Reconstructing Erna

For one brilliant artist and her Jewish family in 1930s Vienna, self-remaking was a necessity of survival. But there were some harms from which their self-reconstructions could not protect them.

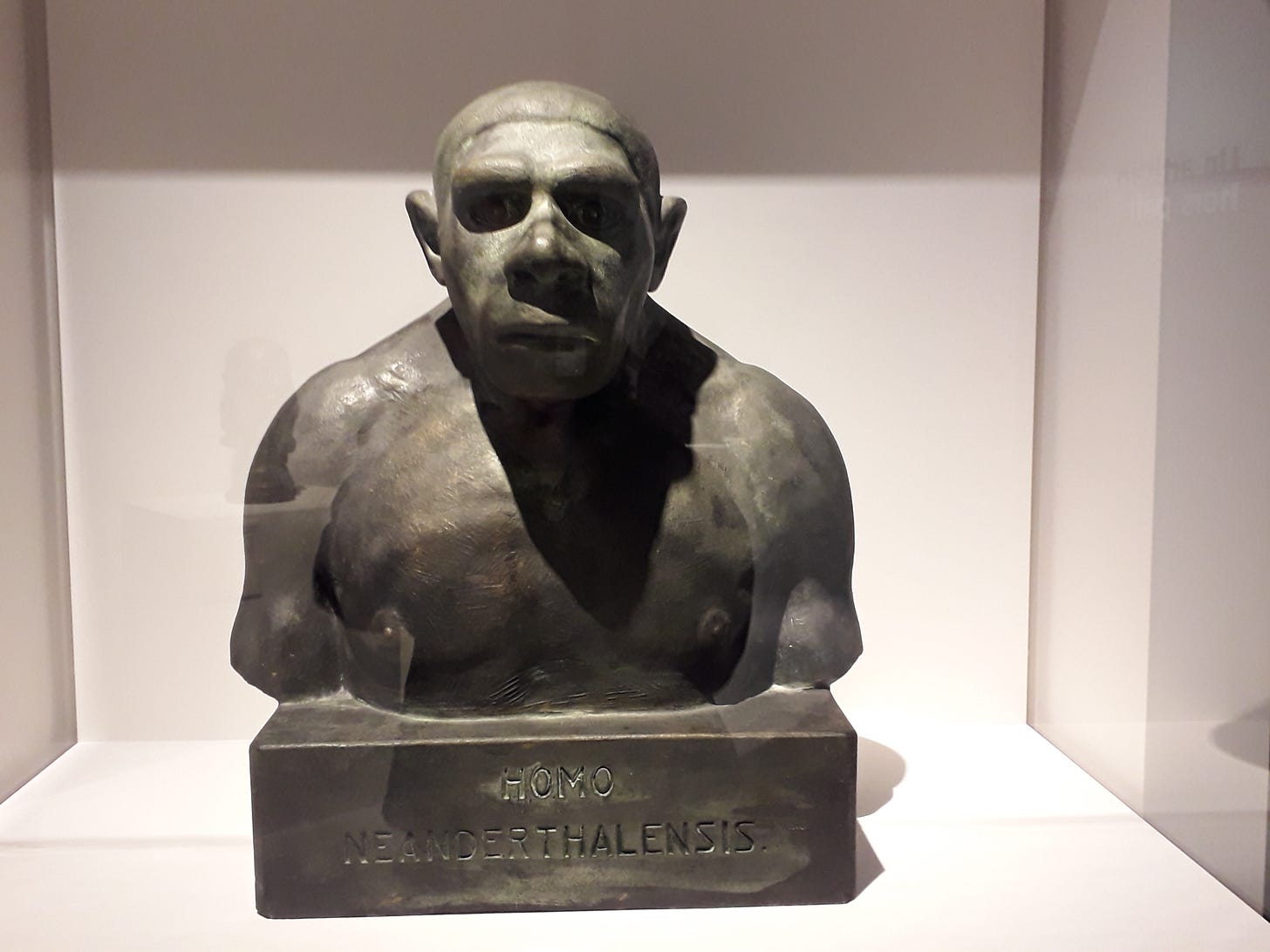

THERE WAS A TIME WHEN Erna Baiersdorf Engel-Jánosi was known for her way with men. A talented and creative sculptor who lived from 1889 to 1970, she found a special niche in creating busts to represent our species’ genealogical forebears. Partnering with a German scientist, she was among the first to reconstruct the Neanderthal man; the plaster busts they created together in the 1920s were distributed and studied in museums, galleries, and schools throughout Europe before the Second World War. Her work shaped many of our ideas of what early humans looked like.

