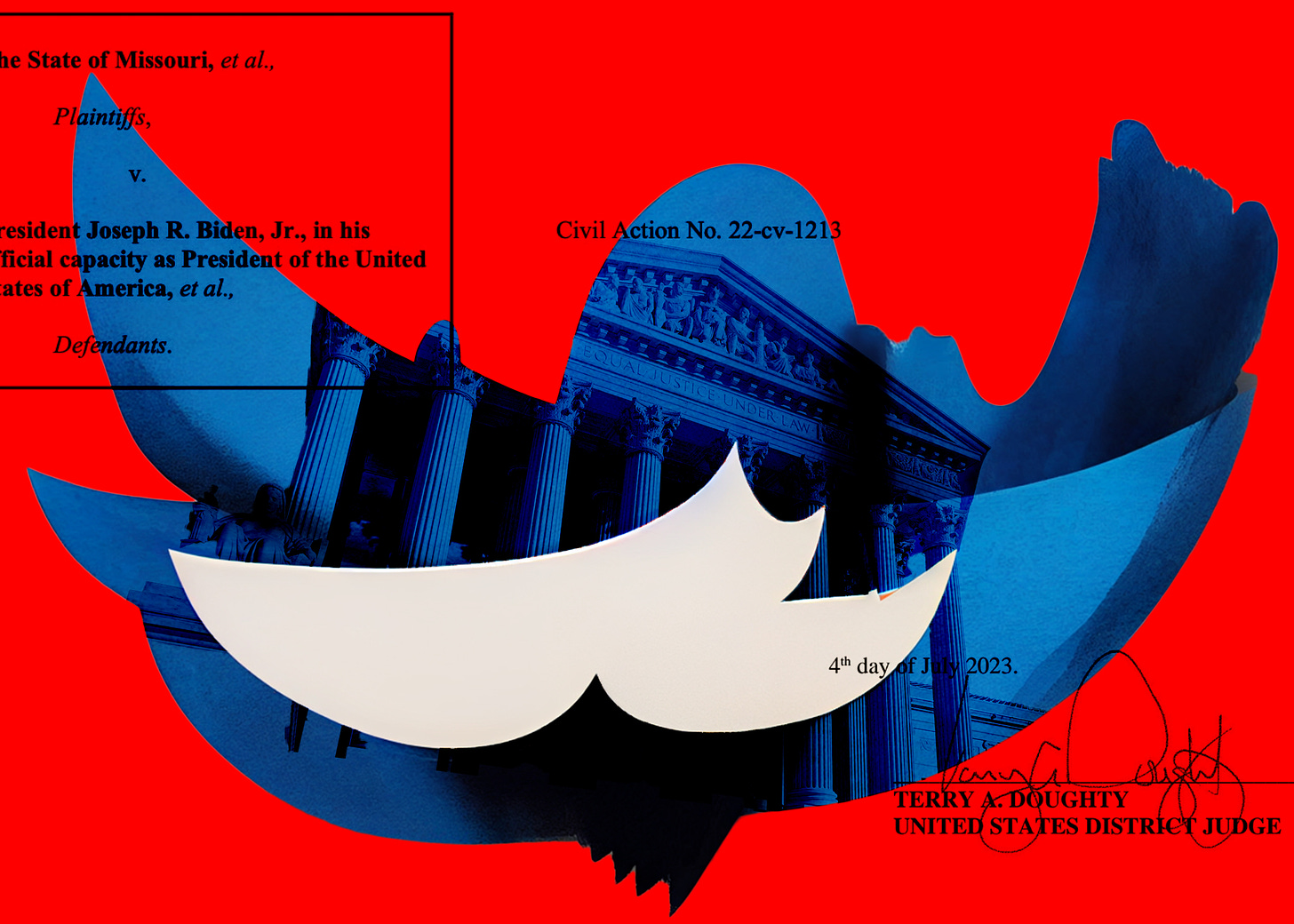

The Right-Wing Lawsuit That’s Forced the Feds to Stop Talking to Social Media Firms

A deeply flawed injunction in response to paranoia about censorship.

LAST WEEK, THE STATES OF MISSOURI AND LOUISIANA (along with a number of individual plaintiffs) secured a preliminary injunction prohibiting a host of federal agencies from communicating with “social-media companies for the purpose of urging, encouraging, pressuring, or inducing” the “reduction of content containing protected free speech.” The ruling temporarily prohibits the government personnel—specifically naming several White House staffers, the CDC, the FBI, the Department of Justice, the Department of Homeland Security, the Department of State, and a slew of other federal agencies, officials, and employees—from even speaking to Google, Facebook, Twitter, and other social media companies about misinformation online.

This is a big legal deal.

U.S. District Judge Terry A. Doughty, the Trump appointee who issued the injunction, carved out a few exceptions. The enjoined federal agencies can still communicate with social media companies about criminal activity, threats to national security or public safety, and criminal efforts to suppress voting through cyberattacks or foreign attempts to influence elections. They can also communicate with the companies about deleting or suppressing posts “that are not protected free speech”—although that only raises the very legal question that the injunction purports to address.

