Romney Alone. Again.

On June 1, 1950, freshman Senator Margaret Chase Smith, Republican from Maine, took to the Senate floor to deliver what became known as her “Declaration of Conscience.”

Months earlier, her colleague Joseph McCarthy had launched his conspiracy theories on the world, accusing unknown plotters in the deep state of trying to subvert the country. While many Republicans were appalled by McCarthy’s baseless charges and his refusal to provide documentary evidence, most of them kept their heads down.

Smith chose to speak out, giving one of the most memorable speeches in the history of the United States Senate.

The Senate’s official history recalls the moment:

"Mr. President," she began, "I would like to speak briefly and simply about a serious national condition. . . . The United States Senate has long enjoyed worldwide respect as the greatest deliberative body. . . . But recently that deliberative character has . . . been debased to . . . a forum of hate and character assassination."

She spoke for just 15 minutes, as McCarthy himself sat listening in the chamber. “The Democratic administration has greatly lost the confidence of the American people,” Smith said.

Yet to displace it with a Republican regime embracing a philosophy that lacks political integrity or intellectual honesty would prove equally disastrous to this nation. The nation sorely needs a Republican victory. But I don't want to see the Republican party ride to political victory on the Four Horsemen of Calumny—Fear, Ignorance, Bigotry and Smear.

I doubt if the Republican party could—simply because I don't believe the American people will uphold any political party that puts political exploitation above national interest. McCarthy tried to laugh off the attack with a proto-Trumpian insult (perhaps written by Trump’s own mentor Roy Cohn), deriding Smith and her supporters as “Snow White and the Six Dwarfs.”

Four and a half years later, in December of 1954, the Senate censured McCarthy for conduct “contrary to senatorial traditions.” As the Senate history recounts: “McCarthy’s career was over. Margaret Chase Smith’s career was just beginning.”

So far, the congressional GOP seems to regard Donald Trump’s conduct as a matter of news cycles rather than an historic moment.

The Sunday performances by Senator Ron Johnson and Congressman Jim Jordan were just the latest indices of the eagerness of elected Republicans to ingratiate themselves with the president, even at the expense of their own humiliation. In their calculation of risk-reward, they have decided that the rewards which come from short term embarrassment are better than taking a painful stand for posterity.

Johnson clearly was not thinking about how the official Senate history will remember his Sunday performance on Meet the Press, where he floated conspiracy theories, proclaimed his distrust of America’s intelligence agencies, and otherwise demonstrated his total fealty to Donald Trump.

And to be honest, in the short term, this strategy has a certain rough logic: If Republicans break with Trump now, they will be filleted by the Trumpist media and risk being excommunicated by the Vichy GOP for premature anti-Trumpism. Not unreasonably, they fear that they would be black-balled from any future participation in an attempt to rebuild a post-Trump Republican party. If they spoke out now, they would be become, according to the fashionable rationale of the moment, irrelevant.

And elected Republicans seem to fear irrelevance even more than they do the destruction of constitutional norms, the eradication or the rule of law, or the interference of foreign governments in U.S. elections. As the Washington Post reported this weekend:

Across the country, most GOP lawmakers have responded to questions about Trump’s conduct with varying degrees of silence, shrugged shoulders or pained defenses. For now, their collective strategy is simply to survive and not make any sudden moves.

Behind the scenes there is reportedly growing anxiety. Maybe, someday, some senators like Lamar Alexander or Richard Burr might say something about it.

In the meantime, Nebraska’s Ben Sasse is still trying to decide who he wants to be when he grows up (or at least what he’s willing to say until after the Senate primary); and Susan Collins is once again furrowing her frequently-worried brow.

