QAnon and the Satanic Panics of Yesteryear

What they can teach us about what to expect.

Many details concerning the beliefs of QAnon are bizarre and difficult to piece together. Ambitious works of journalism, decent explainer articles, and even a vast and messy Wikipedia page can’t quite do justice to its tangled, knotted, shifting conspiracy theories. But in its most simplistic form, QAnon holds that a secret group of Satan-worshipping, cannibalistic pedophiles has been running a global child sex-trafficking ring. This supposed cabal is linked to the power brokers of the Democratic Party; Hillary and Bill Clinton are typically said to play some kind of prominent role. There is more—much, much more—but that charge is at the core of QAnon.

Of course, the belief that the country is in a state of moral decline, full of corrupt elites and ungodly politicians, is nothing new in American politics. But it is worth remembering that even the more wild and unhinged accusations of Satan-worshipping have a long history in this country—and by studying the precedents, we might be able to better understand the dynamics and future of QAnon.

When, at an NBC town hall event last October, former President Trump was asked if he would disavow QAnon, he professed ignorance and a touch of apparent admiration:

I know nothing about it. I do know they are very much against pedophilia. They fight it very hard. . . . I just don’t know about QAnon. . . . What I do hear about it, is they are very strongly against pedophilia. And I agree with that. I mean, I do agree with that.

Even though Trump occasionally retweeted QAnon messages, and even though he was a central figure in the QAnon mythos (and was even believed by some true believers to be “Q” himself), it seems plausible that he really was unaware of much about it beyond its opposition to pedophilia. Someone with superficial knowledge of QAnon, mostly encountering its anti-child-abuse social media hashtag (#SaveOurChildren), might come away thinking that its activism against pedophilia was reasonable and commendable. It is not surprising, then, that some curious Christians, concerned about child welfare, might initially find themselves drawn to it for that reason.

QAnon is on the political fringes but its beliefs about mysterious Satan worshipers fall into a well-established pattern of Christian theology concerning conspiracies dating back to the medieval church and the witch hunts of the early modern era. The fear that children are being morally corrupted, sexually abused, and physically harmed is one of the most recognizable Satanic conspiracy tropes. In the witch trials of early modern Europe, accusations of killing infants and harming young children were common. For centuries, Jews throughout the Holy Roman Empire and Reformation Europe were accused of ritually murdering Christian children for magical purposes and cannibalism. Under stress and torture, both men and women—but mostly women—confessed to such Satanic crimes as using babies’ blood for spells, murdering children at witches’ sabbaths, and having sex with the devil.

(Ironically, similar tropes had been deployed against the early church by its Greco-Roman critics: Ancient Christians were accused of cannibalism and sexual perversion.)

America’s most infamous witch hunt had its origin in the fear of Satanic harm befalling children. Beginning in 1692, Salem minister Samuel Parris and his wife Elizabeth were alarmed at their daughter Betty and niece Abigail’s declining health. The Reverend John Hale suspected a Satanic attack: “These Children were bitten and pinched by invisible agents.” Believing them bewitched, fears of a Satanic conspiracy against the colony took hold—ultimately costing twenty lives.

Often, Satanic panics occur in the context of apocalyptic environments. Storms, famine, and war were common precursors for witch hunts in the medieval world. The Salem witch trials were preceded by the devastation of King Philip’s War and the political unrest of the Glorious Revolution. Before the Satanic panic of the 1980s in the United States, there had been more than a decade of political upheaval, economic recession, and energy disruption, not to mention the sexual revolution and a quickly changing youth culture.