I discovered Erna while researching my mother’s Hungarian family. Erna’s husband was named Róbert; he and his brother, Richárd, fought for the Austro-Hungarian Empire during the First World War. Neither one would survive beyond the next conflict. Richárd returned home to Pécs, Hungary after the war only to die years later in Mauthausen, a concentration camp in Austria. Róbert also returned to Pécs, divorced his first wife, and married Erna. His life would be claimed by disease.

Róbert had a daughter, Rose, who became Erna’s stepdaughter; Rose’s children, Anna and Gábor, became Erna’s step-grandchildren. And Anna had a cousin: my mother. But my mother never knew any of her Hungarian cousins, aunts, or uncles. That’s because my mother’s French Catholic mother, Carlette, and my mother’s father, Friedrich, a history professor, never told her about his family in Hungary.

While on a Fulbright, I lived and worked in Pécs for five months researching the Engel-Jánosis. I got to know Róbert and Erna, who were unknown to me before. Studying archival materials from Yad Vashem and other museums and going over my mother’s wartime passport, documents, and old family photographs, I learned a lot about the people they were and the passions that drove them. I also came to understand something of the quiet, years-long suffering my mother and other family members endured as a result of the agonizing antisemitic propaganda that accompanied Hitler’s rise to and consolidation of power.

The Engel-Jánosis were a brilliant, influential family. Most of them were murdered in the Holocaust. But a few survived. Those who did managed to do so by reconstructing themselves—remaking their identities to minimize their exposure to a system that wanted to destroy them. But sometimes those reconstructions exposed them to other, insidious harms.

The Engel-Jánosi men thought they would be protected from Nazi annoyances by the armor they had fitted around their lives in Pécs. They arrayed themselves in their loyalty and allegiance to the Austro-Hungarian Empire, their important family name, their estates, their money, businesses, and property, their important contacts and friends. Róbert and Richárd thought these things would shield them from Hitler and the political movement he represented, which was typified by the antisemitic laws he announced at a rally in Nuremburg in 1935—the same year my grandfather Friedrich became an associate professor in modern history at the University of Vienna.

The Nuremberg Race Laws codified Hitler’s twisted ideas about racial purity (and contagion) and invested them with the authority of the state, that jealous protector of a monopoly on violence. And the Nazis accepted this because, for them, Hitler came first—above God, above family, above friends and neighbors, and above country. To the Nazi mind, Jews were a separate race, inferior, troublesome. The road to extermination was becoming clear.

It was in response to these laws and the Nazi hatred they embodied that Erna, her step-granddaughter Anna, my grandfather Friedrich, and my mother began to reconstruct themselves. They survived the Holocaust. But they also carried part of it forward with them.

Some members of my mother’s family changed their surname, wiping out the Engel to distance themselves from their Jewish roots. In 1919, it became illegal to write the prefix von or de, those prefixes signifying nobility, in a surname, so Engel de Jánosi or Engel von Jánosi became Engel-Jánosi. But even in hyphenated form, the name would risk making an agent of the state pause because of that “Engel.” So some family members simply became Jánosi.

The name changes, common among Jewish people during that period in Hungary, presented one significant obstacle to my search. My relatives’ silence about their pasts presented another, and both of these were set in front of a major barrier: the whitewashing of history in Austria and Hungary. With the number of Holocaust survivors shrinking every year, my ongoing search for lost relatives has proven challenging. It’s taken me years to recreate my mother’s family tree, and even then, I still don’t have a full picture. But a lost and found family is still a family.

Reconstructing a life takes time. I dig through layers of stories I’ve heard or read, those earlier reconstructions, to find what might lie underneath. And sometimes I dig where I have no stories to go by at all. My mother never lied about who she was—she just didn’t talk about her past.

I read old letters, comb through old passports and travel documents, and search online archives for more information. Why? Maybe because I’m trying to figure out a pattern, a key that unlocks the evolution of a life and a family. How do people survive the violence and insanity of a time such as theirs? What choices do they make while somehow maintaining their dignity, character, and sanity?

Mostly, I focus on the facts, even when the facts are troublesome—even when they don’t fit my assumptions.

The Scientific Sculptor of Early Humans

IN A 1938 PRESS PICTURE taken at her home in Pécs, Erna leans against a fireplace mantel, sure of herself in a wood-paneled room, surrounded by her plaster busts of Neanderthal Man, Homo aurignaciensis, and Homo ultimus, the Conquering Hungarian. She and the busts of the men she recreated are at the height of their fame. I now understand the woman in that photo was putting on a brave face amid worsening hardship and danger.

Known for her pioneering work in anthropological facial reconstruction, Erna was an artist, but in the picture, she wears the white lab coat of a scientist. She also brought the interests and questions of anthropology to her work. Through her facial reconstructions of early hominids, especially, Erna wanted to educate humans about humans through art.

