Every Saturday I highlight three newsletters that are worth your time.

Most of what we do in Bulwark+ is only for our members, but this email will always be open to everyone.

Sign up to get on the list for this newsletter and for all of our free stuff. (There’s a lot of it.)

1. First, We Kill Twitter

I am very happy that Elon Musk owns Twitter because there’s a non-zero chance that he’ll wreck the platform.

Here is a true thing about Twitter, courtesy of Embedded, which is an excellent newsletter about tech:

The thought of logging onto Twitter and seeing nothing gives me a profound sense of calm . . . But this is puzzling, because Twitter is responsible for my whole career.

In 2015, journalists made up the largest category of Twitter’s verified users, and they were also the most active, too. I graduated from college right into the heyday of this incestual sweat lodge of a community. I was an aspiring writer with no connections of my own to digital media, and Twitter was my golden ticket.

From my dorm room in Ohio I followed the major and minor players on the website, from prolific journalists with prestigious bylines to young women who got famous for tweeting things like “i came, i saw, i dissociated.” I slinked into their replies, boldy @-ed them with my own musings, and, once I moved to New York, actually starting meeting them in person.

I got my first job toiling in the depths of a content mine, stood in the corners at digital media parties staring at my phone, and portrayed it all online like I was having the time of my life. Maintaining this social and professional facade was necessary for getting editors to respond to my emails, and having acquaintances slide into my DMs with opportunities whenever I got laid off.

This is why, despite all my complaining about the service, I’ve never just deleted my account. It’s why, even though I’ve stopped tweeting about everything else in my life, I still post whenever I write a new article. As a writer who hopes to keep being a writer, Twitter is pretty much the only lever I have to pull. It would, I insist to my friends, my family, and my therapist, be career suicide to log off.

That’s not an exaggeration. Twitter is like a mashed up Trimurti for journalists: It is simultaneously the creator, preserver, and destroyer of careers.

You can go from nothing to a full-time media gig based on the strength of your Twitter presence. When other media people want to know something about you, they look at your Twitter feed first—not your clips. And you can send out dozens of bad tweets without any consequences. But if one of them randomly turns you into the site’s main character for a day, you can lose your job.

It’s messed up.

And I don’t mean that in as a matter of personal unpleasantness: It’s messed up at a systematic level, because Twitter established a nihilistic set of incentives for the media, which in turn helped create a toxic public square for everyone else.

For years I’ve tried arguing my friends off of Twitter. I’ve appealed to their intellects, their decency, the fate of their eternal souls, and their time management compulsions. It’s never worked. I have not talked a single person off of Twitter.

That’s because the incentives are real. If you’re a writer and you don’t do Twitter, you might as well not exist. And because the incentives are real and powerful, we were never going to kill Twitter by convincing people to leave the platform. But maybe Elon will kill Twitter for us by accident.

Back to Embedded:

This might be a good thing for journalism itself. The accessibility and immediacy of Twitter means writers, myself included, can erroneously conflate the majority opinion of Twitter users with the majority opinion of actual society. But, as Pew Research Center has concluded time and time again, a minority of extremely active Twitter users produce the overwhelming majority of all tweets made by U.S. adults.

Read the whole thing and subscribe.

Talking about this with a friend last week, she said that even if Twitter dies, something else will replace it.

That’s not necessarily true. MySpace was never really replaced by Facebook. And when Facebook dies, TikTok won’t really replace it, either. New platforms create different niches. And looking toward to our TikTok future, I don’t think it’s as amenable to media collectivization as Twitter was.

The future of Twitter seems more likely to be a return to something like the blogosphere—which is what Substack is, more or less. Twitter killed the blogosphere and its success prevented Medium from replacing it. Substack may have come along at precisely the right time to use Twitter to fuel its initial growth—and then become a default home for media should Twitter go nova.

And that would be good—because the incentives for a longform, non-networked, slow communication platform are much less pernicious than the networked immediacy of Twitter.