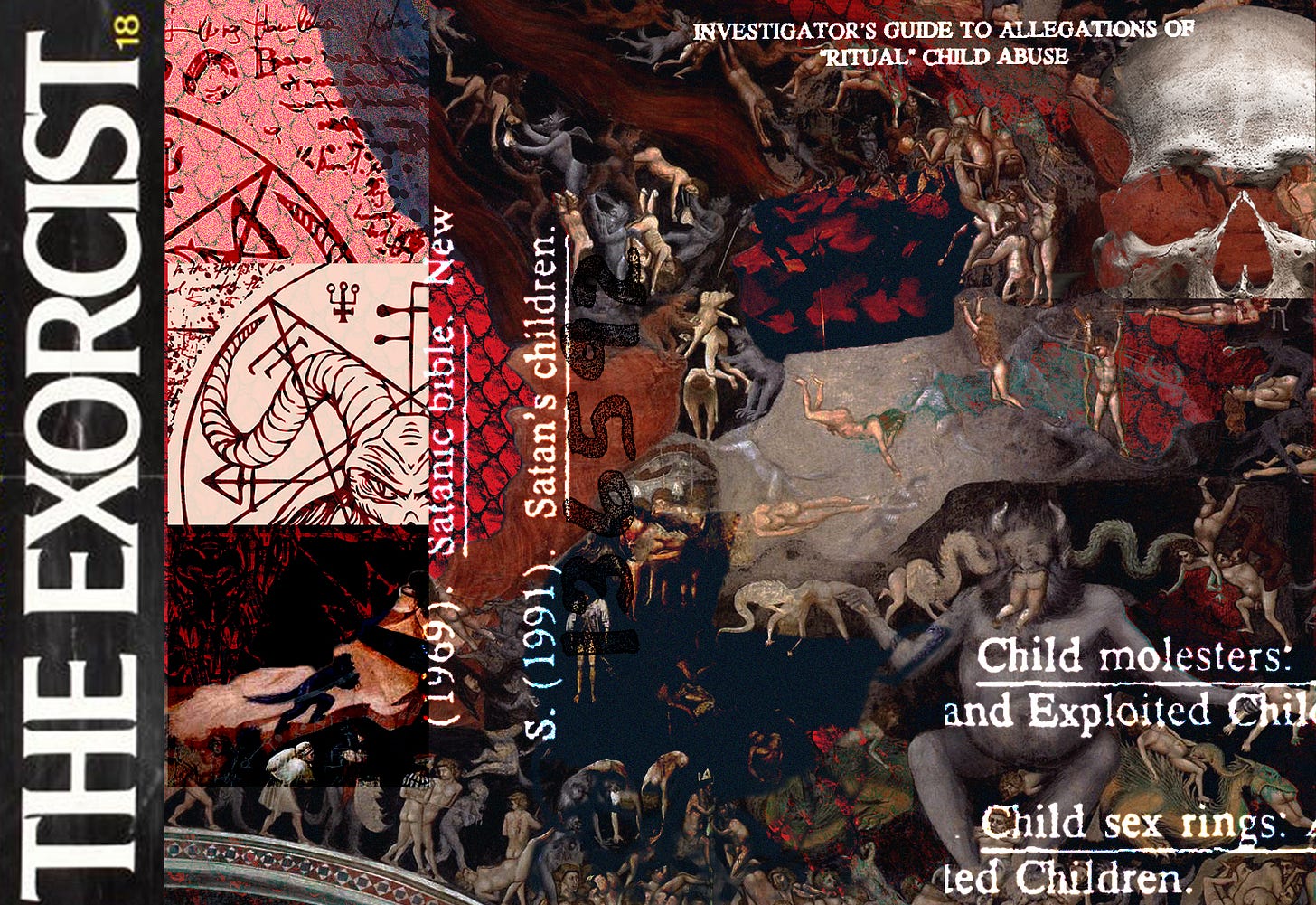

More proximate factors connected to the 1980s panic included the rise of heavy metal bands, some of which adopted morbid imagery; the success of Dungeons & Dragons; and the growing pop-culture fascination with the demonic and the occult, as in the films Rosemary’s Baby, The Devil Rides Out, The Wicker Man, and The Exorcist. Further contributing to the cultural milieu were the gruesome and bizarre violent crimes that had captured national attention in the preceding years—the Manson murders, the Zodiac Killer, the Night Stalker. There was worry about copycat killings. The AIDS scare, the growing awareness of such spiritual alternatives as New Age and Wicca, and concerns about child safety (“stranger danger”) added to the sense of dread.

