Rogue Judge Cannon Hands Trump a Huge Gift, Tosses Classified Docs Case

What’s next for Special Counsel Jack Smith?

JUDGE AILEEN CANNON’S shocking decision to dismiss the indictment against Donald Trump for having taken classified documents from the White House and then obstructing the FBI’s efforts to retrieve them is more about politics than law. Before today, the only question in the case was whether her string of pro-Trump rulings and inexplicable delays reflected mere incompetence or something more like malice. That question is now settled beyond any doubt.

Cannon’s latest maneuver follows a gratuitous blueprint that Justice Clarence Thomas laid out for her in his opinion concurring in Trump v. United States—the case that gave Trump criminal immunity for official actions relating to the horrors of January 6th. Thomas suggested that Special Counsel Jack Smith’s prosecutions of Trump were invalid because the position of special counsel is unconstitutional.

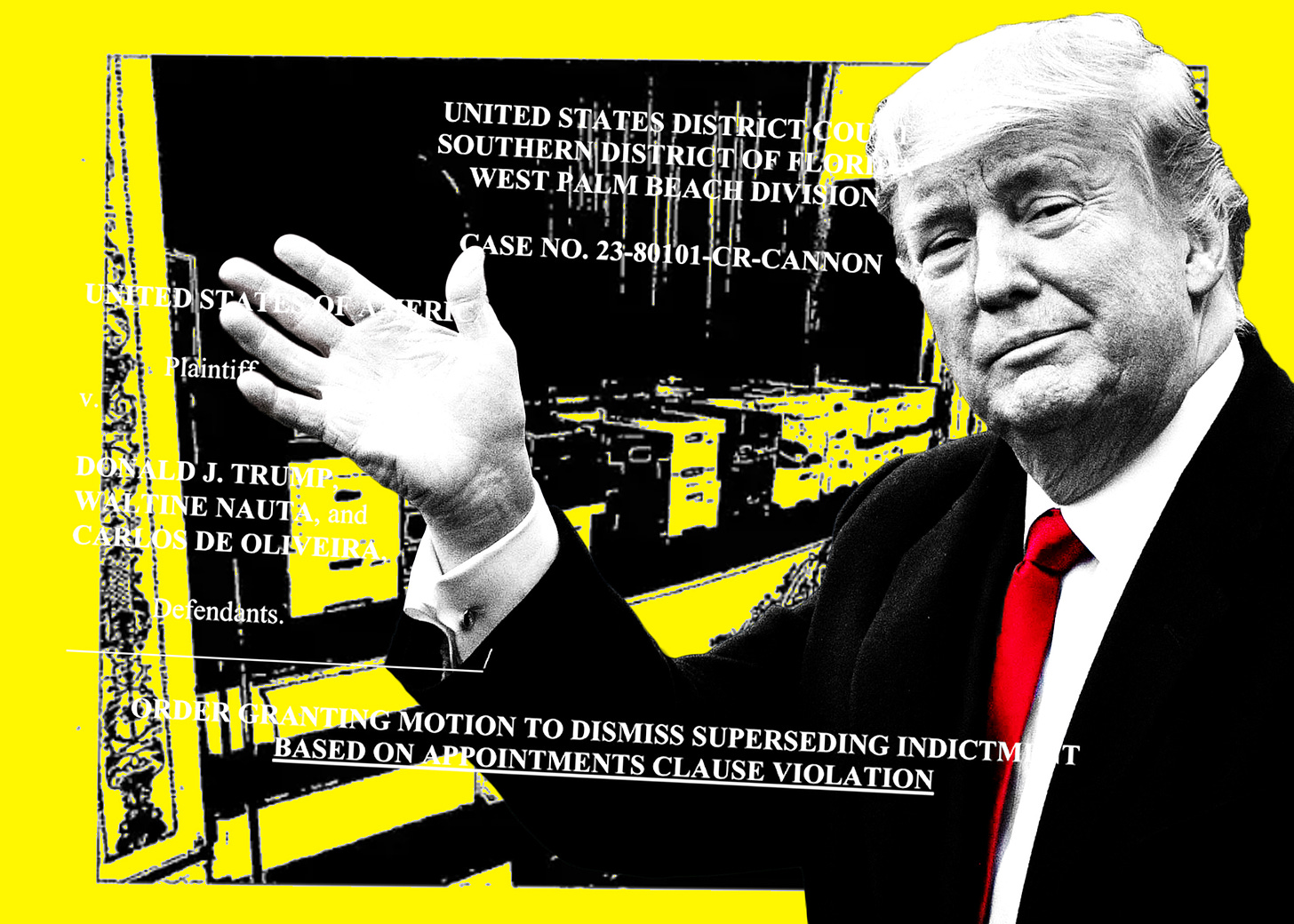

Cannon used exactly that radical rationale to toss out the Mar-a-Lago documents case.

Before discussing what comes next, let’s lay out the nuts and bolts of Cannon’s reasoning. Following Thomas’s advice, Cannon fastens her ruling on the Appointments Clause of Article II of the Constitution. Article II essentially creates three categories of federal employees. The first consists of principal officers—people in the government who answer directly to the president, like department heads in the cabinet, including the attorney general. Those folks have to be appointed by the president and confirmed by the Senate.

In the second category are inferior officers. The Constitution states that Congress can give department heads—like the attorney general—the authority to appoint inferior officers.

The third category is everyone else in the federal government—that is, regular employees.