Born Erna Baiersdorf de Erdősi on September 24, 1889 in Vienna, she grew up painting and sculpting. Later, she studied art in Vienna and Budapest. She also developed an interest in new scientific understandings of our species and its origins.

She paid attention to bones, the shape of a skull, and how prehistoric man hunted, made tools, and art. Keen on evolution, Erna also paid attention to how humans needed to recreate themselves to survive.

In 1908, the brothers A. and J. Bouyssonie discovered an almost complete skeleton of a male Neanderthal buried in the limestone bedrock of a small cave near La Chapelle-aux-Saints, France. French paleontologist Marcellin Boule created and published the first reconstruction of the Neanderthal man in 1911. He depicted his subject as bent over, more ape than human, and less advanced than Homo sapiens. Boule claimed his scientific reconstruction corroborated the then-popular theory that humans could not be related to Neanderthals. Later scientists would determine that Boule had misinterpreted the fossils, imposing assumptions that prevented him from understanding them correctly. (He even gave his Neanderthal opposable big toes, a simian feature with no apparent basis in the specific fossil he was using as a foundation.) The skull, they found, must have belonged to a very old fellow; it showed signs of “gross deforming osteoarthritis” so advanced that it’s possible another person would have needed to chew his food for him to be able to eat. Boule’s depiction was a false, tendentious reconstruction.

In the next decade, Erna became known for a different approach: the “soft tissue thickness method.” This entailed building up layers of clay representing anatomical features like muscle and fat; the thickness of each layer was determined by, among other things, an analysis of the attachment marks left on a fossilized Neanderthal skull. She helped pioneer a reconstruction workshop during this time at the Kunsthistorisches Museum in Vienna, and she eventually worked with a German scientist there to create two soft-tissue reconstructions of the Neanderthal man discovered in La Chapelle-aux-Saints. Her time-consuming technique was labor intensive, but it helped give depth and realism to the Neanderthal’s appearance. The results also made him look more human.

These reconstructions were widely distributed throughout Europe. Other scientists and artists visited the museum to study Erna’s methods. Her work changed how her colleagues across the continent reconstructed mammals. She also helped to reshape how people saw early humans.

A Rising Tide of Antisemitism

MY GRANDFATHER, FRIEDRICH, KNEW ERNA as the wife of his cousin Róbert. A historian and a devout monarchist with conservative beliefs, Friedrich lived in Vienna and traveled by train at least once a year to Pécs to attend gatherings at the family estate near a coal-mining village called Komló. The family operated the mine and a successful lumber business with factories in Hungary and Austria. Wood was harvested and loaded on trains in Pécs, then delivered to a factory in Vienna, where it was processed into slats for parquet floors. My mother remembered jumping up and down on the boards as workers unloaded them at the factory in Vienna; her cousin Anna remembered jumping up and down on the boards as workers loaded the trains in Pécs.

My mother didn’t know Anna or Erna back then because her father Friedrich didn’t take her to Hungary with him on trips to see their extended family. Friedrich was raised Jewish, but over time, he distanced himself from his relatives. He married a Catholic woman from Paris. They baptized their only daughter—my mother, born in 1929—and raised her Catholic.

In 1937, responding to bans on the distribution of books written by Jews, Friedrich’s publisher—recall that he was a historian—wrote a letter to the Reichsschrifttumskammer (Reich literary chamber) saying that Friedrich had been a member of “the Austrian Heimwehr,” so there was no reason for Nazis to prohibit the distribution of his latest book. In essence, Friedrich’s publisher told them: Look, he’s one of us. I don’t know if Friedrich really did belong to this far-right-wing paramilitary group. If he did, it didn’t help him: The Reich banned the book’s distribution anyway.

Still, my grandfather continued teaching at the university while his mother and his wife saw to the details of the family’s parquet-floor business. Friedrich didn’t like working in the factory. He preferred researching at the Austrian State Archives, arguing methodology with academics, going for walks with Otto von Habsburg, and traveling to Rome to study the doctrines and history of his chosen faith. Friedrich’s academic specialty was modern European history, but he refused to believe what was happening in Austria and in Europe. He chose to live in a beautiful bubble within a larger, charmed world of his own making.

Reality sometimes forced its way in regardless. My mother was 9 years old at the dentist’s office in Vienna having a cavity filled when the dentist and the nurse stepped away to watch a parade. My mother joined them at the window, looked down, and saw Adolf Hitler, unmistakable with his droopy hair and fat black mustache. He was riding in an open car, and she clapped along with everyone else as he went by. This was March 1938, the time of the Anschluss, when Adolf Eichmann, the SS chief appointed to “liquidate European Jewry,” declared his intention to free Austria of Jews.

