WHEN THE CULT WRITER RICHARD BACHMAN died of cancer in 1985, he left behind four strange and angry novels about 1970s America (a couple of which were filtered through a mesh of soft science fiction), and one best-selling horror novel. The tumor was discovered in 1982, the year his penultimate novel The Running Man came out. The illness lends his next novel, Thinner (1984) an extra, unhappy jolt. But of course, dead though he was, Bachman, the writer, wasn’t done. Two more novels would be published posthumously: The Regulators (1996) and Blaze (2007). Both of these did better commercially than anything he’d published in his lifetime.

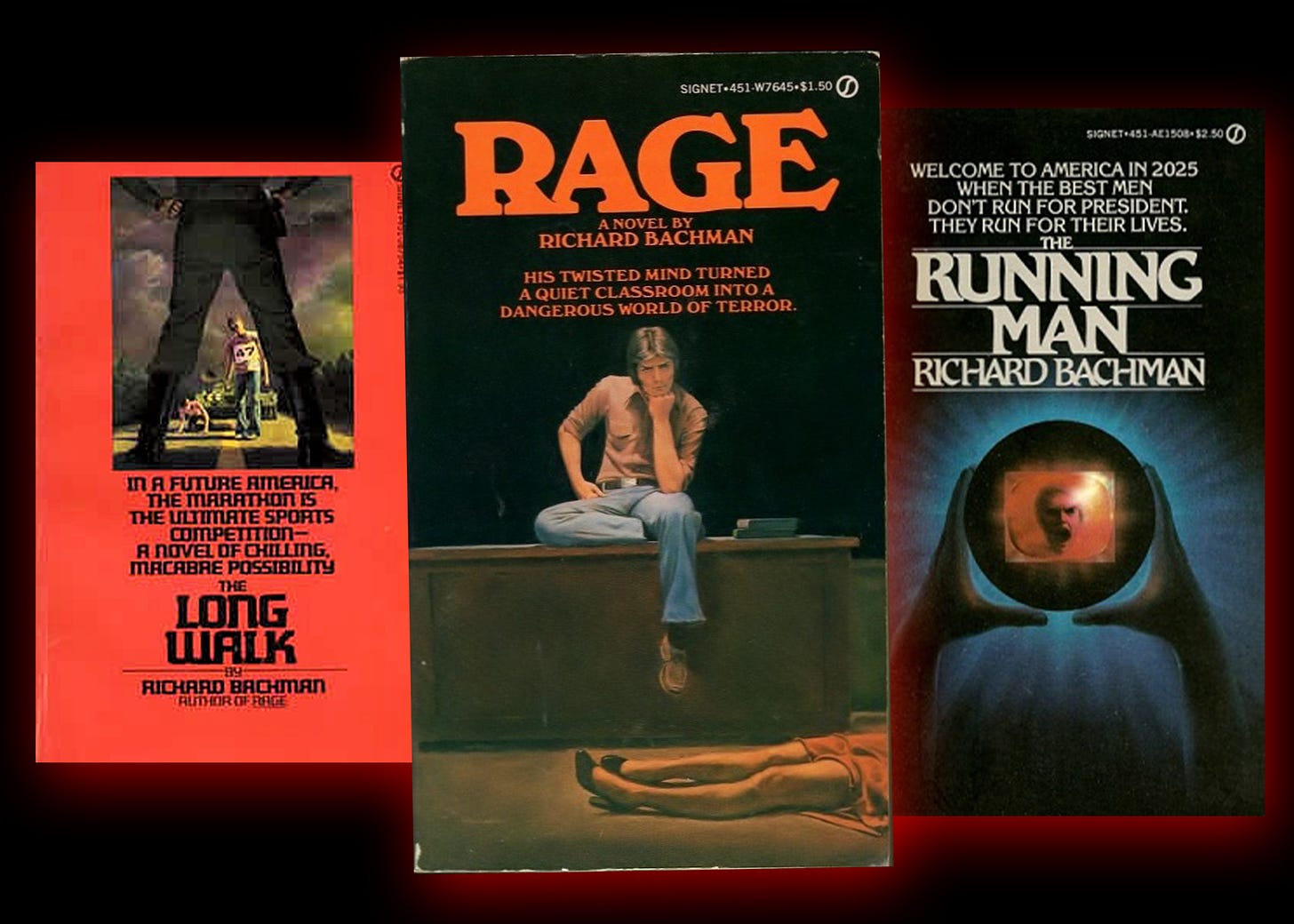

His first novel, Rage (1977), is an early fictional take on school shooters, not at that point the terrible phenomenon it would become. This perhaps explains Bachman’s rather trivial treatment of the two teachers murdered by our “hero,” Charlie Decker. Following these early acts of violence, Charlie takes a classroom of students hostage and talks to them about their lives and humiliations and feelings about school and the world, all the while holding off the cops with a kind of extravagant rudeness that I don’t think would work the same magic in real life.

Anyway, it must be stated bluntly and outright: Rage is a terrible novel. Bachman and the student hostages completely buy into Charlie’s radical horseshit, even though, as the one reasonable and moral student in the class points out over and over again, Charlie has already shot two innocent teachers to death. But they were teachers, therefore they were the Man, therefore their deaths don’t matter. That one reasonable student, a sympathetic, likable jock named Ted Jones, is actually the villain of the piece. When Ted is horribly abused by Charlie and the other students, and when his mother is revealed as an alcoholic against his wishes—which is, somehow, depicted as something he should be ashamed of—the reader is meant to feel satisfaction. Well, I didn’t. I wanted a police sniper to take Charlie’s ass out. In any case, when Bachman learned that Rage had inspired several school shooters, he took it out of print.

Bachman’s next book was The Long Walk (1979). Set in a vaguely science-fiction type of America (is it the future? Is this an alternate history?), the characters are, once again, mostly teenagers who, as the novel opens, are about to take part in The Long Walk, an annual, government-funded contest that involves a whole lot of walking, and will result in 99 out of 100 contestants dead, and one winner. The winner, supposedly, will take home the ultimate prize, which is anything they could ever possibly want. That’s what the government will give them. But you first have to get through days and days of constant walking, no sleep, hundreds and hundreds of miles, without committing the kind of rule violation that would result in one of the soldiers tracking the walkers from the sidelines shooting you in the head.

