LAST WEEK, DONALD TRUMP explained that he was just kidding, or “being a bit sarcastic,” when he repeatedly promised to resolve the Russia-Ukraine war in twenty-four hours if elected, perhaps even before taking office. Meanwhile, his supposed peacemaking quest continues to limp along, generating plenty of news and plenty of confusion but no accomplishments—except for more evidence that, whatever the reason for it, his favoritism toward Vladimir Putin is real (though not total).

The good news: Ukraine is once again receiving the shipments of military aid from the United States approved under Joe Biden and allocated by Congress, and intelligence-sharing is back on. The resumption of aid came in response to the announcement by Ukrainian president Volodymyr Zelensky that Ukraine would accept the Trump administration’s proposal for a thirty-day ceasefire as a pathway to a durable peace agreement. Since there is no evidence that Zelensky was opposed to a ceasefire prior to the aid being cut off—even during the disastrous Oval Office sitdown of February 28, his only offense was to mention the need for guarantees that Russia would respect the truce given its history of violating such agreements in the past—it’s unclear what the interruption was for, except to assuage Trump’s ego after the “disrespect” Zelensky supposedly showed on his White House visit. Nor do we know how many Ukrainian lives, which Trump and JD Vance claim to be so concerned about, the pause may have cost: while it was too brief to noticeably affect Ukraine’s stock of weapons and materiel, even a brief suspension of intelligence sharing may have seriously harmed its ability to shield its citizens from Russian strikes.

Secretary of State Marco Rubio commented that, with the joint U.S.-Ukrainian ceasefire proposal—which does not mention security guarantees but does call for a full exchange of prisoners of war, the release of all civilian detainees held by Russia in occupied territories, and the return of Ukrainian children kidnapped by Russia since the February 2022 invasion—“the ball is now in [the Russians’] court.”

Putin’s response two days later, at a press conference with fellow dictator and key ally Alexander Lukashenko of Belarus, was a yes, but—or, as he put it, “We are in favor, but there are nuances.”1

And what are Putin’s “nuances”? Ironically, they look very much like a demand for “guarantees”—the very thing that Trump, Vance, and their supporters have lambasted Zelensky for discussing:

How will those thirty days be used? For Ukraine to mobilize? Rearm? Train people? Or none of that? Then a question: How will that be controlled?

Who will give the order to end the fighting? At what cost? Who decides who has broken any possible ceasefire, over 2,000 kilometers? All those questions need meticulous work from both sides. Who polices it?

In Putin’s case, the demand for guarantees is also hypocritical, given that Russia is the party that (1) started this war and (2) repeatedly broke past ceasefire agreements. What’s more, Putin is not offering to pause mobilization, military training, or rearming on Russia’s side and asking Ukraine to match that initiative; he’s implicitly asking for Ukraine’s hands to be unilaterally tied during the ceasefire.

