Revisiting Casanova After #MeToo

A new biography reveals the man whose name is synonymous with seduction was more depraved, but also more complicated, than usually believed.

Adventurer

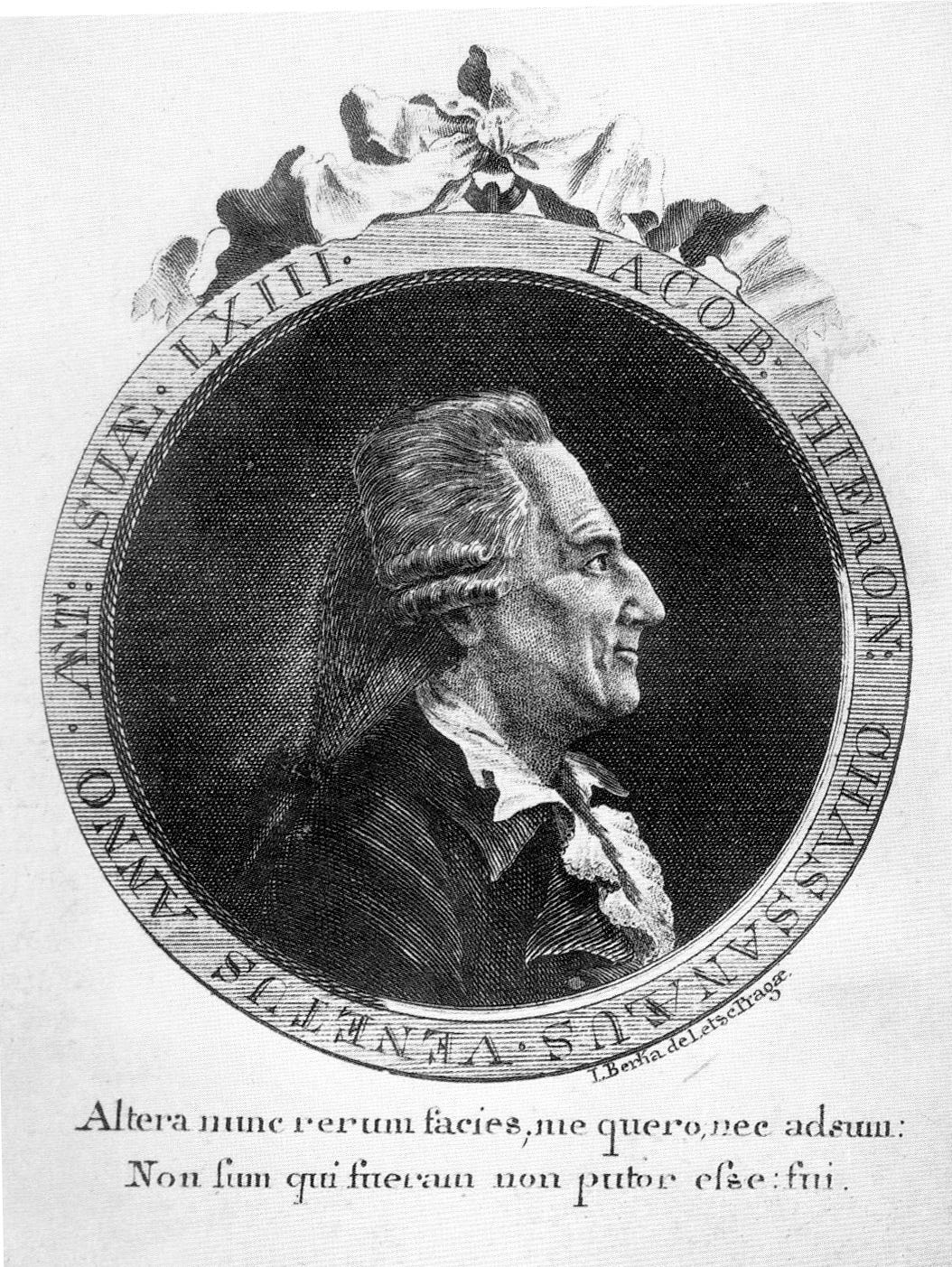

The Life and Times of Giacomo Casanova

by Leo Damrosch

Yale, 422 pp., $35

FEW FIGURES IN WORLD HISTORY are as iconic as Giacomo Girolamo Casanova, one of a select group whose names have become synonyms for “womanizer.” And yet as historical figures go, one could argue that Casanova, the eighteenth-century adventurer and memoirist, is an extremely minor one: His existence had little effect on the course of history, and his biggest contribution to culture in his lifetime was to have devised the state-sponsored lottery. Still, Casanova continues to fascinate. His autobiography, Histoire de ma vie (“The History of My Life”), has gone through some four hundred editions in twenty languages; France’s Bibliothèque Nationale acquired the original French-language manuscript (along with other Casanova documents) in 2010 for $9 million, its single most expensive acquisition ever. The memoir has also provided source material for numerous films, notably including Federico Fellini’s 1976 Casanova and a heavily fictionalized 2005 feature starring Heath Ledger.

Casanova’s Histoire was scandalous when first published in the 1820s, even heavily bowdlerized, and soon ended up on the Catholic Church’s index of prohibited books. Back then, it was condemned for its irreverence toward religion and frank depiction of illicit sexual adventures, some of them with nuns. In the 2020s, Casanova scandalizes for a very different reason: In the age of #MeToo and of acute feminist awareness of male sexual abuse of women, a man known primarily for his seductions is liable to be, as they say, problematic—especially when those seductions took place in an era of legally entrenched male dominance and often fuzzy notions of consent. When a Casanova museum opened in his native Venice in 2018, the Huffington Post reacted with an article titled “The Real Casanova Wasn’t A Ladies Man, He Was A Rapist.”

Adventurer, the new book by Leo Damrosch, an emeritus professor of literature at Harvard, self-consciously strives to be a Casanova biography for modern times: The first four pages of the introduction are essentially a #MeToo disclaimer. “Sometimes his behavior was abusive in ways that are not just disturbing today, but would have seemed disturbing to many people in his own day,” writes Damrosch.

