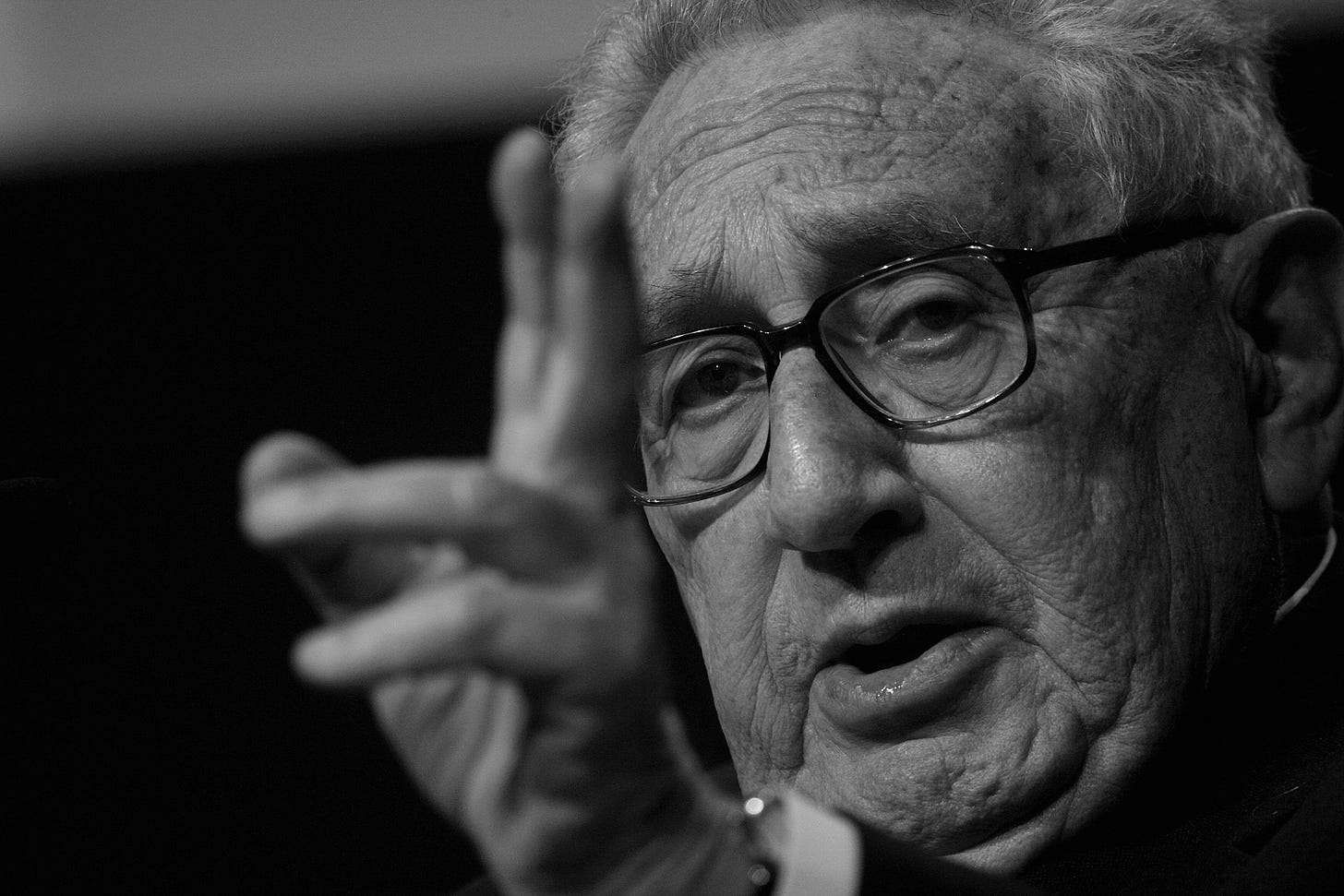

Remembering Henry Kissinger

The hugely important—and hugely controversial—former secretary of state has died at 100.