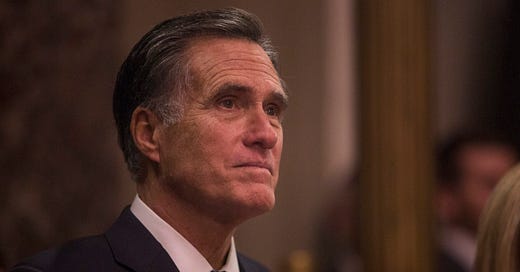

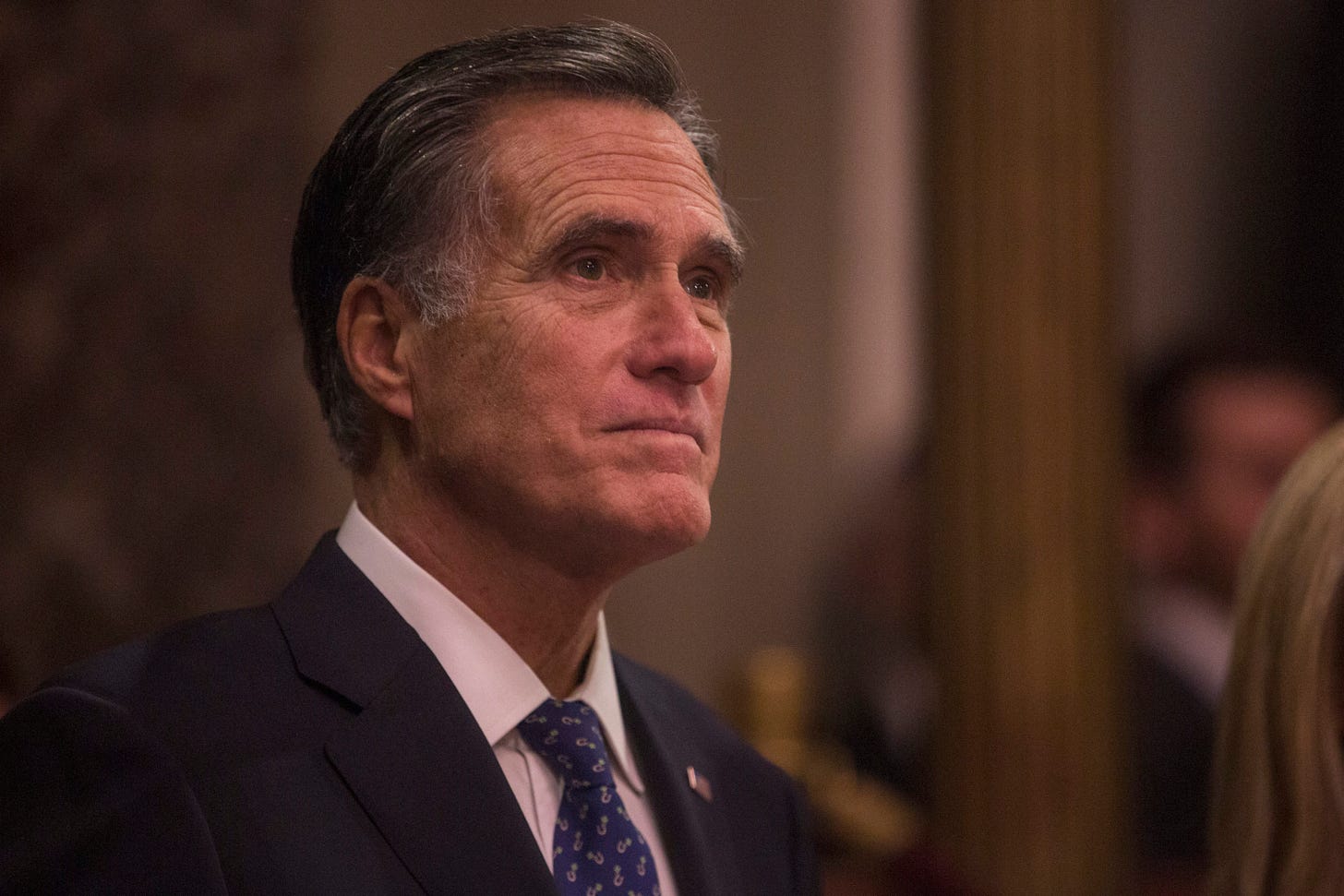

Which leaves Mitt Romney.