Casanova did value his partners’ individuality, and he genuinely wanted to share mutual pleasure with them. But the balance of power was always unequal, and every one of his relationships was short-lived. . . . To hear him tell it, desire was always mutual and relationships always ended amicably. But even in his own telling, it’s obvious that some women got involved with him against their better judgment, and were regretful or bitter afterward.

And yet Damrosch insists that there is much more to Casanova, sexually and otherwise. For one, “The mutually gratifying encounters helped him to write eloquently about sexual experience in a way that was unique in his own time and has rarely been equaled.” Moreover, sexual encounters apart, his memoirs invoke an “invigorating” range of human experience—from music to occult experimentation to fine cuisine: “Over two hundred meals, often shared with lovers, are affectionately recalled in what has been described as his ‘gastrosexual journeying.’”

The story of Casanova’s life reads like a picaresque novel—which, as Damrosch reminds us, is a quintessentially eighteenth-century genre. The hero is forced to fend for himself from an early age; seeks out a promising career that soon gets derailed; crisscrosses the world; is unjustly imprisoned and carries out a near-impossible escape that makes him a celebrity; falls passionately in love with a mysterious stranger who leaves him after a short, blissful time together, and whom he almost meets twice more; makes and loses a fortune; has a string of bawdy and occasionally romantic encounters; and is finally left to ponder the lessons of his adventures as a lonely old man enduring the indignities of age compounded by indigence and dependency on wealthy patrons.

CASANOVA WAS BORN IN 1725. Venice at the time was an infamously libertine city where sexual license flourished along with gambling and other vices, and religion was more about decorum than devotion. Giacomo was the first of six children born to two actor parents. A quick-witted but morose and sickly boy (memorable early experiences included being taken to a witch to cure persistent nosebleeds), he was sent away to a boarding house in Padua at the age of 9 for his health and schooling; he experienced it as a final rejection by already-absent parents. “Ce fut ainsi qu’on se débarrassa de moi,” he writes in his memoirs, a phrase Damrosch translates as “It was thus that they got rid of me”; but with the impersonal French on (of which Damrosch takes note), it is perhaps best conveyed as “It was thus that I was cast off.” The bitterness is palpable.