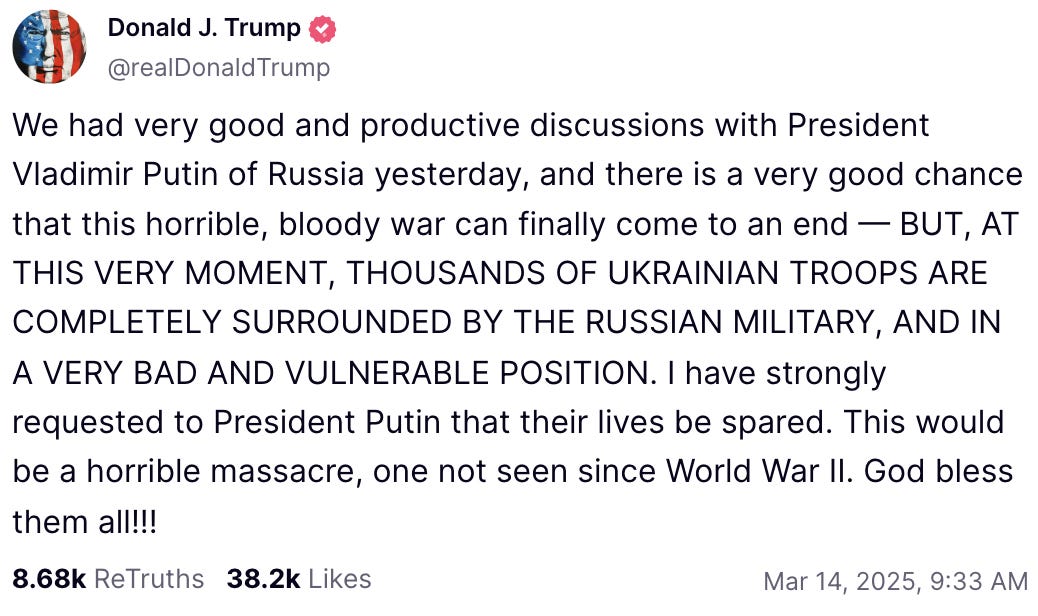

So, we could reasonably expect Trump to come out with an angry tirade blasting Putin for refusing to play ball when the ball was in his court, right? Well, not quite: Trump commented that Putin “put out a very promising statement but it wasn’t complete.” Trump also amplified Putin’s claim, made at the press conference with Lukashenko, that the Ukrainian contingent which had invaded Russia’s Kursk region last August is now almost completely trapped and about to be fully encircled.

At a meeting of Russia’s Security Council the next day—the topic of which was “the restoration of Russian-American relations”—Putin expressed “understanding” for Trump’s request and promised that if the surrounded Ukrainian soldiers laid down their arms, they would be “guaranteed their lives and dignified treatment in accordance with the norms of international law and the laws of the Russian Federation.”

Why it should take a request from the American president for Russia to promise compliance with international law and even Russia’s own law governing the treatment of prisoners of war is unclear—though Putin did claim, with no evidence, that Ukrainian troops in the Kursk region had “committed numerous crimes against civilians” and that those crimes would be qualified as terrorism by Russian authorities. (So far, the only reliable reports of crimes by military personnel in the Kursk region have involved looting by Russian soldiers, a problem acknowledged even by the region’s former governor.)

Even more saliently, however, there is also no evidence of “thousands,” or even dozens, of Ukrainian troops surrounded in the Kursk region. It’s not just a matter of firm denials from the Ukrainian side, including Zelensky; virtually all independent analysts, from the Institute for the Study of War to expatriate Russian journalist Ruslan Leviev, founder of the open-source intelligence group Conflict Intelligence Team—who sympathizes with Ukraine but has a long record of fair and accurate analysis—agree that no encirclement exists and that Ukrainian troops have been leaving the Kursk region in fairly orderly fashion after orders from Kyiv to withdraw. (They still hold some villages near the border.) What’s more, even most Russian military bloggers have been disputing claims that Ukrainian soldiers in the area are surrounded en masse. One even referred to Trump’s and Putin’s comments on the subject as a “performance” motivated by “ordinary politics and negotiations”:

Trump is trying to coax the Russians toward a ceasefire and coddling them in every way he can because he’s afraid to spook them, and Putin is using this to extract big concessions from Ukraine, since the situation on the battlefield favors the Russian armed forces and there is no great interest in a temporary ceasefire here and now.

In another sign of such “coddling,” Trump last week reduced his Ukraine and Russia envoy, retired Gen. Keith Kellogg, to envoy for just Ukraine—apparently because of complaints from Russia about Kellogg’s excessive pro-Ukrainian sympathies. And when Sky News reported that Trump’s loyal “fixer,” Steve Witkoff, was made to wait eight hours before Putin finally met with him, Trump reacted with a post angrily denying the slight and blasting “fake news” and “sick degenerates” in the media. “Until he wrote that, I wasn’t sure,” quipped Ukrainian TV journalist Olena Kurbanova on her YouTube show. “Now I have no doubt that Witkoff had to wait eight hours.”