In theory Musk could “fix,” Twitter, too. By which I mean: Evolve the platform so that it becomes less toxic to society.

Doing so would probably mean going backwards. It would almost certainly involve down-building and dismantling network effects; taking steps to put limiters on virality and cut down on the number of users.

It would also involve a lot more content moderation. And not just the cancel-culture kind that most people fixate on, which tries to keep out racists and disinformation and whatnot. Much more important is the kind of moderation that keeps bots and spam to a very low level and helps figure out if an account has been hacked and if so, how to restore it.

But at the risk of being crass: The size of the debt burden Musk has assumed makes such an evolution impossible.

He’s going to need to cut spending (meaning: employees) by something in the neighborhood of half. He will simultaneously need to pursue aggressive, immediate revenue growth (meaning: user growth). In short, Musk’s financial incentives—dictated to him by the hilariously bad deal he negotiated—mean that he probably has to make Twitter even worse.

Any chance that he could have improved the platform went out the window when ZIRP disappeared and the deal exploded in his face. The size and character of Musk’s debt load will probably compel Musk to make Twitter a worse product, no matter how much he loves humanity.

Maybe it’ll get so bad that he kills it.

A boy can dream.

2. Wild West

Speaking of tech moguls getting slapped: Last week Washington State fined Meta (Facebook) $24.6 million.

Before there was the case of State of Washington v. Meta, there was a long-running state agency investigation into Facebook’s failure to comply with Washington’s political ad disclosure law. That investigation was conducted by the Washington State Public Disclosure Commission (PDC), which is tasked with enforcing state campaign finance law and has its own power to issue fines.

But in February 2020, it came to light that the PDC’s leadership was recommending a pretty sweet deal for Facebook. Although Facebook had, at that point, failed to disclose required information about hundreds of political ads targeting Washington State’s elections, the company, under the 2020 deal proposed by the PDC, would have been able to settle the matter by paying a $75,000 fine, admitting no guilt, and making no binding promises to follow Washington State law going forward.

Experts called the PDC’s proposed settlement “dangerous” and “troubling.” The former chair of the board of commissioners that oversees the agency, Anne Levinson, said the proposed settlement raised “significant concerns” and was not something she would have voted to accept. And when the PDC’s active commissioners voted on the matter, they unanimously rejected the settlement that had been recommended by Facebook and the PDC’s executive director, Peter Frey Lavallee. Instead, the Commissioners referred the matter to Attorney General Ferguson.

That quickly led to Ferguson filing suit against Facebook. After the company’s name-change, Ferguson’s case became State of Washington v. Meta.

Read the whole thing. The entire history of this case is fascinating and this occasional newsletter is worth your time, if you like tech and law questions.

3. Love and Treason

Natalia Antonova noticed something in the stories about the couple from Maryland who were arrested for spying for the Russians last month:

Major Jamie Lee Henry and his wife, Anna Gabrielian, met with an undercover FBI agent who they thought worked for the Russian government and tried to pass sensitive information along in order to aid Russia’s barbaric war. . . .