In Padua, Giacomo started university classes at the age of 12 and his erotic education at 11, at the hands of the 13-year-old niece of the tutor with whom he lodged. The girl, Bettina, had gotten into the habit of sitting on Giacomo’s bed to comb his hair and wash his face and chest. On one occasion she decided to wash his legs and, as Casanova puts it in his euphemistic way, “carried her zeal for cleanliness too far.” Shaken and confused, the boy believed he had “dishonored” Bettina and had to repair the damage by marrying her. (Such impulses would be quite alien to the adult Casanova.) Later, he sat by her bedside when she contracted smallpox and nearly died; Bettina declared her love to him upon recovery, but went on to marry an older man.

At 14, Casanova returned to Venice where he began to train for an ecclesiastical career and found a rich aristocratic patron; the following year, he lost his virginity in an encounter with two sisters. The ecclesiastical career didn’t work out: After a year in Rome as an aspiring priest and private secretary to a cardinal, 19-year-old Casanova got embroiled in a scandal and had to make an abrupt departure. By his own account, his offense was helping his French tutor’s daughter elope with her lover; another version is that he stole a mistress from the Pope’s nephew.

THUS BEGAN Casanova’s life as a wanderer. His travels took him to dozens of cities including Istanbul/Constantinople, Paris, Geneva, Zurich, Vienna, London, and Moscow. (He tried to sell George III and Catherine the Great on his national lottery idea as he had successfully done with Louis XV, but failed in both cases.) His occupations were almost as varied as his domiciles: He was, Damrosch tells us, “a naval officer, a theater violinist, an entrepreneur, a professional gambler, a practitioner of magic, a novelist, a spy, and a con man.” To this list, one could add translator (he published a translation of the Iliad in rhymed couplets), journal publisher, actor, playwright, theatrical producer, financial consultant, essayist, pamphleteer, and secretary to an ambassador. Casanova’s career successes almost invariably foundered on lack of discipline; he blew his money as quickly as he made it and often ended up mired in debt. When, on a trip to Geneva, he visited the aged Voltaire in an attempt to prove himself as an intellectual, the results were disastrous; feeling spurned by his onetime idol, Casanova, who had a nasty streak when his vanity was piqued, published several critiques attacking Voltaire as a fanatic, a fame hound, and an unoriginal thinker. He later expressed regret in his memoirs.

In a sense, “con man” was, for Casanova, not just an occasional occupation but an essential trait. At a certain point he began to pose as an aristocrat, styling himself the Chevalier de Seingalt or the Baron or Count de Farussi (his mother’s maiden name). He also ran some literal scams, one of which, Damrosch remarks, would be highly entertaining in a novel but poses a clear “ethical challenge” for Casanova’s defenders in real life. It involved bilking an aging French noblewoman, the Marquise d’Urfé, out of vast amounts of money by playing to her obsession with the occult and her fear of death.

Casanova managed to convince the marquise that he could transmigrate her soul into a male infant he would father. The role of surrogate mother was initially assigned to a female confederate; when she proved unreliable, a new plan was hatched, calling for Madame d’Urfé to incubate her own reincarnation after ritual sex with Casanova. (To ensure that the magus was up to the task, his then-mistress cavorted nearby playing a naked spirit.) Along the way, Casanova relieved the marquise of some very expensive jewelry, supposedly to be tossed into the Mediterranean as a sacrificial offering. Eventually, a disgruntled ex-accomplice exposed the scheme, and the magus had to make a quick getaway; some years later, a public confrontation with the old woman’s grandson led to Casanova’s permanent expulsion from France.

When Casanova felt wronged or insulted, his temper could manifest itself in nasty ways, including physical violence. It helped that he towered over most of his contemporaries—he was about 6-foot-3 when the average European adult male stood just over five and a half feet tall—and that law enforcement was haphazard. (In one telling episode, Casanova badly thrashed a servant who was running a con of his own, claiming to be a duke in disguise. Casanova beat the man and then had to lie low for a few days, fearing trouble with the law; not until the “duke” was unmasked as an imposter was Casanova in the clear.) There’s also a disturbing revenge prank involving the sawed-off arm of a cadaver, somewhat reminiscent of the famous “Need a hand?” scene from Young Frankenstein, except that the terrified victim had a stroke and apparently remained “stupid and spasmodic” for life.