[Editor’s note: Henry Kissinger, the former secretary of state and national security advisor, died on November 29 at the age of 100. In a recent episode of The Bulwark’s podcast Shield of the Republic, cohosts Eric Edelman and Eliot Cohen discussed Kissinger’s life and legacy as a scholar of history and international relations, as a senior diplomat and statesman, and as a person. The transcript below has been edited for length and clarity; the full episode can be found here.]

Eliot Cohen: There do seem to be two very different ways which Kissinger gets treated: either as an extraordinary sage who delivered pronouncements from a foreign-policy Mount Olympus, or as a war criminal, duplicitous, conniving, underhanded—you pick your adjective. And I think both of us would reject both of those views since we don’t always agree with him but I think we do have a high regard for him. . . .

One of the things I think people miss about Kissinger is—well, two things maybe that they miss about him. One is a deep-seated patriotism—the kind of patriotism that only a refugee immigrant has, and which is a really critical part of his persona. That I think gets underplayed. And the second thing is his sensitivity. If you go look at White House Years, there’s a very poignant description of a meeting with a bunch of his fellow professors at Harvard. I think this is during the Cambodia bombing. And you know, some of those were the guys who got us into Vietnam for crying out loud. And he describes a meeting in which there are a lot of kind of caustic remarks, and it’s clear that this left him deeply wounded. . . . It left scars, and those scars are not fully healed even today.

Eric Edelman: Henry has been nothing but gracious and extremely nice to me personally. And I agree with you. Although I’ve met a number of people in Washington who are concerned about their reputation, I’m not sure I’ve met anybody quite as concerned about it as he is.

There are these dueling kind of images of Henry, and some people who have worked for him have recently come out excoriating him, which seems to me to be very bad form as he is essentially beginning to fade away. I have a lot more sympathy than I once did for the difficulties he faced trying to extricate the United States from Vietnam. I find the criticisms of people like McGeorge Bundy and others who got us into Vietnam and then turned on Henry to be somewhat disreputable.

On the other hand, he had the misfortune of serving one of the most paranoid presidents we’ve had. (I would have said ‘most malicious,’ but he’s now been surpassed in that category.)

Cohen: He lost that contest a while back.

Edelman: But look, it must have been really hard to work inside the Nixon White House, which suffered from all sorts of dysfunctions having to do with Nixon’s personality.

Cohen: And the people around him, too—the White House is never just the president—some of them duplicitous, scheming, backstabbing. And Kissinger was thrown into the mix of it.

Just to reinforce your point about the difficulty of extricating ourselves from that war, people now view his talk about a “decent interval” [between the withdrawal of American forces and the North Vietnamese conquest of South Vietnam] as cynical. Actually, there was something to it. He was concerned about America’s reputation, he understood that reputation is part of the currency of power. They’re dealing with a horrific domestic circumstances. . . .

Edelman: One can criticize Henry and Nixon for some of the duplicity of the negotiations they were involved in, although it’s really hard to be too critical given what we now know about the North Vietnamese, which is that they had no interest in negotiating at all—zero. And that’s been revealed from the North Vietnamese records. I do think he and Nixon gave away too much to Mao and Zhou Enlai in 1972, and I do think some of our problems with Taiwan today are a result of not quite as much attention to detail in the Shanghai Final Communiqué from that summit as there should have been.

But overall, I agree with you. I think Henry was motivated mostly by a desire to preserve America’s reputation and to get us out of a terrible war that was tearing the country apart.

I think he also grossly oversold détente with the Russians to the American public, which then created all sorts of problems later because the strategy that he and Nixon had of entangling the Soviet Union in a web of interlocking agreements really did nothing to constrain Soviet behavior around the world. In fact, it convinced the Soviets in the mid- to late-’70s that they were playing a winning hand. But these are details, as Henry would say.