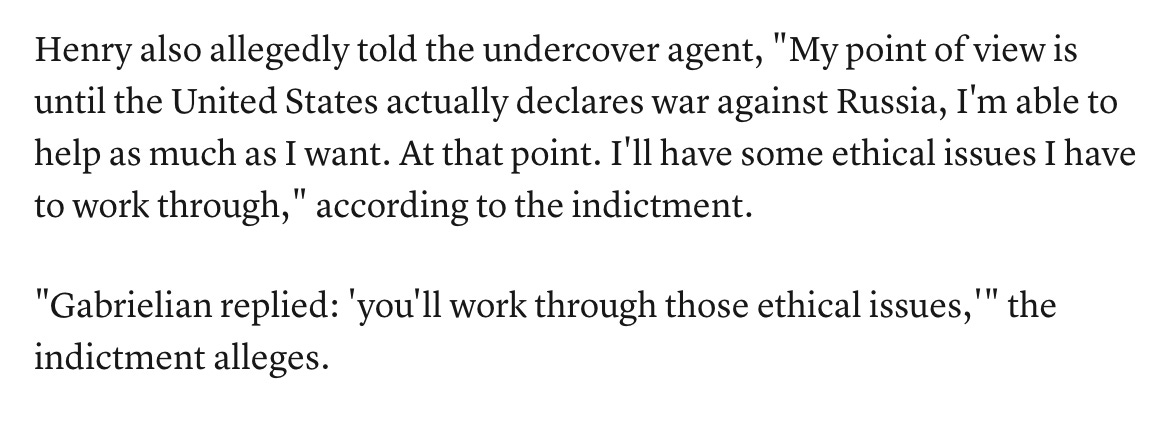

There is one specific detail from the indictment that these journalists zeroed in on. It’s about Henry’s hesitation when speaking to the person he thought worked for Russia. This is a screenshot of that exchange:

So Henry is worried that if the U.S. actually fights Russia directly, he will have a problem. His wife interjects and says that he will solve that problem. Notice the power dynamic here? She’s saying this in front of their supposed “Russian contact.” She is not pulling her husband aside to whisper in his ear. She is putting him on the spot.

Read the whole thing and subscribe. Antonova takes a pretty sensible view of treason:

Russians hate traitors. For example, do you think they love Snowden? He may have been useful to them once, but now they mostly regard him as a curiosity at best. An unhappy curiosity, when you really dig into it. He’s not feted. He’s closely watched.

Because, once a traitor — always a traitor. It’s the only bit of Russian logic that has made any sense to me.

If you find this newsletter valuable, please share it with a friend. And if you want to get this every week, sign up below. It’s free.

I have no real insight as to how much effort is required to research, collate, and corroborate all the possible newsletters in the world into three pertinent suggestions each week. I suspect the process is quite time consuming. So my comment is just to say thank you to JVL and the Bulwark staff for providing the weekly newsletter selections. They make me smarter.

Don't use Twitter, rarely read Twitter, unless it's someone whose views I specifically care about, like a real expert on Russia or military affairs. Twitter is bad, but I think it will be replaced, unfortunately. We had Vine, (which Twitter owned, but shut down), and it was replaced by TikTok. Twitter's misuse and distortion illustrates three points I'll focus on.

1. The thirst for data: People, people in politics and journalism especially, are desperately hungry to know what people think for obvious reasons. Twitter provides that, even if it's distorting and basically bad data. It's better than nothing, goes the thinking (which is wrong, because "I don't know what people think" is less harmful than misunderstanding what people think.)

2. Low journalistic standards: Even if it's bad, it's available. Journalists are desperate for sources, and Twitter is available for instant hot takes. Polls don't exist on every issue that just happened. Twitter offers the illusion of data aggregation that tells you what large numbers of people think in the absence of a poll. The 24/7 news cycle demands hot takes, so despite knowing it's bad data, it's used, because the incentives demand publishing something. This reminds me of a lot of early globalization reporting where reporters interviewed a handful of urban elites living in, say, Cairo or New Delhi, and concluded everyone was becoming little Americans because they drank Coke, wore jeans, and talked like Americans. Fly into a capital, talk to a few people, and fly out.

3. Evolutionary cognitive biases: Humans evolved in small bands or tribes, and later lived in small villages for most of history. If ten people in a row said they hated you, it was probably a universal feeling. You were at risk of getting kicked out of the tribe/village, and you were going to die unless you stopped doing whatever they disliked. If you asked a question and 10 people (out of 20-30) told you the same answer, it was probably what pretty much everybody believed. Our minds are wired in this way, that is, to respond to a barrage of uniform opinions, especially from people who are prominent or known to us. It is incredibly difficult to counter these biases even when you know they exist, and most people, I estimate, don't even really understand they exist.