As for Casanova’s sexual transgressions, some will appall even the most tolerant—such as sex with barely pubescent 11- and 12-year-old girls who were being prostituted by their parents. Such incidents, Damrosch says, occur in Histoire regularly enough to suggest “pedophilia,” if we may use a label from our own day. It is possible that some of Casanova’s petites filles were older than he reported: As Damrosch notes elsewhere, instances in which his partners can be identified show that he often shaved a few years off their ages. Nonetheless, the sexual exploitation is undeniable and indefensible, reaching an “ugly nadir” when, on his trip to Russia, the 40-year-old Casanova bought a 13-year-old serf—i.e., de facto slave—who was explicitly being sold for sex. Casanova, who gave the girl the exotic nickname “Zaire” and taught her some Venetian Italian, insists that he didn’t treat her as a slave and portrays her as not only a willing lover but a violently jealous one. Of course, we have no way of knowing what “Zaire” really felt; but there is little doubt that, as Damrosch says, Casanova romanticized the situation to camouflage its essential ugliness.

And then there’s the episode in which a woman in Venice accused Casanova of raping and beating her daughter. In his response, reproduced in full in the memoirs, he angrily denied the rape and explained that he had spanked the girl with a broomstick because, after he paid the mother for sex with the daughter, the girl (age unknown) wouldn’t cooperate. Casanova was genuinely indignant about the complaint, which forced him to skip town, and apparently had zero awareness of how terrible his defense made him look.

SO FAR, SO BAD. And yet a summary dismissal of Casanova as “an abuser,” as in the 2018 Huffington Post article, is as simplistic as the “world’s greatest lover” mythology.

While Damrosch’s unflinching chronicle prompted the anonymous reviewer for the Economist to assert that “the nature of [Casanova’s] conquests usually discounts any notion of mutuality or consent,” this is a drastic overstatement. Yes, on some occasions—even with adult women—Casanova assumed consent where reluctant acquiescence seems the more likely explanation; but in general he sought not just willing but enthusiastic partners. Unlike, say, the fictional Valmont of Les Liaisons dangereuses, the Casanova of Histoire de ma vie does not pursue elaborate seductions or relish the challenge of coaxing an initially unwilling woman into surrender; most of his liaisons are based on mutual desire and mutual initiative from the start.

Damrosch, who is nothing if not critical of his (anti)hero, stresses that Casanova held a strongly egalitarian view of sexual pleasure and that his ideal sexual encounter was a meeting of minds and spirits—and a dissolution of boundaries that could transcend sexual division. At one point, describing a night he spent with two women, Casanova writes that “all three had become a single sex.” Damrosch quotes French psychoanalyst Lydia Flem: “At the moment of supreme pleasure, distinctions are obliterated. Casanova sees himself as having the same sex as his partner or her as having his; he no longer knows to what gender he belongs.”

If this sounds remarkably “genderfluid” (in modern parlance), that’s because Casanova’s writings often are. He delighted in sexual ambiguity. Two of the enduring loves of his life, the singer Teresa and the aristocratic adventuress Henriette, were cross-dressing when he first met them; Teresa, who was posing as a castrato because women in Rome were then barred from singing in public venues, even perfected her disguise with a crude rubber penis affixed to the skin with gum. Many of Casanova’s lovers were bisexual; he also matter-of-factly describes two sexual experiences with men, and mentions more in margin notes.

The romance with Henriette is the closest Histoire has to a timeless love story. When Casanova met her in 1749 at an inn near Milan, she was traveling with a Hungarian officer, herself in an officer’s uniform that did not disguise her sex very effectively. Soon, Casanova, then 23, was madly in love. He declared his feelings and asked her to make a decision: Did she want to leave the Hungarian and travel with him? When the young woman laughed at his bluntness, he gave (by his account) a remarkable reply:

The word “decide” shouldn’t seem harsh to you. On the contrary, it honors you, since it makes you the arbiter of your fate, and of mine.

