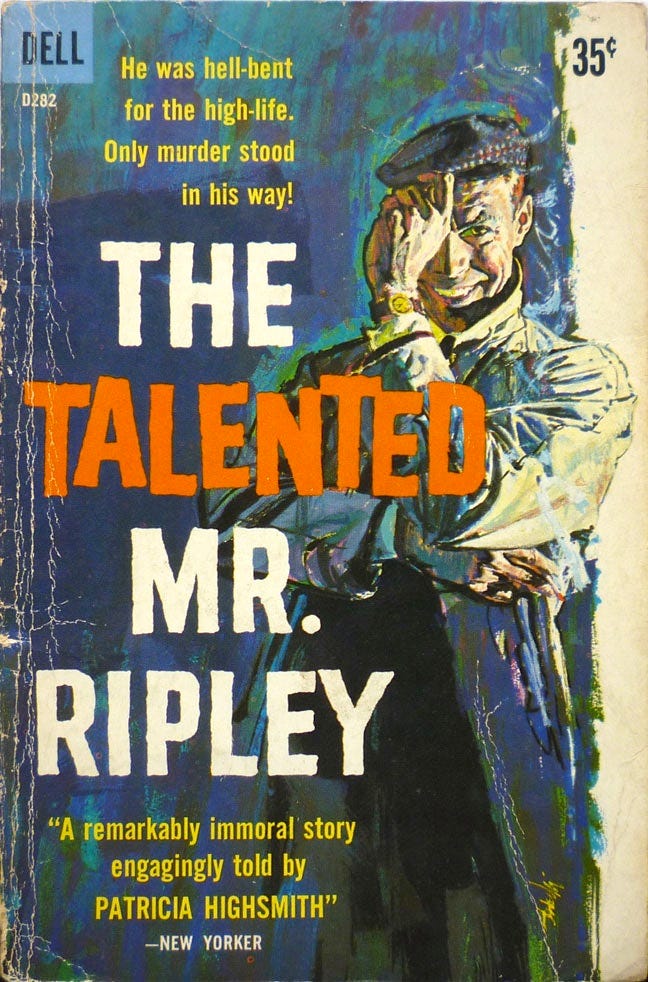

ANTHONY MINGHELLA’S THE TALENTED MR. RIPLEY did rather well at the box office upon release in 1999, and it was met very favorably by critics. I loved it myself at the time. But I hadn’t yet read the 1955 novel on which it was based, nor any of its sequels, which were written by American expat (born in Texas, died in Switzerland) Patricia Highsmith, a woman with a very dark imagination. Highsmith was a very prolific writer, and almost all of her fiction belonged to that vaguely named genre of “thriller.” Serious fans of her work would eventually dub the five-book Ripley series “the Ripliad,” and Minghella’s film seemed to reawaken, at least in America, interest in Highsmith and her work. This led to a new wave of Highsmith adaptations (prior to 1999 there were many films made from Highsmith’s novels, most of them European, a notable exception being Hitchcock’s Strangers on a Train), including Todd Haynes’s much-celebrated version of Highsmith’s groundbreaking lesbian novel Carol (aka The Price of Salt). And, as of April 4, we’ve come full circle with Netflix’s new adaptation of The Talented Mr. Ripley, called Ripley, by writer-director Steve Zaillian.

However, there is a problem: Minghella’s film, while it may be good in its own right (though I’ve cooled on it considerably over the years), is not a very good Ripley adaptation. As Highsmith’s The Talented Mr. Ripley opens, Tom Ripley has never killed anyone. By the end, he will have killed two: Dickie Greenleaf, whom Ripley has been sent to Italy, by Dickie’s father, to keep an eye on (the reasons why are a bit complicated), and whom Tom becomes somewhat obsessed with (an obsession that is not reciprocated); and Freddie Miles, Dickie’s friend, who becomes suspicious of Tom when Dickie disappears.

Underneath all of this is a subtle homoerotic subtext; this subtext is made text by Minghella, which he had every right to do, but doing so comes perilously close to excusing Ripley. By the end of the novel, we have a clear picture of Tom as a man who has discovered his ability to maintain a largely untroubled soul, even in the wake of having committed murder. A dangerous sociopath, in other words. Where Minghella found empathy for Tom, Highsmith sensed something else in her characters, and the world they inhabited. As the novels go on—at times, reading the five books of the Ripliad can feel like reading one long novel—the reader learns that the one murder Ripley committed that he regrets is that of Dickie Greenleaf. But he doesn’t regret it that much: Though he wishes Dickie were still alive, Ripley feels no real empathy for him. Ripley is also paranoid, afraid of water, delusional, even squeamish—though squeamish of spilled blood, not of what the blood was spilled from. On the delusional front, in Ripley Under Water, the last novel in the Ripliad, Tom reflects on his admiration for Oscar Wilde:

Something about Oscar’s life . . . was like a purge, man’s fate encapsulated; a man of goodwill, of talent, whose gifts to human pleasure remained considerable had been attacked and brought low by the . . . hoi polloi, who had taken sadistic pleasure in watching Oscar brought low. His story reminded Tom of that of Christ.

Given that Ripley Under Water is about Ripley being hounded by a sadist who wishes to bring him low, Ripley is taking a somewhat roundabout way of comparing himself to Jesus.