It was in this context that memoirs began to be published concerning supposed Satanic cults and survivors of demonic possession, the most famous being Michelle Remembers (1980). Crimes with supposed connections to Satanic activity began to emerge, with the only evidence derived from the (subsequently discredited) practice of “recovered memory.” There arose a shocking, and frankly implausible, volume of accusations of child abuse by devil-worshipping cults at day cares, like those in Kern County, California. Soon an industry of so-called Satanic cult experts emerged, ready to offer their “expertise” to law enforcement and in courtrooms, as well as offering seminars and classes for the masses. For example, Dale W. Griffis offered his testimony as an expert on Satanic cults in the notorious trial of the West Memphis Three, despite having received his degree from an unaccredited university (a point the defense made).

An exhaustive Department of Justice report concluded in 1992 that “there is little or no evidence” for allegations of “large-scale baby breeding, human sacrifice, and organized satanic conspiracies.” Given the lack of evidence and the backlash from friends and families of some of the people being accused eventually, the Satanic panic eventually began to subside. But it left behind enormous damage—including families splintered by false accusations and innocent lives wasted in prison after false accusations of Satanic ritual pedophilia.

The past several years have again been a time of unsettledness—of war, recession, the tumultuous Trump presidency, constant talk of planetary ecological ruination, and now a global pandemic—so no one should be surprised that fears of Satanic activity have once again sprouted up. To put it another way, it might not take much nowadays to convince a person that we are living in the end times.

One of the reasons why doomsday thinking is important to the promulgation of Satanic panics is how it complements a feeling of intensified persecution. On issues ranging from abortion to marriage to drugs to how history is taught, many conservative Christians feel like cultural walls are closing in on them—a feeling of persecution encouraged by talk radio, cable news, and online personalities. Liberals may disregard these concerns as overblown and progressives may consider them illegitimate, but many conservative political and religious figures find themselves hopeless or even panicked.

But if the rest of the world is sliding into damnation, QAnon’s supposed fight against Satan’s followers can be seen as pure, faithful, and defiant. QAnoners see themselves as heroes, the faithful remnant as spoken of in Revelation.

As historian John Fea has argued, the fear that America’s Christian identity is eroding can partly explain the appeal of Trump as a “fighter” trying to win back the country for conservative Christians. This perception of a Christian nation in religious freefall fits almost seamlessly with QAnon’s conviction that the United States is under spiritual assault.

So, if QAnon is less an anomaly than it is the next chapter in America’s horrified fascination with the devil, fitting within the Christian framework of apocalypticism, persecution, and demonology, what might we expect to come of it in the months and years ahead?

First, future incidents of violence should not surprise us. The “Pizzagate” conspiracy theory that was a precursor to QAnon nearly led to bloodshed, and among the January 6 rioters at the Capitol were QAnon true believers. When the stakes are believed to be so high—with children’s welfare and lives, not to mention the spiritual and temporal fate of the world, supposedly on the line—a resort to violence may seem not desperate but reasonable.

Second, the most novel aspect of this Satanic panic—the wide reach and rapid evolution of the conspiracy theories, made possible by social media’s ability to rapidly spread misinformation—will continue to be a factor. There are all sorts of ways that these conspiracy theories can start to reach new mainstream audiences, as certain Facebook, Instagram, and Twitter accounts create bridges between the most rabid participants and the uninitiated. One area to stay focused on is parental influencers, especially given the power of simplistic ideas that can be distilled in catchy hashtags like #SaveOurChildren.

Third, we have reason to hope that QAnon will eventually spend itself out. If the Satanic panics of the past can teach us anything, it is that many of these individuals—including many whose beliefs are bizarre or seem like they must be ironic—are sincere in their convictions and mean well. They want wrongs to be righted and they want justice to be done. But eventually, they will move on. We don’t know when that will be; it’s entirely possible that the climax of QAnon already came on January 6, or perhaps the movement will linger on for years in ever-shifting forms. But Satanic panics tend eventually to peter out, and to be looked back upon with some mix of shame and horror.

The trouble is they tend to be forgotten, until Satan supposedly strikes again.