The Nazi Party proclaimed that only racially pure Germans could be German citizens, and the Reich Citizenship Law codified this idea when it defined a citizen as a person who is “of German or related blood.” Because Jews were defined as a separate race and could not be German citizens, they had no political rights. And any person with at least three Jewish grandparents was consigned to this racial category.

Friedrich’s parents were practicing Jews. His father died in 1924. The Nuremberg Laws put both Friedrich and his wife and daughter—my mother—in danger.

One afternoon, my mother saw Nazis outside her home, beating her neighbor and friend, a Jewish merchant. Another afternoon, a blond-haired boy in a Hitler Youth uniform wouldn’t allow her on an ice-skating rink.

My grandmother told my mother not to go to the ice-skating rink anymore. She also told her to trust no one.

AFTER THE ANSCHLUSS, Erna was fired from her job at the Kunsthistorisches Museum because she was a Jew. She was not allowed to sell or display her statues at other museums or galleries, either. Erna’s colleagues removed her work and any references to her work from their books and articles. She couldn’t find work in Austria or in Hungary.

In 1939, the Royal College of Surgeons invited Erna to spend the summer in London to create statues of the different phases of child development. That July, she also gave a lecture for the British Federation of University Women at Crosby Hall. She discussed recreating the likenesses of early hominids from the skulls of fossils, among them the “frightful” Rhodesian Man from Broken Hill, and, her favorite, the Aurignac man. Like other successful prehistoric species, the Aurignac man had “keen powers of observation” and constantly adapted to change. She said it was clear that this combination was how he survived and found joy. He could make art out of anything. “From elephant tusk and reindeer antlers,” this ancient ancestor of ours “created beautiful small sculptures” like the Venus of Willendorf, the faceless 29,500-year-old statuette that was dug up in 1908.

That summer, Erna’s sister Margit and Margit’s husband, Otto Reif, fled Nazi-occupied Austria for London. As Jews, they knew they were in danger. For days, Margit tried to talk her sister into emigrating to Vancouver, Canada with them. Erna refused.

Survival Through Reconstruction

IT WAS AROUND THIS TIME, as the Nazi threat became fully realized, that Erna’s family began to reconstruct themselves in earnest. They knew what they had to do to survive.

My grandfather Friedrich, the convert to Roman Catholicism, and his small family lived with his mother, Marie, in Vienna. She did not follow him into the Catholic Church, and the division created some enmity between them. For a time, Marie stopped talking to her son.

The race laws forbid Jews from teaching, and Friedrich was not protected from them. On April 22, 1938, the ministry of education rescinded his venia docendi (teaching license). The University of Vienna summarily fired him.

In school, my mother’s teacher asked the class every morning if any visitors had been to their homes the previous evening. She had them write lists of all their parents’ friends. This teacher was a relative of Hermann Göring, and she also kept lists of her students’ height and the color of their eyes and skin.

After the Nazis occupied Austria, Austrian passports became invalid. Citizens who wanted to travel were required to apply for Reissepasses, German passports, which required an interview.

My grandmother Carlette’s marriage to Friedrich had become illegal. Her brother and mother were living in Switzerland and France at the time, and they wrote to Carlette, urging her and the rest of the family to leave Austria.

That October, my grandmother spent days standing in long lines at the consulate’s office for her new Reissepasse. My mother said that every day before she left the house, Carlette carefully dressed, reconstructing herself for the task. She would wear her best coat and hat—the one with the netting—plus gloves, expensive shoes, and a purse stuffed with cash for bribes.

Bribes notwithstanding, however, Nazi law required my mother and Friedrich to appear on their own behalf before the police department for temporary Reissepasses, which they had to carry at all times and get stamped once a month at the police department.

Who knows how they managed it, but both must have felt lucky that neither of their passes was marked with a J for Jude.

Beginning October 29, 1939, my mother always carried a Kinderausweis, a child ID card, valid until she was 15. I found it among her things after she died, amazed that she kept it all those years. The paper is worn thin. It said that she was 10 years old, and that she was number 957. Already they were training her to think of herself as a number.

The SS muscled their way into my mother’s home in Vienna one night to search the place—for what, nobody knew. Friedrich made sure to leave papers bearing the Vatican’s letterhead on his desk. The SS made a list of everything in the house, including all the furniture, rugs, artwork. They opened drawers, pulled books from the library, scattered paper. They left that night without making any arrests, but the threat to my mother’s family had become real in a new way.

For the next year, my grandparents spent all their money on bribes and tickets. With the help of family, the Society of Friends (Quakers), and a sympathetic dean who gave Friedrich an offer to teach at King’s College, Cambridge, they split up and slipped away. Each carried only one small bag, so no one would notice.

