The Roots of the Right’s Love of Dictators

A review of ‘America Last’ by Jacob Heilbrunn.

America Last

The Right’s Century-Long Romance with Foreign Dictators

by Jacob Heilbrunn

Liveright, 249 pp., $28.99

IT’S HARDLY NEWS THAT the intellectual alliances of the Cold War are falling apart. At the end of World War II, a coalition of conservatives, anti-totalitarian liberals, and centrists put aside their philosophical and political differences to limit the growth of Soviet and Chinese Communist power. Nowhere was this coalition stronger—and the divisions within it therefore more inconspicuous—than in the United States, the one nation strong and wealthy enough to provide the economic, political, and military power to hold the Western alliance together and keep it safe from Soviet aggression.

The anti-Communist coalition was never all-encompassing, though, and people beyond its ideological borders didn’t share its goals. Since the birth of the Soviet Union in 1917, some on the American left greeted Communist proclamations and the rapid rise of a worldwide totalitarian movement as signs of mankind’s progress towards freedom. Less well known is the story of the many right-wingers in the anti-Communist alliance who had their own repressed authoritarian cravings.

In his 2008 book They Knew They Were Right, Jacob Heilbrunn, longtime editor of the National Interest, explored and criticized the differences between neoconservatives and other liberals. The Center for the National Interest, the organization that publishes the National Interest, advocates a “realist” approach to foreign affairs, in contrast to liberal hawks and neoconservatives, both of whom favor (according to the group’s website) the “promiscuous use of American power abroad.” At the end of the George W. Bush administration, just past the nadir of the Iraq War, this seemed to be the primary fact of American foreign policy thought.

Sixteen years later, with one unfortunate and irrelevant exception, Heilbrunn largely departs from criticizing neoconservatism in his new book. America Last addresses the growing danger of authoritarianism—in the United States from the Trumpist Republican party, and abroad from the likes of Hungary’s Viktor Orbán and his allies among Europe’s populist parties. Heilbrunn searches for the historical roots of the right wing’s interest in authoritarianism, trying to explain why so many conservatives in academia, politics, and journalism, who were once united with liberal centrists in waging the Cold War, suddenly abandoned any belief in the democratic idea. Now they seem oblivious to the growing threats to what were once assumed to be our country’s basic ideas and system of governance.

At the Cold War’s end, Francis Fukuyama declared that “The triumph of the West, of the Western idea, is evident first of all in the total exhaustion of viable systematic alternatives to Western liberalism” (emphasis in original). In recent years, however, many on the right have left their former allies in the lurch, and instead sought to create a new society that would dispense with what they saw as the unappealing cultural liberalism of multiculturalism, feminism, abortion, gay rights, transgender rights, and the sidelining of religion in public life.

To the illiberal right—the new old right—social order needs stability and firm rule, not the kind of democracy in which one’s assertion of political liberty could lead, as they see it, to internal collapse and moral rot. To these figures, authoritarian regimes, now dubbed “illiberal democracies” (an oxymoron if ever there was one), are preferable to the kind of democracy they see as destroying the United States. What they desire, Heilbrunn asserts, is “revolution to preserve tradition, to capture the future by returning to a mythical past.” They oppose cancel culture when practiced by the left, but use it themselves to censor any ideas they revile. And, it turns out, in the name of illiberalism, many are happy to sacrifice democracy.

In the last century, some on the left supported and glamorized first Stalin and Mao, and then Fidel Castro and Hugo Chávez. Some of the right did the same first with Franco and Pinochet, now with Orbán and Putin. As Heilbrunn puts it, the “illiberal imagination . . . has persisted for over a century on the Right.”

HEILBRUNN ARGUES THAT the right’s love of authoritarianism started in the Progressive era, when the early conservative George Sylvester Viereck, along with H.L. Mencken, began to venerate Kaiser Wilhelm II. Both made pilgrimages to Berlin and in defense of German aggression made arguments that will sound familiar today: “Mencken and Viereck engaged in whataboutism, scorned Western liberalism as a bankrupt ideology, and elevated authoritarianism above democracy . . . converting Kaiser Wilhelm into a crusader for freedom and Wilson into a barbaric warmonger.” When Germany was defeated, both men, joined by the historian Harry Elmer Barnes and others, developed a revisionist history that sought to blame the war not on the kaiser and German policy, but on American elites, bankers, and arms manufacturers.

After the First World War, a new hero emerged for the right: Italy’s Benito Mussolini, a socialist-cum-militarist. His new ideology of a “corporate state” would replace corrupt democracy with a strong nation-state that could “be defended against the globalists.” Heilbrunn adds that a “highbrow” group of “intellectuals and politicians” admired Mussolini’s “readiness to crack down on Communists.”

Heilbrunn, however, is wrong in claiming that “the greatest and most lasting fervor for Mussolini emanated from the American Right, which lauded him for dispensing with democracy to defend traditional religion and family values.” Major figures prominent in the American liberal and labor movements and left-wing communities admired Mussolini as well.

