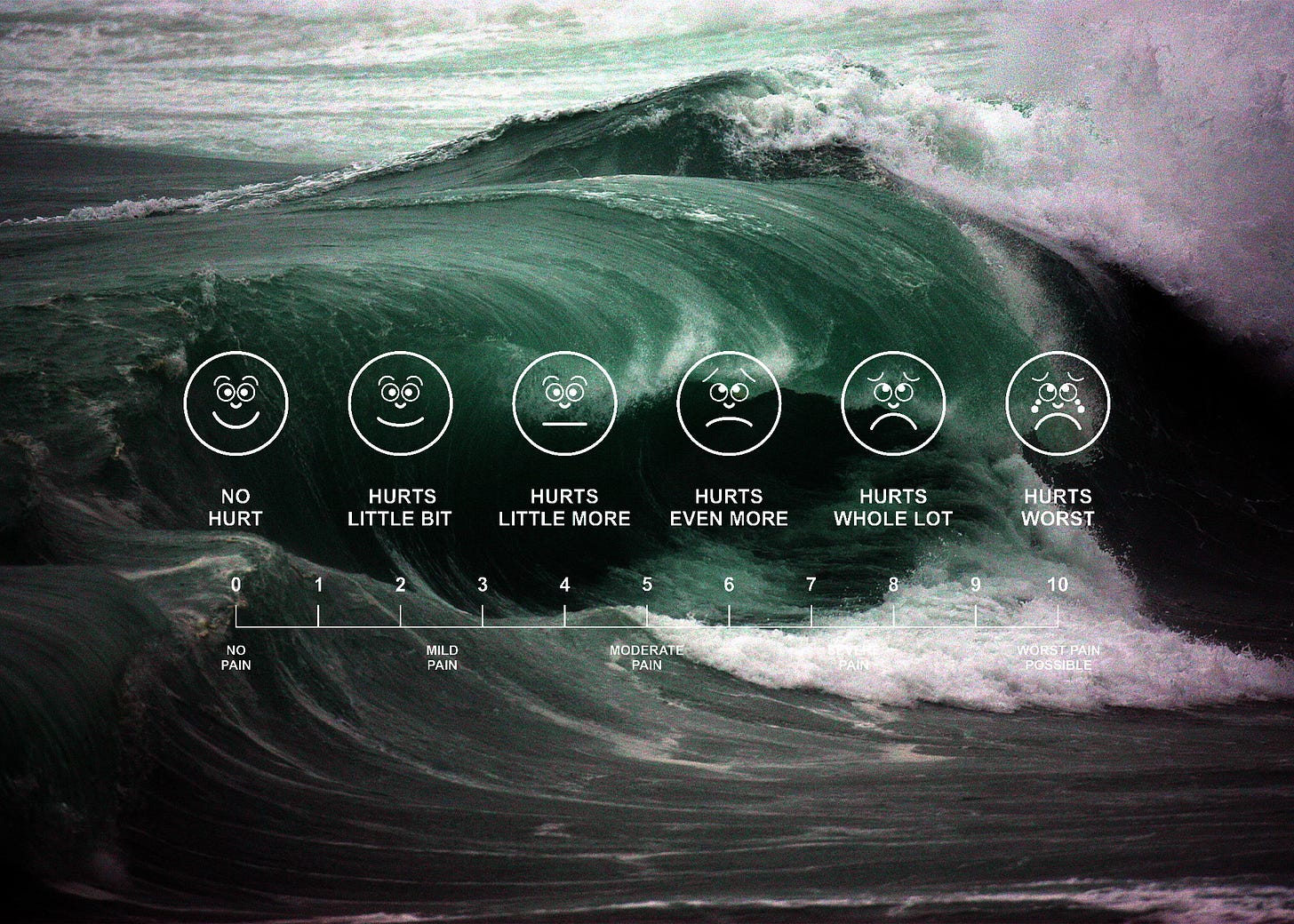

The second half of Losing Music gives us some of those moments. New experiences are arranged in a loose chiasmus with the book’s first part to provide evidence of Cotter’s transformation. He works as a live-in teacher at an old cavalry fort–turned–homeless shelter outside Denver, and the precarity and suffering of its residents give him a sense of proportion while also opening certain possibilities: “Of the language of pain, although I possessed no fluency, I could understand and speak a little . . . I would know how to listen.” Pain, so isolating and subjective, becomes the warrant for connection. He finds a fellow traveler in Jonathan Swift, who likely also suffered from Ménière’s, and sees his present and potential future in Swift’s irritability, loneliness, and bitter humor. Far from the kind of glib biographical criticism that reduces an artist’s work to the conditions under which it was produced, Cotter’s reading of Swift is extremely sensitive thanks to his unique qualifications—a great gift to the cantankerous old Dean, understood at last. Solidarity is not an experience restricted to the living.

Cotter finds new ways to deal with restaurants, work, sex, conversation. (“Often I nod and pretend. It’s necessary to pretend.”) The mind is plastic: “You train yourself; you wouldn’t think any more to do things otherwise.” He contemplates the arbitrariness of fate, the relative lack of control he has—that any of us have—over events, and the persistence of choice in spite of it. “I get through days by understanding that, when the worst happens, if it happens . . . such a thing will be another life. Not a posthumous life, but something that changes me into a person I can’t see from here.” As Hamlet says to Horatio, “The readiness is all.”

In the last chapter of each book, both authors confess to carrying a knife around. For Towers it’s a protective measure; for Cotter it was a ready means to end his life (he is speaking in the past tense). It maps almost too perfectly onto their projects: The former is at odds with a seemingly hostile world, the latter with himself. Their books are records of putting the knife down. In both cases, doing so entails a reconciliation to certain stubborn, untranscendable material facts, and an acceptance of ongoing suffering. “The most barbarous of our maladies is to despise our being,” Montaigne said, meaning our bodies, including his poor stone-filled one. “With the occlusion of the body there is an anaesthesia of sensibilities,” suggests Guy Davenport, regarding Montaigne’s intimate relation to his ailment. Towers and Cotter, then, are wide awake, and their books, like Montaigne’s, make the bold and possibly offensive claim that some truths can be learned only by attending to pain. The discursive essay—the attempt to comprehend some dogged facet of the world from inside a particular, subjective mind—seems almost purpose-built for such truths, and these two books are therefore not just fine new entries in the tradition Montaigne inaugurated: They are very close to its heart.