They left at night. Friedrich went first—because, he said, he was the one most in danger. He left behind his mother, his wife, and his daughter.

My mother left with her mother by taxi on a cold spring night in late April 1939. My mother wore a dark blue coat several sizes too big. She had the red measles, which had spread into her eyes. She told me that even though she did not cry, there were still tears. Carlette wore good Italian shoes, a fox fur scarf, and a hat with a black net covering her face. She told my mother not to look back—to never look back. My mother did as she was told.

When the train reached the first border crossing, the guards demanded to see their papers.

“Sehr ansteckend!” Very contagious! My grandmother said it through the cabin doors, insisting on keeping them shut. She knew the Germans’ fear of germs. The guards hesitated but kept their distance. They asked that the women slide the papers under the door, which my grandmother did. The men kept their gloves on, holding the documents at the corners and quickly stamping them without checking for suspicious words like Engel.

After Friedrich reunited with his wife and daughter in Switzerland, the three took a train to Lyons, France, where they stayed with relatives. In late summer, they traveled to England and split up again. My grandparents sent my mother to stay with a family in Whitchurch to keep her safe from German bombing. On the train, my mother sat alone, reading the dictionary to learn English.

This put my mother and her parents in England at the same time Erna was there. But they never connected.

On March 12, 1940, my mother and her parents boarded a ship called the Scythia, docked in Liverpool. By that time, my mother knew English as well as French, German and Italian. Like Erna’s Aurignac man, she had learned to adapt.

The parents and daughter were each asked if they were polygamists (no) or anarchists (no).

According to the ship’s manifest, their reason for coming to the United States was “to teach at Johns Hopkins University,” which was listed as their sponsor. Another academic job offer that helped save their lives.

Under the heading “race or people,” the manifest lists my grandmother as “French.” My mother and grandfather received another label: “Hebrew.”

Hebrew.

For my mother and her father, that one word might as well have said: shame.

Hitler lost the war, but he won on so many other fronts. My family did not escape the range of all of the Nazis’ weapons. Their propaganda, the fear they created, and their poisoned ways of thinking could reach all the way around the world.

In the last month of her life, at 92, my mother imagined men in the telltale gray and black uniforms standing around her bed, coming for her.

I keep my mother’s Kinderausweis in my top desk drawer. Sometimes I examine the stamps and signatures with a magnifying glass. Whoever you were, Paul Dean Thompson, American Vice Consul in London, thank you and bless you. We owe you our lives.

The Holocaust Arrives in Hungary

ERNA DID NOT LEAVE ENGLAND with her sister Margit in 1939. While Margit went on to Canada, Erna went back to Hungary to be with her husband, Róbert.

By this point, the country was rapidly moving to the far right. In the late 1930s and early 1940s, Hungary passed similar anti-Jewish laws to those that had spread elsewhere in Europe. These prohibited marriage and sexual relations between Jews and non-Jews and banned Jews from owning or purchasing land. The Engel-Jánosis could no longer own their homes or businesses outright.

Erna and Róbert must have talked about leaving. By then, word was out about the camps, but like so many other Hungarians, they still didn’t believe their neighbors, friends, or country would betray them. Róbert and his brother Richárd were decorated veterans of the Great War. Surely, that counted for something. Besides, Hungary wasn’t even in the new war. Not yet.

They didn’t want to leave. Although she couldn’t find paid employment, Erna was free to work on her sculptures at home. She was teaching her 9-year-old stepgranddaughter, Anna, how to paint and sculpt, too. While Erna worked, she gave Anna plaster to shape her first statues.

Though they hadn’t left Europe, the couple and the larger family had adapted in other ways. Róbert and Erna converted to Catholicism along with Róbert’s daughter, Rose, and Rose’s family. But Richárd did not convert, even though his girlfriend, a Catholic, begged him to do it. He stopped talking to his brother in the wake of their religious divergence.

Then, amid the new anxiety and uncertainty of this period, Róbert contracted tuberculosis. He died on July 30, 1943, leaving Richárd running what was left of the family business.

Germany occupied Hungary last, and in 1944, Eichmann took on the task of murdering the country’s remaining Jews. According to Hannah Arendt, Eichmann found the Hungarian Gendarmerie and Hungarian Arrow Cross “more than eager to do all that was necessary” to help him achieve his aims. They arrested and loaded Hungarian Jews into cattle cars bound for the camps, and they took their victims’ houses, businesses, and jobs. Eichmann said that everything “went like a dream.”

In the spring of 1944, the Hungarian Gendarmerie ordered Hungarian Jewish citizens to report to the authorities.

Hungarian officers working with the Nazi SS arrested Richárd in front of his house in Pécs on March 19, 1944 around 1:00 p.m. The public display of hostile, searching power, and the targeting of a prominent and respected local businessman, served as a warning to the rest of the family and their larger community: None of them was safe.