Prominent among this group was the founder of the modern American labor movement, Samuel Gompers, president of the American Federation of Labor. For example, in the American Federationist, the AFL publication he edited, Gompers wrote an unsigned book review in 1923 extolling Mussolini’s concept of a corporate state. Gompers quotes the book’s author as saying that Mussolini was building “a functional democracy.” Then, in his own words, Gompers describes Mussolini as “a man whose dominating purpose is to get something done; to do rather than theorize; to build a working, producing civilization instead of a disorganized, theorizing aggregation of conflicting groups.” Mussolini was creating “a nation of collaborating units of usefulness.” The “industrial democracy” Mussolini was building in Italy was based on “declarations and phrases which might easily enough have been taken from the mouths of American trade unionists.”

Gompers did not approve of Mussolini’s use of violent tactics to gain power. But, as he told his members in a signed editorial the next year, “allowance must be made” for Mussolini’s actions. They were “due partly to Communist intrigue” which led to an electoral “mandate” from the Italian people that he take power. It was the action of left-wing radicals that forced Mussolini to act to save Italy.

As the late Paul Hollander noted in From Benito Mussolini to Hugo Chavez, Lincoln Steffens, famous for saying after visiting Soviet Russia that “I have seen the future and it works,” thought the same about fascist Italy, as did the British socialist Harold Laski. Mussolini’s corporate state was the template for liberals’ belief in national planning, which is why New Republic founder Herbert Croly admired him. Various figures involved in the National Recovery Administration, the prominent and controversial New Deal agency, held Mussolini and his ideas in esteem, including FDR’s choice to head the agency, Brig. Gen. Hugh Johnson, who carried fascist literature around with him and, in his farewell address, praised the “shining name” of Mussolini. Yes, many early admirers of Mussolini on the left would change their minds about him even before the Second World War, but it would be wrong to understate the intensity and duration of their high regard for him.

HEILBRUNN IS MORE PERSUASIVE WHEN presenting the views of prominent American self-proclaimed fascists. He devotes special attention to the influential diplomat and writer Lawrence Dennis, who wrote two pro-fascist books and also wrote for a pro-Nazi newspaper; the propagandist, extremist anti-Communist, and antisemitic conspiracy theorist Elizabeth Dilling; and the president of the New York Economic Council Merwin K. Hart, whose attention was mainly focused on supporting Franco, and who after the war joined the John Birch Society and became a Holocaust denier.

Pro-fascist propaganda in the 1940s led to what Heilbrunn calls “round two” for George Viereck, who wrote after a 1933 trip to Germany that his old friend Kaiser Wilhelm felt that Adolf Hitler had “completed the work that Bismarck began,” and had “saved Germany and the world from Bolshevism.” Viereck was so infatuated with Hitler that he became a paid agent of and propagandist for the regime in the United States. During the war, he unashamedly became a lobbyist for the Third Reich.

Of all those Heilbrunn discusses, the smartest and most serious was Dennis, whom Heilbrunn groups with other figures who favored “an intelligent fascism.” Dennis, he writes, saw as allies FDR’s populist opponents Huey Long and Father Charles Coughlin, whom Dennis rightfully called “precursors of fascism,” although they themselves did not adopt that ideology. Dennis was, writes Heilbrunn, “the leading fascist intellectual in America,” seeking salvation for the United States by creation of its own “fascist elite.”

Dennis was unique because he was held in high regard by his liberal intellectual opponents, who considered him a serious analyst of American society. Even Arthur M. Schlesinger Jr. wrote that he brought to fascist advocacy “powers of intelligence and style which always threatened to bring him . . . into the main tent.” Marxist intellectuals like John Strachey thought Dennis successfully revealed “the fatal contradictions inherent in large-scale capitalism,” and even the anti-totalitarian and anti-Stalinist “council communists” Paul Mattick and Karl Korsch admired him. Korsch argued against those who worried that Dennis was a real, Nazi-type fascist, denying that his writing was “a handbook and pocket guide for the American Hitler to come.” Mattick believed Dennis was simply a run-of-the-mill “reactionary” who developed a sound critique of American-style state capitalism.