There is one apparent stick among all the carrots: Trump has just slapped new sanctions on energy transactions involving sanctioned Russian banks, removing a Biden-era waiver and making it harder for Russia to sell oil on international markets. But émigré economist Vladimir Milov, who held several government posts in Russia related to the energy sector from 1997 to 2002, noted in an interview that the move had little effect on the Russian oil market, suggesting that Russia had already found ways to circumvent the restrictions. What makes sanctions effective, Milov explained, is not one big and scary cudgel but consistency in finding and closing loopholes—whereas “Trump’s rhetoric is exactly the opposite: it always revolves around the idea of some single lever that does not exist, while the loopholes are getting looser if only because there’s less oversight under Trump.”

And the U.S. sanctions may be left with even fewer teeth if Trump decides that Russia has shown sufficient goodwill to deserve a reward. Maybe that’s what those phantom encircled Ukrainians are for.

“PUTIN HAS NO INTENTION OF STOPPING the war. That’s it. There’s nothing to explain. It’s a position that they are openly, publicly declaring,” exiled Russian human rights lawyer and politician Mark Feigin told Kurbanova while Putin and Trump were performing their ritual peace dance. This is the consensus among independent Russian commentators as well as their Ukrainian counterparts—that Putin has no desire for either a ceasefire or lasting peace, unless the latter amounts to Ukraine’s full capitulation: massive territorial concessions, the dismantling of the Ukrainian military, no peacekeepers from NATO countries, and the installation of a puppet government in Kyiv.

Partly, Putin’s intransigence does appear to stem from his belief that he’s winning everywhere, reinforced by the Russian army’s rapid success this month in dislodging the Ukrainian army from its stronghold in the Kursk region. He may also believe that ending the war without a resounding victory—one that he can sell not only to the general public but to the hawks and the war veterans—may create far more problems than it will solve. For example, an end to the war will mean flooding Russia with hundreds of thousands of embittered ex-soldiers, many of them also ex-convicts.

In reality, the situation on the front is not that great for Russia. The retaking of the Kursk territories takes away a potential bargaining chip from Ukraine and ends a national humiliation for Russia. But there may be a certain symbolism in the fact that when Putin made a TV appearance in what was said to be a Russian command center in the Kursk region wearing military fatigues, he cut a rather pathetic figure. (Critics scoffed that he looked like a retiree moonlighting as a store security guard or a miserable elderly draftee.) Meanwhile, Russia’s advance in Ukraine is basically stalled; cities whose capture was being predicted last fall, such as Pokrovsk and Toretsk, appear to be safe for the moment, and Ukrainian troops have even been able to recapture some villages and push the enemy back. While the future of U.S. assistance is up in the air under the current administration, Europe’s determination to step up to the plate seems genuine—and Ukraine is also making headway in helping itself: Right on the heels of two barrages of drone attacks that rattled Moscow, it has apparently hit a Russian oil refinery with a domestically produced modified “Neptune” missile capable of a 1,000-kilometer range. And the economic resources supporting Russia’s war machine may finally be running out.

It’s hard to say to what extent Putin, living in his bubble of lies, is aware of these looming problems. But it seems fairly clear that he hopes Trump will bail him out by forcing Zelensky into a bad peace that will become a frozen conflict and set the stage for a new low-key hybrid war intended to bring Ukraine to heel. And it is entirely plausible that Trump will try to oblige—for instance, shifting the blame for Putin’s intransigence to Zelensky when the Ukrainian president refuses to submit to Putin’s unacceptable conditions, or crediting Putin’s claims of supposed Ukrainian war crimes in the Kursk region.

Notably, the American public remains strongly pro-Ukraine despite the Trump-induced dip in support among Republicans. In a new Quinnipiac poll of registered voters, 62 percent say supporting Ukraine is in the national interest of the United States while only 29 percent say it is not. More than 60 percent think Trump’s attitude toward Russia is not tough enough, and 56 percent disapprove of the pause in aid to Ukraine.

All of which is to say: This is a crucial time for Americans who support Ukraine’s cause to let their opinion be known and signal to Republicans that there will be a political price to pay for betraying Ukraine.

“But there’s a nuance” is the punchline to a well-known, very crude Russian joke in which the “nuance” amounts to which one of two men is literally screwing the other. Was Putin winking to Russians who see him as their tough-talking macho leader? Given the Kremlin autocrat’s penchant for illustrating his points with this kind of humor, it certainly can’t be ruled out.