Paying the Bill for the Pandemic-Related Unemployment Benefits

Congress used to finance additional unemployment benefits by raising federal unemployment taxes. Not anymore.

Congress has enacted the largest economic stimulus in history in response to the coronavirus pandemic, providing over $2 trillion in federal aid so far. That includes hundreds of billions of dollars for the now-expired $600-per-week federal unemployment bonus. But almost no attention has been paid to how those unemployment benefits are financed. Instead of using worker payroll taxes, Congress has tapped unprecedented amounts of federal general revenues, adding to the national debt at an alarming rate. And unlike Congresses of the past, current policymakers show no intention of ever repaying those funds. That ignores what previously was a common question that tempered Congress’s appetite for big benefit increases: How high will federal unemployment taxes have to rise to pay for expanded unemployment benefits?

Since its inception, the unemployment insurance (UI) program has been supported by a state and a federal payroll tax imposed on employers (though ultimately the cost of these taxes is borne by workers through lower wages and fewer job opportunities). The revenue from those taxes is credited to state and federal trust funds that are normally used to pay UI benefits.

But this time is different, both in the suddenness and depth of unemployment resulting from the pandemic and in the extraordinary federal benefits response. Another difference is that not a single dime of the federal UI trust funds has been used to support the cost of either federal unemployment bonuses or the Pandemic Unemployment Assistance (PUA) program. Instead, Congress tapped federal general revenues, which are typically used for welfare benefits, national security, and everything else aside from the mandatory spending on the nation’s “social insurance” system for workers.

The scale of general revenues flowing through the UI system is unprecedented. During five months through August 15, federal spending for the $600 bonuses totaled $260 billion, while spending on PUA benefits was $37 billion. That already exceeds federal unemployment benefit spending during the six-year response to the Great Recession. Extending current federal benefits into early 2021, as the House approved in May, would spend another $437 billion—coming almost entirely from general revenues. If Congress agrees to that, federal unemployment spending would total well over $700 billion, or more than 100 times the $7 billion in federal UI payroll tax revenue collected each year.

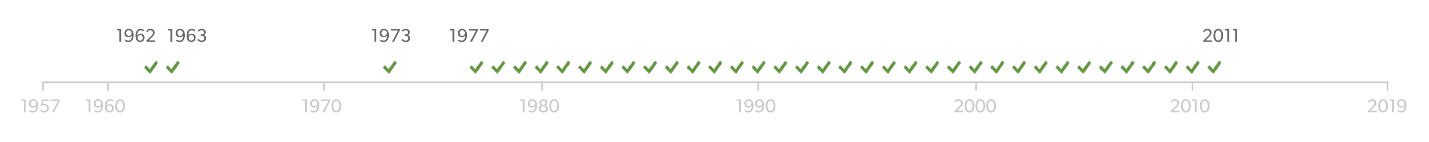

How will Congress pay for that? Its current approach is simply not to, adding these costs to the national debt. But that is contrary to historic norms of the UI system. Congress has tapped general revenues before to finance federal unemployment benefits when federal trust funds ran dry. But a federal unemployment surtax was often levied to finance those costs. The graphic below shows a surtax applied in 38 of the 63 years (that is, 60 percent of the years) since 1957 (the year when federal extended benefits were first provided):

Years when a federal unemployment surtax was in effect, 1957-present:

Congressional Research Service (https://fas.org/sgp/crs/misc/R44527.pdf)

If the current Congress followed this practice and levied a surtax to recoup general revenues projected to be spent on federal benefits through early 2021, today’s federal UI tax of typically $42 per worker per year would grow to $482—a 1,048 percent increase—and stay there for a decade. The federal UI tax rate would skyrocket from 0.6 percent to 6.6 percent, or more than double today’s Medicare tax rate (which is applied over a different wage base). That sharply elevated federal UI tax rate would be on top of state payroll tax hikes already coming to re-build state UI trust funds.

What are the chances of such a federal UI tax hike occurring? Almost nil, for several reasons. Few in Washington today think anything needs to be paid for, least of all stimulus spending in response to the pandemic. Using general revenues to finance social insurance benefits also has long lost any stigma. And the payroll tax hikes would be so huge both parties simply look the other way.

But, again, that leaves unasked the critical and previously routine question: How high will federal unemployment taxes rise to pay for additional federal unemployment benefits? In the past, knowing that increases in current benefits supported by non-UI funds had a downside—future payroll tax hikes—Congress exercised greater discipline. Now, a Congress unaccustomed even in ordinary times to thinking seriously about deficits feels no such restraint. Indeed, as Congress and the administration negotiate the next round of unemployment benefit increases, that prior restraint appears gone, probably forever.