The hero of this novel is a kid named Garraty, though his status as protagonist seems to have been earned by his having the least, or most subdued, personality of any of the kids we get to know. Garraty’s walking with a lot of aspiring philosophers, of course, like Peter McVries, Garraty’s best friend on the walk. None of the conversations in The Long Walk that spring from deeper thoughts about life matter all that much. The ones that do matter, to me, are the ones among the walkers that are about why they are even doing this at all. Because The Long Walk is not something the government drafts people into—it’s something people have to volunteer for. So as the body count rises, the question of motivation bubbles up—in the kids’ minds, and in the mind of the reader. By book’s end, it remains an open question, which only makes the novel stronger.

With these two novels setting a kind of base, a student of Bachman’s fiction can find much overlap in the themes, and even the broad storylines, in these early books. For example, Roadwork (1981) has the same kind of non-genre fight-the-power menace as Rage. It is, however, much better than Rage. Generally speaking, I actually like Roadwork, but this is an unpopular opinion (Bachman aficionados are just as likely to criticize his work as they are to praise it). Roadwork is about a man who snaps when he learns that a new expressway will be built through both the large laundry he manages and his own home, meaning he has to move both. His self-destructive reactions to this fact ruin his marriage, and his life. This was Bachman’s idea of a mainstream, literary novel, though he grew to dislike it. In its favor, the book is blessedly free of teenagers, and it doesn’t back his actions all the way, as Bachman did for Charlie in Rage.

The last of these original four novels—and the best known, thanks to its adaptation into an Arnold Schwarzenegger film—is The Running Man, which takes and greatly expands on Bachman’s conception of The Long Walk. Here is another futuristic and fatal gameshow, for which the participants have to, more or less, volunteer. The novel’s place in science fiction is less ambiguous than that of The Long Walk: The Running Man is almost aggressively dystopian. Despite this, Bachman never begs us to love his protagonist, the surly, dour, humorless Ben Richards. The book’s morals are rather harsh, or even non-existent. The whole thing ends with a terroristic conflagration, and even then I think Bachman missed a trick by choosing to have Richards commit an act of decency before turning a chunk of America into Hell. For a variety of reasons, Richards, already a difficult man to like very much, should be long past acts of decency.