Now for a bit of history: Like Jack Smith’s investigations of Trump, the Department of Justice’s 1973 investigation of President Richard Nixon and the Watergate scandal was led by a special counsel (or special prosecutor, as the position was then called). Nixon ordered that he be fired, resulting in the “Saturday Night Massacre.” To prevent such a crisis from recurring, Congress in 1978 passed the Ethics in Government Act, which created the “independent counsel”—a similar sort of prosecutorial office, but appointed by a three-judge panel and not fireable at will by the president, unlike traditional U.S. attorneys and DOJ prosecutors. The constitutionality of that law was upheld in 1988 by the Supreme Court, which ruled in Morrison v. Olson that the independent counsel did not violate the Appointments Clause. Because the independent counsel was an inferior officer and not a principal officer, the job did not require Senate confirmation and Congress could vest the power of appointment in a three-judge panel.1

The independent counsel statute lapsed in 1999, and in its place, DOJ promulgated regulations establishing a mechanism for appointment of a special counsel. Under those regulations, Smith can only be fired for “good cause.” It is under those regulations that Robert Mueller investigated Donald Trump and Russia’s interference in the 2016 election, that John Durham then investigated the Mueller investigation, that Robert Hur investigated Joe Biden’s mishandling of classified documents, that David Weiss obtained Hunter Biden’s recent conviction, and that Jack Smith has run his two investigations of Trump.

Those regulations have never been tested in a higher court, but were presumed to be constitutional in light of Morrison. When Trump crony Paul Manafort attempted a desperate defense by challenging the appointment of Special Counsel Robert Mueller, his lawyers didn’t argue that Mueller was unconstitutionally appointed, complaining instead that the indictment against him exceeded the authority conferred by then-Acting Attorney General Rod Rosenstein’s order appointing Mueller. (The district judge roundly rejected Manafort’s argument.)

Now, in her sweeping dismissal order, Judge Cannon has held that the general statutes allowing Attorney General Merrick Garland and his predecessors to hire prosecutors, including one (28 U.S.C. § 515(b)) that broadly references attorneys “specially retained under authority of the Department of Justice,” were not good enough for hiring Jack Smith, an inferior officer.

Cannon additionally found that Jack Smith’s paycheck violates the Appropriations Clause of Article I, which prohibits money being “drawn from the Treasury” unless authorized by an act of Congress.2 According to Cannon, Smith is relying on the Department of Justice Appropriations Act of 1988 to pay the bills. Ever since the independent counsel law lapsed in 1999, she claims (rather summarily), there has been no funding mechanism for a prosecutor conducting this sort of probe; there is no “other law,” in other words, that appropriates money for Smith’s investigation. For Cannon, it’s not enough for Congress to fund DOJ, of which Smith is a part; Congress needs to be very specific in its intention to allow for a prosecutor like Smith—or any of the other special counsels—who operates with structural independence from the president.

IF IT WEREN’T FOR CLARENCE THOMAS’S SIGNAL, it’s unlikely Cannon would have used these constitutional arguments to dismiss the classified documents case against Trump. (While Trump’s lawyers had raised the constitutionality of Smith’s appointment as part of their strategy to try every imaginable argument no matter how absurd, Cannon didn’t previously seem interested.)

Legally, her opinion is extremely weak. But that’s really beside the point. If Trump wins the election, he’ll call off the prosecution anyway by directing his DOJ to amend the special counsel regulations to give himself the authority to fire Smith—or by just ignoring them altogether. Or Trump’s attorney general might shut down the investigation based on the Clinton-era memo supposedly barring the criminal prosecution of a sitting president.

The Department of Justice could act now, or after the election if Trump is defeated, to appeal the ruling to the Eleventh Circuit and then to the Supreme Court, where it might lose. Or DOJ could refile the indictment in the District of Columbia using a regular team of prosecutors rather than Smith. The election will decide many things, including the fate of this case.

And don’t be surprised if the lawyers defending Trump in Smith’s prosecution related to January 6th file a new motion to throw out that case drawing on Judge Cannon’s logic.

One last big thought to bear in mind: The entire point of the position of special counsel—and its historical predecessors, the special prosecutor and the independent counsel—is to protect high-level individuals from political persecution by insulating prosecutors from the president’s hiring and firing whims. Without some measure of prosecutorial independence, presidents could prosecute political enemies while evading accountability for their own criminal behavior. The Supreme Court just made clear in Trump v. United States that political prosecutions are perfectly okay under the Constitution—indeed, protected by it. Meanwhile, Team Trump has laid out plans to do just that. So Judge Cannon’s ruling today not only harms the pursuit of justice by killing a prosecution for taking troves of classified information from the White House and keeping it from its legal owners, the American people. It also gives a boost to the presidential frontrunner hellbent on retribution in the next administration.

Full disclosure: I worked for an independent counsel, Ken Starr, during the Whitewater investigation of President Bill Clinton. Another lawyer on that investigation, Brett Kavanaugh, now a Supreme Court justice, wrote a law review article in 1998 about the constitutional questions surrounding special counsels that could prove especially interesting if the question of the constitutionality of Jack Smith’s office were to go to the Supreme Court.

Epic irony alert: Recall that it’s the Appropriations Clause that gave rise to Trump’s first impeachment over his withholding of funding appropriated for Ukraine to stave off Russian aggression absent a promise by Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky to announce an investigation into Joe Biden.