After Erna’s stepdaughter, Rose, saw Richárd arrested, she quickly arranged to hide her children Anna and Gábor with Catholic nuns in the countryside. She and her husband would then try to escape to Budapest.

For the crime of being Jewish, Richárd was locked in an internment camp in Pécs for over a month.

In 2011, when I was in Pécs, the director of Tímár House (the Pécs historical museum) said the internment camp never existed. But Yad Vashem has evidence and eyewitness accounts of the camp. It was torn down right after the war.

The internment camp was the first stop in a larger grim itinerary. The Hungarian Gendarmerie loaded Richárd into a cattle car along with thousands of other Hungarian Jewish citizens from Pécs for a half-week journey to Austria. They received no food or water during their transport.

At the “Wailing Wall” inside the gates at Mauthausen, SS officers questioned Richárd, slapped him, and called him a dirty Jew. Then they remade him according to the precepts of their genocidal system. First, they gave him a label: “Ung. Jude.” “Ung” was short for Ungarischer (Hungarian), so: Hungarian Jew. Then they gave him a number: 64240. Finally, they changed his name. His surname is listed as Engel. Jánosi, behind which other members of the family had hidden their ethnic identities, was taken away from him.

Five days after he arrived, Richárd collapsed. Mauthausen records show that someone drew a black line through his name, not his number. The person was gone, but the body remained.

Richárd never attempted to reconstruct himself. He didn’t convert. He didn’t hide who or what he was. Left exposed, he was destroyed. They almost stole even the memory of him.

I discovered Richárd at the Yad Vashem archives in 2008 when I typed my mother’s maiden name into their database. “You’re the first to ask about him,” the archivist said. “No one has ever asked about this man, your relative, Richárd.”

“You are responsible now,” the archivist told me. “You must remember him.”

That’s what I’ve been doing ever since. And remembering Richárd, Erna, and every other lost family member requires reconstructing them—putting aside false narratives forced on them from without, and sometimes, resisting false narratives they internalized, deep within, while trying to survive.

The Only Way Out

IN PÉCS, A CATHOLIC FAMILY agreed to hide Erna. Then they turned her in.

The Hungarian Gendarmerie marched Erna and approximately 6,000 Jewish citizens of Pécs to the railroad station, where they were detained, then shoved into cattle cars headed for Auschwitz.

The air was thick with smoke that smelled like burning hair, according to accounts from other prisoners admitted the day Erna walked under the iron gates that bore the terrible inscription of a false promise: Arbeit Macht Frei.

Erna stood in line on the ramp where Josef Mengele surveyed newcomers. People he sent to the left went to the gas chambers. Nicknamed the “angel of death,” Mengele conducted experiments based on Nazi racial theory on Jews and Roma.

Maybe Erna knew something when she saw Mengele. When her time came, she said her birth date was 1906 instead of 1889, attempting to pass as a 38-year-old woman even though she was 55.

Mengele sent most Hungarians, many of them Erna’s family members, to the left that day, but he declared Erna “fit to work” and sent her to the right.

Erna was tattooed with the prisoner number 25086. She was Polit. Jüdin (political prisoner, Jew), and, according to the records, she worked as a “Pflegerin” (medical attendant).

Who knows how it happened or when. Maybe at some point in the camp, Erna channeled the Aurignacs, who had used whatever was available to create art. She found paper scraps and charcoal, and she began sketching SS officers, taking care to make them look handsome, muscular, and powerful. They gave her food for the drawings. They let her keep her red hair.

Her art saved her life.

Erna knew about vain men. She had lived and worked in a world of men, but she also knew about art and prehistoric survival.

Word got around about the artist from Pécs. Other officers ordered Erna to sketch them, too. She drew what she knew would please. She must have struggled drawing flattering portraits of men who wanted to murder her.

A month before the Russian Army liberated Auschwitz, SS officers transported Erna and approximately 530 other Hungarian Jewish women to Lippstadt, Germany. There, at a slave-labor camp in the Buchenwald complex, Erna made hand grenades and aircraft parts with other female prisoners. On Christmas, they decorated a tree and exchanged gifts they cobbled together from waste metal smuggled out of the factory under threat of death.

By spring 1945, the Germans knew final defeat was inevitable. One night, at the end of March, Nazi soldiers marched Erna and other women prisoners toward Bergen-Belsen threatening to shoot them whenever they heard Allied troops. Nazis forced some 56,000 weakened prisoners to march because SS chief Heinrich Himmler ordered soldiers to march all able-bodied prisoners away from the front lines as the Allied armies advanced. Thousands of prisoners were shot or died of cold, hunger, and illness in these death marches.