Cohen: I think there’s a larger issue which really goes to the heart of his conception of foreign policy. In a certain way . . . he’s actually not enough of a realist. There is a somewhat romantic idea of great power politics as deals that are done by eminent statesmen at the top—although there’s a lot of attention to the deep historical currents underneath, which he’s absolutely right to focus on and which he can sometimes characterize brilliantly—but still, it’s a somewhat romantic notion. So you don’t have a sense that he’s actually looking there to really do the Russians in or do the Chinese in or just say, ‘Yeah, they’re a gang of cutthroats and murderers. They’ll come back at us once they’ve taken advantage of whatever it is we have to give them.’ And I think that helps account for his continued engagement with Putin and a whole series of Chinese leaders—not out of corrupt motives, but because he thinks that ultimately, this is about “serious people,” a favorite phrase of his, having serious discussions, coming to understandings. I think, unfortunately, for the world we live in, that’s not hard-edged enough.

Edelman: I think we tend to forget how young Henry was when he became national security advisor. He was 45 in 1968, and he came to it without any previous job in government. . . . His achievements are truly remarkable given the lack of experience that he had when he came in. . . .

Cohen: If you read the memo that he wrote to Nixon on the organization of the NSC staff . . . I first read it carefully after I’d been in government. I said to myself, ‘How did somebody who’d never actually served in government and had a sense of what things are like—how did he come up with this this brilliant piece of writing?’

The other thing which I give him enormous credit for: He had a great eye for talent. And he brought in people who would disagree with him. He wasn’t easy to work for, apparently. . . .

Edelman: I’ve heard that I’m good authority from many people who did work for him.

Cohen: But he had people who did not share his views. . . . There’s something impressive about that. . . .

Edelman: My biggest problem with Henry’s kind of realism is—it takes its root in his brilliant study of the Congress of Vienna in 1814–15. And the world is no longer made up of multinational empires with monarchs who are related to one another and speak a common language. . . .

There’s a real underestimation of two things: ideology and how it affects perceptions of national interest, and also the nature of regimes. Putin is not an ordinary statesman. . . . In Putin’s case, there’s both an ideological and a criminal enterprise element of this. Russia is run like a criminal enterprise. And I don’t think you can negotiate internationally with those kinds of regimes in the same way that Castlereagh, Metternich, Czar Alexander, and Talleyrand negotiated about the future of Europe. . . .

Cohen: You have to be impressed by [Kissinger’s] endless curiosity. And, you know, he’s continuing to write books at a well beyond the age where I intend to be putting pen to paper. And look at this latest fascination with the implications of AI. . . . You have to admire somebody who, in his late nineties, plunges in like that. The other thing is, I will confess I am charmed by his sense of humor. I know it’s used self-consciously—I think particularly self-deprecating humor usually is by prominent people as a way of disarming people. But it’s genuine. It’s always been there. That sort of sense of humor, whatever the size of their ego, whatever you agree or disagree with, it does indicate some sort of sense of proportion about how one views oneself. And, you know, I give him a lot of credit for that. . . .

Edelman: I do think it’s interesting that he seems to have revised some of his views about Putin and about the conflict in Ukraine, and I think that’s to his credit.

Cohen: Yeah, I think more than he has about China.

Edelman: Therein lies a problem. You made the comment that you think his views on Putin and China are not from corrupt motives, and I don’t necessarily disagree with that. But on the other hand, he has gotten very wealthy as a result of his work at Kissinger Associates. I think it has made it harder to disentangle his views on these subjects. Ultimately, that’s a question historians . . . will have to wrestle with as they complete the story of his incredibly long and fascinating life.

Cohen: Realists, of course, in theory, should think of states somewhat detached from individual personalities. I think once you’ve been in those positions though, there is an undeniable rush about being invited, as he used to be on an annual basis, to fly to Moscow in private jet just to have dinner with Vladimir Putin, or whenever you want to visit China, you can be sure that you’re going to meet with people at the absolute top. I think you wouldn’t be human if that didn’t go to your head somewhat.

Well, he’s an endlessly fascinating, complicated human being.