Politics is solidly in play here. In his 155-page opinion accompanying the order, Judge Doughty called it “quite telling that each example or category of suppressed speech was conservative in nature.” Particularly troubling to Doughty, for example, were the government’s efforts to purportedly “censor” posts that questioned the wearing of masks and vaccines during a pandemic, opposed “COVID-19 lockdowns,” and “showed two delivery vans driving to a building at 3:30 a.m. with boxes, which were alleged to contain election ballots” in Detroit, Michigan on election night in 2020.

Conservative Twitter and the state attorneys general who brought the suit were quick to rejoice in the injunction. And while, as critics on the center and left have pointed out, there are many glaring legal flaws in Doughty’s analysis, practically and politically speaking, they don’t matter much. The damage is done. The Biden administration has already reportedly had to cancel critical meetings. And millions of Americans perceive the ruling as a valid legal victory, which it is—at least for the time being, until it’s overruled by a higher court. (DOJ already filed an appeal to the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit.)

Still, for those who actually care about the law, here are five reasons why Judge Doughty’s order is a mess:

1. Missouri and Louisiana appear to lack standing to bring this lawsuit.

The judge claims in his opinion that the states are (patronizingly) acting as “parens patriae” on behalf of their citizens—a Latin phrase that literally means “parent of the nation,” as if good parents are those who protect the spread of lies with life-and-death implications for their children. Justice Brett Kavanaugh recently wrote a majority opinion rejecting Texas’s claim that it had standing to sue the Biden administration over its immigration enforcement priorities. The Fifth Circuit should apply his reasoning here.

2. The government has a measure of legal authority to regulate broadcasted speech.

George Carlin famously had a monologue based entirely on the “seven dirty words you can never say on television.” And the Supreme Court just sidestepped—without deciding—whether Section 230 of the Communications Decency Act, a statute passed by Congress, establishes liability for tech companies that post user content resulting in terrorist violence. Notice what it didn’t do: It didn’t apply some magical First Amendment precedent forbidding the government from regulating internet providers.

3. There’s a big factual question as to whether the government actually engaged in coercion rather than, well, just talking with the tech firms.

The court issued its ruling preliminarily—meaning it heard evidence to determine whether there’s a likelihood that the plaintiffs would ultimately prove and win their case. Doughty’s conclusion that the government showed “willingness to coerce” (rather than good-faith coordination with industry leaders in the midst of a global health crisis that killed millions) is highly dubious.

4. The district court took the preposterous position that Twitter, Google, and Facebook are controlled by the Biden administration.

Otherwise, it would be impossible to reach what is wholly private conduct by these social media companies. Doughty properly cited the law here, which holds that the plaintiffs are required to “prove that the Federal Defendants either exercised coercive power or exercised such significant encouragement that the private parties’ choice must be deemed to be that of the government.” This standard is pivotal for the simple and elementary reason that the First Amendment doesn’t touch private conduct—only public conduct is curtailed by the Constitution. In order to attach to private conduct, the plaintiffs must satisfy the standards of what’s known as the “state action doctrine” which (as I have explained elsewhere) requires that the government exercise so much coercive control over a private actor “that the choice must in law be deemed to be that of the State.”

The Supreme Court has held that a state’s subsidization of the operating and capital cost of nursing homes, including paying the medical expenses of 90 percent of their patients—was not enough to satisfy the test. The reason for this stringent hurdle is important: a looser standard would convert a whole range of private conduct into government conduct, with all the baggage that entails, including liability for complying with the Constitution itself. Doughty’s tortured reading of the state action doctrine calls into question the entire lobbying industry that fuels Washington, D.C. For example, there’s lots of lobbying over Section 230 occurring on Capitol Hill on both sides of the aisle; Doughty’s opinion suggests it could all be unconstitutional.

Not to mention as a matter of sheer logic: Does anyone really believe that Elon Musk or Jeff Bezos or Mark Zuckerberg are under the utterly coercive control of Joe Biden? Absurd.

5. The injunction binds untold numbers of regular federal employees from speaking—while ignoring that they have First Amendment rights too.

Doughty ignores this entirely. As far back to 1967, the Supreme Court has held that public employees do not lose their free speech rights simply because they work for the government. If their speech touches on a matter of public concern, meaning it relates “to any matter of political, social or other concern to the community,” their rights to speak can outweigh the government’s contrary interests—here, presumably, in spreading disinformation on issues bearing on the COVID-19 vaccine. The argument that spewing misinformation is a valid government interest, again, is extreme on its face. Yet Doughty claims that the inclusion of differing facts online is part of the states’ “benefits intended to arise from participation in the federal system.”

Perhaps the saddest part of this story is the fact that now, in 2023, it’s not only the cynical, ideological zealots and their complicit lawyers who are willing to abuse the courts for political gain. Certain judges are in on it, too. Which makes it all the more critical that American citizens and lawmakers educate themselves on freedom of speech and the basics of American law.