When Allied troops got closer, Nazi guards abandoned Erna and the other women close to the village of Kaunitz, about nine miles from Lippstadt. A few hours later, American soldiers liberated them. It was the morning of April 1, 1945.

Easter Sunday.

WHEN SHE WAS STRONG ENOUGH, Erna returned to Pécs, which was under Soviet occupation.

Rose and her husband, Marcel Stein, had previously returned to Pécs with their children, Anna and Gábor. They had survived the 1945 siege of Budapest. Anna remembered seeing friends and relatives shot in the Danube. When they moved back into their home in Pécs, most everything was gone—looted.

Anna remembered Erna returning to Pécs to live with them. Erna was the only camp survivor to return with a full head of hair. Anna watched as Erna began making sculptural reconstructions again in their home. Dinosaurs, this time. Maybe she’d had enough of humans.

The Hungarian government had already nationalized the family factory, claiming their businesses, houses, and properties, just as the Nazis had done. They also required the Steins to pay compensation to 150 workers.

Erna bought the family home from the Steins, though I don’t know how she got the money. The Steins used the money to pay the workers. Then they left, financially ruined. Marcel, Rose, and Gábor emigrated to New York. Anna went to Paris.

Meanwhile in Canada, Erna’s sister Margit searched to find Erna work so that she could emigrate. The Vancouver City Museum invited Erna to take a position there.

Before she left Hungary, Erna hosted a final exhibition of her work in the family home. At this event, she proposed that the city use the space as a natural history museum—opening it up to the very people who had betrayed her and sent her to her death.

Erna was not seeking revenge or retribution, though she had every right to. She opened her home and her heart, instead.

After Erna left for Canada, the Engel-Jánosi family home became a youth club, then a museum. Now it’s a tax office. Erna’s statues were destroyed.

She survived the worst genocide of the twentieth century. Her art did not. But I would learn that the Nazis’ campaign of cultural genocide across Europe was not the only reason.

Erna’s Complicated Legacy

IN CANADA, ERNA DIDN’T grow bitter. She grew flowers. She also looked for ways to help in her new country. Living with her widowed sister, Margit, Erna reconstructed herself again. She became curator of the Anthropological and Paleontological Department at the Vancouver City Museum.

But today, most museums do not show what’s left of Erna’s work.

When I visited the Kunsthistorisches Museum in Vienna in 2011, I asked to see Erna’s sculptures. Two separate museum officials said the statues and busts did not exist there, and that further, there was no record of Erna having worked at the museum. I did not know then what I know now. After 1935, museum officials removed Erna’s statues from their shelves because she was Jewish. This, I knew. What I did not yet know was that years later, long after WWII, officials at museums that held her work removed it again—this time because it was culturally insensitive.

When she was in Vienna in the 1920s, Erna had collaborated with anthropologist Egon von Eickstedt on her most famous sculptures of early hominids; to produce them, she joined her creative and mechanical talent to Eickstedt’s theories of ethnology. In the 1920s, before he came to Vienna, Eickstedt worked with Eugen Fischer, later a prominent Nazi scientist. With Fischer, Eickstedt dissected human corpses to study racial types. Eickstedt had access to fourteen preserved heads of “Melanesian” individuals from the German Pacific colonies. He took it upon himself to dissect the noses, taking measurements to investigate their relevance for racial anatomy. These measurements informed the thicknesses of the soft tissue layers that Erna applied.

While Erna was at Auschwitz, Eickstedt became famous for his 1934 book, Rassenkunde und Rassengeschichte der Menschheit (Racial Sciences and Racial History of Mankind), in which he attempted to classify racial groups using terms such as subspecies and subvarieties.

Eickstedt had the more robust scientific training of the two, and in the course of her collaboration with him, Erna embraced his theories as an intellectual basis for her work in scientific reconstruction. But for all she suffered and lost during the Holocaust, which was sometimes justified by its perpetrators using the high-minded language of theories such as Eickstedt’s, Erna did not rid herself of her former colleague’s ideas after the war.

Eickstedt believed that the aim of sculptural reconstruction was to produce a “racial portrait” that would convey the essential features of the subject’s “racial type.” “A reconstruction from a cranium depicts not the individual features of the man, but only those of the racial type to which he belonged.” But that last sentence is not Eickstedt’s—they are Erna’s words, as quoted by a museum in Vancouver that holds but does not exhibit her work.

Some of Eickstedt’s theories remained popular for decades after the Nazis lost the war. Erna’s belief in them would not have put her completely out of step with most other anthropologists during her life. But now, her use of those theories is, understandably, taken to compromise the work. As with Boule’s tendentious reconstructions of the Neanderthal as subhuman, Erna’s reconstructions of early hominids have been found to rely on false premises. They do not allow us to see everything that was true about their subjects.