Henriette said yes, and they went to Parma and spent three rapturous months together. Casanova was smitten not only by her beauty, charm, and elegance—by then, she had returned to female clothing—but by her keen and cultivated mind and her talents; among other things, she was a superb cellist. (Interestingly, his accounts of their lovemaking are, by his standard, unusually discreet.) He also learned that she was married and on the run from an abusive husband and father-in-law who had threatened to lock her up in a convent for infidelity.

The happy interlude ended abruptly when Henriette was recognized by a relative who may have been sent to track her down, and agreed to write to her family to negotiate a return home. At an inn in Geneva, she said good-bye and scratched a farewell message to Casanova on the windowpane with the small diamond of a ring he had given her: Tu oublieras aussi Henriette, or “You will also forget Henriette.” (He didn’t.) A subsequent letter asked him not to look for her and to let their time together remain “a pleasant dream.”

Years later, there were two near-encounters, in the first of which Henriette—now a widowed countess with a château near Aix-en-Provence—slept with Casanova’s then-mistress. (It was only after they left the château that the mistress handed Casanova a letter revealing their hostess’s identity.) The second time, Casanova—then in his late forties—finally wrote to Henriette after narrowly missing her in Aix, where he’d been getting treatment for pleurisy (and she, unbeknownst to him, had paid for his nursing care). She wrote back to say that she still loved him but would rather not meet: They had both aged, she had put on weight, and it was best to keep things as they were. They did correspond after that, though he burned all her letters at the end of his life.

The Henriette story shows Casanova at his best; but there were many other episodes in which he seems to have genuinely cared about his lovers. Sometimes, he encouraged or even arranged marriages that gave them security and status. In one revealing episode, Casanova falls for a lovely young woman he calls Cristina and asks her to marry him; after they sleep together, he gets cold feet (who’d’ve thunk it?) but is aghast at the thought of leaving a seduced and abandoned woman behind; thankfully she has a large dowry, and he easily fixes her up with a handsome and dependable fiancé. (It’s too bad Damrosch omits an even more telling detail: Once the wedding is on, Casanova starts to feel twinges of regret.) On a number of occasions he helped women who were in some sort of predicament, often involving a pregnancy or other man trouble, and was fully resolved not to take advantage of their vulnerable state—though sometimes sex eventually happened anyway.

WHEN DAMROSCH ISSUES harsh judgments, they are mostly warranted—but some of his conclusions founder on too much feminist theory. Is it really true that, given the institutionalized sexual inequalities in eighteenth-century Europe, the “power imbalance” always favored Casanova over his female partners? Then as now, power existed in many complex forms; class, for instance, mostly trumped sex. And, while women’s sexuality was certainly far more rigorously and punitively controlled, men who misbehaved with respectable women could pay a high price: Casanova’s contemporary and fellow libertine the Marquis de Mirabeau, the future revolutionary orator, spent several years in a dungeon under a death sentence for running off with another man’s wife.

In any case, Damrosch’s own narrative refutes his blanket claim in the book’s opening pages that in Casanova’s relations with women, he “had power over them” and “enjoyed exploiting it.” Certainly not with Henriette; or with another recurring lover, the highborn Venetian nun “M.M.”; or with Andriana Foscarini, a sea captain’s wife in Corfu who was willing to share passionate caresses but drew the line at intercourse, much to Casanova’s frustration. (The affair had a tragicomic, or perhaps tragi-farcical, ending: Just as Andriana decided to cross that line, Casanova contracted an infection from a local courtesan, and to his credit made a full confession.) Courtesans weren’t powerless, either: Near the end of Casanova’s sexual career, a young woman of that trade put him through a cat-and-mouse game that briefly made him suicidal.