The Running Man is an angrier version of The Long Walk; Bachman’s disgust is more pointed. As a work of fiction, it’s still disappointing in some ways. While there are a few violent encounters with the police, of the Hunters—the team of trained killers hired by the TV network that produces the game show to track and execute Richards—there is almost nothing. It’s never settled if Richards even sees a Hunter, let alone does battle with one, or more. The 1987 film version, this is not. That’s a bad movie, but there’s a sense of fun about it. Though not a prerequisite for a novel to be good, some action that was less despairing might have been a good idea. Also, Bachman’s writing, though not bad and sometimes rather good, could occasionally miss the mark. Maybe this is nitpicking, but describing a building in The Running Man as “futuristic” when the story is already set in the future, is perplexing. What does “futuristic” mean to Ben Richards? Not the same thing it means to me, I’d wager.

While not much is known about Bachman’s life, what is known is significant. Particularly relevant is the death of Bachman and his wife Claudia’s six-year-old son in a freak accident. This would appear to inform not just parts of The Running Man and Roadwork (Barton Dawes, Roadwork’s protagonist, is still grieving the death of his son as the story begins), but also, perhaps, his turn towards horror in 1984. Which isn’t to say that Thinner, easily Bachman’s best novel, has anything to do with that real-life tragedy, but maybe horror began to seem to Bachman as the best way to channel his dark thoughts and feelings. Yet Thinner has a distinctly fun approach to the genre. In fact, Thinner is nothing if not a self-conscious return to the darkly funny and acidic morality tales as stylized by EC Comics and their Tales from the Crypt, especially. Briefly, an attorney—while receiving a sexual favor from his wife—runs over a gypsy woman. The attorney, Billy Halleck, is an enormously fat and arrogant man, who dodges a manslaughter conviction through unethical means. An older gypsy who was with the woman Halleck killed places a curse on Halleck—“Thinner,” the old man says to the attorney—and slowly Halleck begins to rapidly, dangerously lose weight. Upon figuring out what’s going on, Halleck takes steps to end the curse (with the help of his Mafia buddy, Richie). But in the end, he succeeds only in spreading the curse to his family, and finally resigns himself to death. Is this Bachman placing the blame for his son’s death on himself? Not only himself, but his wife, too? Thinner is fun, but punishing. While not a theme throughout, the novel ends on a note of hopeless grief, experienced by a man who it’s nearly impossible to like. Bachman’s anger, on clear display in those early novels, has at last turned inward.

After Richard Bachman died, from a disease that no doubt rapidly shed weight from his bones, two novels were published posthumously. First was The Regulators, a bizarre horror novel of a particular phantasmagorical kind; it features, among other things, the residents of a suburban neighborhood being regularly attacked, and routinely slaughtered one by one, by shotgun-wielding cowboys and G.I. Joe-esque soldiers. These attackers turn out to be created by the mind of an autistic child who is possessed by some sort of wicked demon. As I say, a bizarre novel, with a high body count: Characters the readers might expect to hang around for a while are unceremoniously blasted off the page. Though not completely successful (not at all successful, some might argue, but I found some value in it), it’s nevertheless a significant book in Bachman’s career, even if he’d died over a decade before the public laid eyes on it. He’d never written anything like The Regulators before. It combined the grim attitude of his early work with the fantastical extravagance of Thinner, but this time with an added, if tiny, bit of hope. If not for this life, then perhaps for the next.

Bachman’s final novel (so far?) was Blaze. It’s about a mentally challenged man who is stuck with the task of kidnapping the baby of a rich couple after his partner, George, is killed. George was the brains of the operation, but now he’s gone. What will Blaze do? The book is basically a crime novel by way of John Steinbeck. As alarming as that might sound, it’s not bad. It’s possible to empathize with Blaze while fearing for the baby he’s snatched. Again, here is the peril of a child, and I never felt confident that the baby would survive the ordeal (a young boy is the first victim in The Regulators, incidentally).

The rage that Bachman felt, and immaturely expressed in his first novels, remained with him throughout, but it also deepened, and even softened. What would he think now, a cult writer who gained more success after his death than before it? A dead writer who has somehow lived on.