But in Canada, Erna was also free again to ply her talents in other areas. Something must have clicked one day in 1953 when she read in the newspaper that Vancouver police had found the skeletal remains of two young children in the woods. She was 65. She called the police station and asked if she could help. She volunteered, molding busts from the buried bones. It must have been gruesome work, but she saw it through, knowing how important it was to try to tell the stories of two murdered children. Using her artistic and scientific skills in forensics, Erna gave voice to the silenced dead.

Erna’s busts are in the Vancouver Police Department’s museum. Almost seven decades after they were murdered, the victims’ identities were revealed with the help of DNA testing—a novel scientific approach making good on the promise of Erna’s sculptures: that human ingenuity could make it possible for the children to still be named, identified. Remembered.

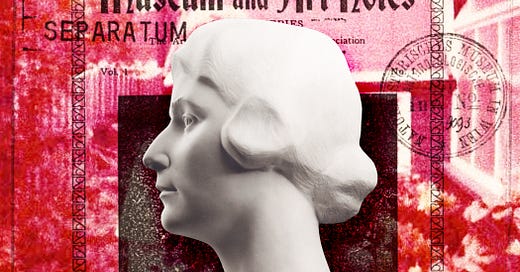

Erna had been living in Canada for four years when she wrote an essay titled “The Method of Reconstructing Human and Animal Remains in Sculpture and in Paintings” for a periodical called Museum and Art Notes. The cover of the issue was illustrated with a photograph of one of her dinosaur reconstructions, and her essay opens with an evocation of the joys of her line of work:

To the reconstructionist, the work of resuscitating a world which has completely disappeared in the infinity of centuries or millennia is so beautiful a task not alone from a scientific standpoint, but also from one of artistry, that it awakens the artist’s fullest enthusiasm. For him there can be no aim more glorious than to conjure up a true picture of that life which roamed the face of the earth millions of years ago!

Beautiful, artistry, enthusiasm, glorious, life. Those are the words this Holocaust survivor uses to describe her work.

To my knowledge, Erna never wrote about, sculpted, or painted what she witnessed or experienced during the war.

She died July 30, 1970.

She lives on through her granddaughter, Anna Stein, also an artist. Anna’s anthropomorphic figures in her paintings and stained glass are influenced by history, poetry, myth, and by the members of her illustrious family. Like me, Anna reconstructs her own dead.

The Afterlives of the Engel-Jánosis

ERNA RECONSTRUCTED HERSELF. So did my grandfather, my mother, and Anna. That’s how they survived, but also how they survived the surviving.

My grandparents moved back to Vienna around 1959, though the family home had been bombed twice by the Allies. Friedrich didn’t get the red-carpet treatment he’d hoped for, and he had to work out the messy details of becoming an Austrian citizen again. He didn’t get the full pension or salary of a full professor, so he continued teaching at the University of Vienna past when he would have liked to have retired.

My grandmother Carlette died soon after they moved. Heartbroken, my grandfather remarried to a woman not much older than my mother. Later, he wrote and called my mother to complain. He said he’d made a mistake. My mother told him he’d taken a vow before God. He was Catholic. Divorce was out of the question.

After Friedrich left her behind in 1939, Friedrich’s mother, Marie, hid from Nazis in a farmhouse in Czechoslovakia. She stayed there throughout the war, occasionally taking walks in the woods. One day, a Nazi soldier stopped her and demanded to see her papers. She said she’d left them at her house. The truth was that she had no papers. The Nazi soldier looked at my Jewish great-grandmother and concluded she couldn’t possibly be Jewish. Her eyes were too blue. He let her go.

When the war ended in the spring of 1945, Marie walked miles through snow to a Red Cross tent. She lost three toes to frostbite. She made her way to Washington, D.C., where she joined her son, daughter-in-law, and granddaughter—my mother. On their first Christmas together, Marie dragged Friedrich’s Christmas tree out to the curb.

When Marie celebrated her hundredth birthday in Washington, she let me read the congratulatory letter from Richard Nixon, whom she did not care for.

I was with her when she died. She was 105, and I was 16. I prayed alongside her rabbi. She only returned to Vienna to be buried in the family cemetery.

AFTER MY MOTHER DIED, I discovered her Kinderausweis, her parents’ Reissepasses, their visas, letters, baptism certificates, and papers in a box in her linen closet. She never discussed what was in this box.

Six different border guards stamped my mother’s Kinderausweis with swastikas before she eventually crossed into Switzerland and, eventually, freedom. Six different individuals.

But for every swastika stamp and Nazi signature kicking my mother out of Austria, there was a British, Swiss, French, or American official who also stamped or signed her pass, letting her in.