IN THE SECOND NOVEL, Ripley Under Ground, Ripley commits a third murder, this time to protect a complicated art forgery scheme from which he and recurring characters, the English gallery owners Jeff Constant and Ed Banbury, have been profiting for years. Ripley kills an American named Thomas Murchison, who has clued in to the fact (a theory, to Murchison) that someone has been producing paintings and claiming they were made by the celebrated (and dead, from suicide) artist named Derwatt. This is correct, and the forger, Bernard Tufts, a depressed and humiliated man, will eventually, and miserably, assist Ripley in disposing of the man’s body. As far as anyone else is concerned, Murchison has disappeared. When Ripley meets the man’s widow to answer her questions, Highsmith writes: “Tom felt sorry for her. He felt sorry that he had killed her husband.” That’s as much as he can manage. But for him, that’s a lot. In Ripley’s world, our world, the suffering of lobsters in a pot hurt his soul more. He could never kill a lobster.

The murders of Greenleaf and Murchison, as well as his part in the art forgery scheme, will, throughout the subsequent three novels, come back to haunt Ripley, in the form of suspicious police, or nosey sadists, or bereaved friends. Curiously, in a move that is frustratingly typical of Highsmith at her weakest (or oddest, anyway), when Dickie’s cousin travels to France to stay with Tom and his wife Heloise, absolutely nothing comes of it. Two books that deal with these past crimes almost not at all, other than as ancillary matters, are Ripley’s Game (a terrific novel in which Ripley ruins the remaining life of a dying man because Ripley feels the man insulted him at a party; the novel finds Ripley, and Highsmith, at their most cold-blooded) and the fourth novel, The Boy Who Followed Ripley. It’s in this later book that things really get interesting.

If Anthony Minghella wanted to foreground the question of Ripley’s sexuality, he should have just adapted The Boy Who Followed Ripley, both the worst and most interesting Ripley novel. A teenage American named Frank finds Ripley in the French village where he lives. Frank, the son of a recently deceased multi-millionaire, knows Tom’s history (though never charged, rumors of what Ripley may or may not have done hover over his life a raincloud). It transpires that Frank murdered his father. This seems to endear the boy to Ripley, but it’s not just that. One gets the sense that Frank loves Tom, and Tom might feel the same. They never act on this implied infatuation, but they spend a great deal of time together, and when Frank is kidnapped in Germany (where the two had been traveling, as though they were a couple), Ripley takes it upon himself to save the boy. Sex is brought up more often in this book than in any of the others. We learn that Heloise has something of a weak sex drive, and that if had it been stronger, Ripley might have left her. Also, Frank tells Ripley that the one time he tried to have sex with the girlfriend he loves, he failed, and was laughed at. And in one remarkable scene, the two murderers are described as lounging around Tom’s house, listening to Lou Reed.

There are many references to music in the Ripliad, almost all of it classical, the only kind Ripley likes. But Heloise, and Frank, like pop, and rock, and here they are listening to Lou Reed of all people. Reed’s own sexuality was more than a little fluid, and while Highsmith doesn’t say which of his albums is on the turntable, we find out later that it’s Transformer. Specifically the first two songs on side two: “Make Up” and “Satellite of Love.” It may be a reach, but still worth noting, that Transformer also features, on its first side, “Perfect Day,” one of Reed’s sweeter compositions, describing the kind of day that Frank and Tom seem to have enjoyed plenty of together, before the kidnapping, and “Walk on the Wild Side,” a song all about transsexuality and illicit encounters between people who exist in a world of desire outside of the standard, straight male/female pairing.

If you’re wondering why I bring up transsexuality, that’s because in the second of Ripley’s two attempts to deliver ransom money (supplied by Frank’s mother) to the kidnappers, the spot chosen (by Ripley) is a gay/drag bar. To better lose himself among the patrons and track the kidnappers when they arrive, Ripley dresses in drag, complete with cosmetics (“Make Up”) and, truth be told, in the time before those kidnappers arrive, he seems to be having an absolutely grand time. Highsmith writes about how free Ripley feels in these moments, and how he notices other men in the bar noticing him. Highsmith was a lesbian, and in 1980, when The Boy Who Followed Ripley was released, perhaps she, too, was feeling somewhat stronger and prouder in her own sexuality. In any case, as stupid and dangerous as Ripley behaves in both his attempts to hand off the ransom, it seems almost ancillary as to what Highsmith, or even Ripley, cares about.

The Boy Who Followed Ripley is not, finally, an uplifting novel for anyone who might see themselves in it. In the end, it’s rather desolate. It’s not just murder that casts a shadow over Ripley and the Ripliad, but suicide, as well. Even when suicide doesn’t occur in one of the novels, it’s still usually there, if only because Ripley leads the authorities to believe that was the fate of one of his murder victims. And there are still a number of suicides in the books. Chillingly, for all Ripley seemed to care for young Frank, when that books ends, and Ripley Under Water begins, he’s forgotten. Characters who meant far less, or seemed to, to Ripley than Frank come back again and again, but not Frank. The sadness Ripley feels at the end of Frank’s story, if that’s what he really feels, is fleeting, and he moves on from it as if Frank were a beloved painting that someone stole from him. The selfishness, the sociopathy, once more takes over. Since he can’t be blamed for Frank’s fate, he stops caring.

Highsmith’s Tom Ripley is many things: a snob, a killer, a traveler (the novels go everywhere from America to Germany to France to Morocco), and a poetic soul when it comes to art. But he is lacking something when it comes to humanity. He is not a misunderstood victim of circumstance. One woman calls him “the most evil man I have ever met.” That is the heart of Ripley.