“If the president asked or pressured Ukraine’s president to investigate his political rival, either directly or through his personal attorney,” the Utah senator said, “it would be troubling in the extreme."

And when Trump doubled down, calling on China to join in probing the Bidens, Romney followed went further. “By all appearances,” he tweeted, “the president’s brazen and unprecedented appeal to China and to Ukraine to investigate Joe Biden is wrong and appalling.”

Romney did not take the easy-out argument that Trump was either just “joking,” or that the president’s real concern is simply rooting out corruption. “When the only American citizen President Trump singles out for China’s investigation is his political opponent in the midst of the Democratic nomination process,” Romney said, “it strains credulity to suggest that it is anything other than politically motivated.”

(To be fair, Sasse also pushed back, telling a local newspaper: “Americans don’t look to Chinese commies for the truth. If the Biden kid broke laws by selling his name to Beijing, that’s a matter for American courts, not communist tyrants running torture camps.”)

Trump noticed. The American president may not understand the nuances—or even basics—of trade policy, nuclear proliferation, or the Constitution. But by God, he keeps up with his mentions on Twitter. Trump unleashed a series of snarky tweets at the GOP’s 2012 nominee.

https://twitter.com/realDonaldTrump/status/1180484483147059200?s=20

https://twitter.com/realDonaldTrump/status/1180487139546546182?s=20

After a few hours, he circled back for more:

Trump evidently lacks advisers who would tell him that senators cannot be impeached. Not that it would matter if they did.

This is not, of course, the first time Romney has clashed with Trump. During the 2016 campaign, he was one of Trump’s harshest critics, calling him a “con man and a fake.” Before he was sworn in as a senator earlier this year, Romney wrote an op-ed in the Washington Post suggesting that he would be a thorn in the president’s side.

Romney said that he would support Trump’s policies when he agreed with them. “But,” he wrote, “I will speak out against significant statements or actions that are divisive, racist, sexist, anti-immigrant, dishonest, or destructive to democratic institutions.”

That seemed to presage great things, only to be followed by varying degrees of disappointment. Until now.

Actually, Romney has not gotten the credit he deserves. While he has not devoted himself to 24/7 criticism of Trumpism, (and is still haunted by that picture of the frog legs dinner), the reality is that Romney has stepped up at the decisive moments.

Almost alone among his colleagues, Romney seems focused on the verdict of history.

In April, after the release of the Mueller report, Romney was one of the few Republicans who noted the gravity of the charges. At the time, I naively thought that his statement would jar, or at least jostle the consciences of his fellow Republicans. “In fact,” I wrote then, “all it did was to highlight (once again) how badly late-stage Trumpism has shrunken those consciences. What we got instead was the usual combination of foot-shuffling, denial, and silence.”

Romney got some scattered expressions of support from folks on the left, but that tended to be overwhelmed by critics who wanted to know what he intended to dooooo about it? And there was the usual chorus of denunciations from progressives who insist that no criticism of Trump deserves praise unless it is accompanied by a complete rejection of conservatism itself. This, however, is not strategy; it is petulance. Serious progressives who regard Trump as a national emergency should welcome allies, not sneer at them. And unless they learn that lesson, they will get President Trump for another four years.

Romney’s break with Trump is not without risk to the first term senator. But then again, neither is Trump’s attack on a member of the Senate jury. Leaving aside Trump’s own apparent obsession with Romney (who got a higher percentage of the popular vote than Trump himself), his attacks are also an unsubtle warning to other senators who might be tempted to speak out.

But this sort of intimidation only works as long as the wall of silence holds.

What would happen if three or four—or eight or nine—Republicans senators joined Romney? How would Trump react to a critical mass of senators who pushed back?

What would happen if a half dozen senators who remembered the legacy of Margaret Chase Smith joined together to condemn “Fear, Ignorance, Bigotry and Smear”? Would Trump tweet insults at them all? And how would their Senate colleagues react then?

As the impeachment inquiry progresses and we find more evidence of exactly what Trump did with regard to foreign interference in U.S. elections, we may well find out.

Until then, Romney stands alone. Again.