Interestingly, Adventurer also makes the case that Casanova held remarkably progressive notions of sexual equality: In 1772, he published a pamphlet arguing that women had the same intellectual capacity as men and lacked only in training to develop their minds. The pamphlet, titled Lana caprina (“Goat’s Wool,” or something like “Woolgathering”), was written in rebuttal to a debate between two physicians one of whom maintained that women’s thinking originated in the uterus. The idea of Casanova as a feminist avant la lettre is certainly intriguing, but Damrosch gives short shrift to his contradictions on the subject. In the Histoire, a passage effusively praising Henriette’s wit—and more generally intelligence as an essential part of female attractiveness—is followed by an aside disparaging women who engage in serious scholarship: Such pursuits, Casanova opines, are not only unfeminine but pointless since women lack the vigor necessary for true intellectual achievement. But that’s not his last word, either: At a later point, a Swiss pastor’s comely niece, Hedwig, captivates him with her brilliant conversation on theology.

It’s hard to say how seriously Casanova took his own arguments in Lana caprina, which he says he dashed off to make fun of the physicians’ ponderous exchange. But ultimately, the likely explanation for these inconsistencies is simply that he was a man of paradox whose attitudes were at once radical and deeply conservative. He was passionately attached to (his own) freedom and independence but also convinced that, as he told Voltaire, the people needed to be “kept in chains” to be content. He chafed bitterly at the fact that the patricians of Venice would never recognize him as an equal, yet admired aristocratic privilege and was horrified by the French Revolution long before it degenerated into the Reign of Terror. Despite his sexual and philosophical libertinism, he also supported established religion, and even half-defended his own detention in Venice on ludicrous charges of devil worship. No wonder he also contradicted himself regarding women and sexual difference.

THERE IS NO QUESTION that a number of Casanova biographies have neglected or whitewashed the famous libertine’s unsavory side; to that, Adventurer offers a welcome corrective. Yet sometimes, it feels as if Damrosch is trying too hard to show that he deplores Casanova’s predatory actions and considers the victims’ perspectives. This prosecutorial approach can feel heavy-handed, and it’s likely to embolden rather than pacify those who believe “problematic” figures from the past belong on the dustbin of history. The reviewer in the Economist, for instance, concludes that Damrosch’s indignation at Casanova’s terrible behavior is inadequate and that the book gives no good reason “why readers should follow Mr Damrosch into the mud.”

But in fact, Adventurer—a smart and engaging book, quibbles notwithstanding—offers a vivid canvas of a fascinating era, viewed through the experiences of a remarkable man who was far more than the sum of his worst parts. However unsympathetic Damrosch’s Casanova may be at times, he contains enough multitudes, and has enough larger-than-life charisma, that it’s easy to see why this man mesmerized generations of readers of both sexes. (There is a striking cultural arrogance in dismissing his appeal as an outdated product of ignorance and sexism.) There’s also the fact that, as Damrosch makes clear, Histoire de ma vie is an extraordinary work: It may not be a literary masterpiece, but it’s a unique window into eighteenth-century life, a portrait unrivaled in its rich texture and immediacy.

In life, time was not kind to Casanova. He did not age well, even for that era; a life of excess, including sexually transmitted diseases and quack cures, probably didn’t help. He acutely felt the loss of his virility and sex appeal. His memoir breaks off abruptly before he hits 50: “In a real sense, when he was no longer young and charismatic, he was no longer Casanova,” comments Damrosch. His varied transgressions had gotten him barred from most European cities, and his business ventures failed. He spent his twilight years as librarian at Dux (Duchov) castle in Bohemia, now the Czech Republic, recreating his past in his autobiography (based on voluminous contemporaneous notebooks which, alas, he later destroyed) and bickering with castle staff about real and imagined slights. He died two years short of the century’s end, a relic of a bygone age, reclaimed by the obscurity from which he had once risen.

In the afterlife, history was much kinder: The publication, decades after his 1798 death, of his Histoire snatched Casanova out of obscurity again and propelled his memory to controversial stardom. Is his posthumous fortune running out, and will the age of social justice get him “canceled”? Not very likely; the Damrosch biography shows that Casanova’s story can still be riveting post-#MeToo. Meanwhile, the Casanova legend is so much a part of our cultural language that even the lyrics to Beyoncé’s new song “Alien Superstar” include a self-description as “Casanova, superstar, supernova.” The old rascal would have loved it.