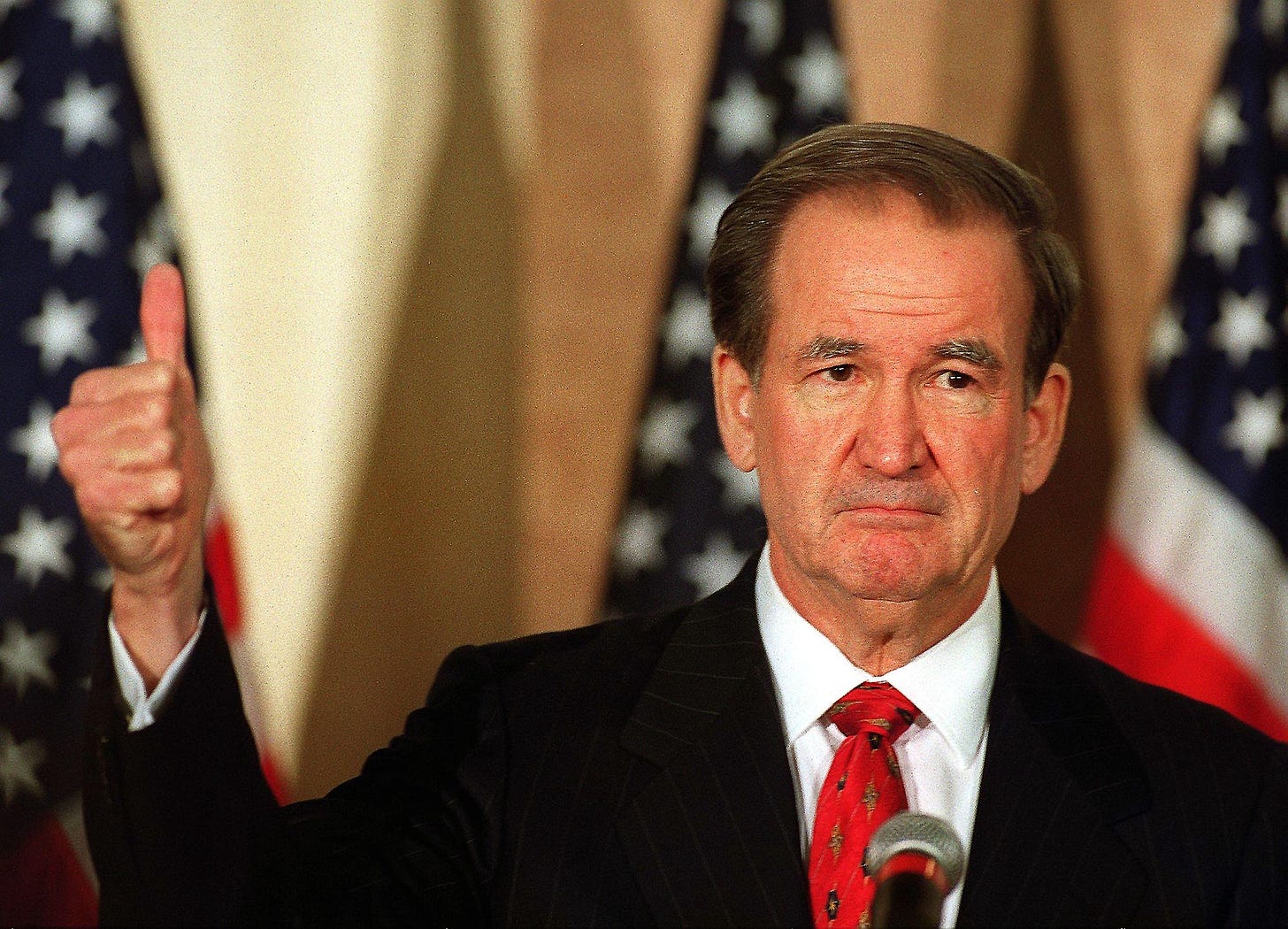

IN HIS LAST CHAPTERS, covering the later twentieth century to the present, Heilbrunn turns first to the Buckleyite right and the early years of National Review, with a brief sideline to the neoconservatives and Jeane Kirkpatrick, and finally to Donald Trump’s predecessors, especially Pat Buchanan, his American Conservative magazine, and the broader paleoconservative right.

Buckley is usually remembered as a serious and moderating influence on postwar conservatism. He has received much praise over the years for firing the notorious antisemite Joseph Sobran from his magazine and for, through force of argument and intellectual leadership, exiling the Birchers from American conservatism.

Yet Heilbrunn dissents from that assessment, arguing that “trolling the libs, denouncing political correctness, and overthrowing the deep state . . . all had their sources in Buckley’s early efforts.” Buckley’s associates were, in Heilbrunn’s judgment, proponents of “illiberalism and hostility to democracy.” Heilbrunn notes that Buckley defended Senator Joseph McCarthy’s populist anti-Communist crusade, supported alliances with reactionary regimes such as apartheid-era South Africa, and opposed moderate conservatives like Dwight Eisenhower. Buckley was strongly influenced by the aristocratic libertarian Albert Jay Nock, whose “contempt for the masses, disdain for government, and skepticism of democracy,” Heilbrunn argues, “would become the leitmotifs of Buckley’s career.” A second influence was Willmoore Kendall, who fused elite conservatism with populism, and whose opposition to democracy and love for McCarthy became Buckley’s as well.

In his new book’s brief treatment of neoconservatism, Heilbrunn misses the mark. He shoehorns Jeane Kirkpatrick’s famous essay “Dictatorships and Double Standards”—which led Ronald Reagan to appoint her U.S. ambassador to the United Nations—into the separate tradition of right-wing illiberals. Whatever critique one may have of Kirkpatrick’s essay—and many critiques were written when it was published—neither it nor she were right-wing or admiring of strongmen.

Heilbrunn argues that Reagan used the reasoning in Kirkpatrick’s essay to offer support to “right-wing regimes and rebel movements, while doubling down on confronting communist ones.” What he ignores is that in the polarized Cold War world, each bloc had its own proxies, and he does not discuss whether those the Reagan administration backed—like the contras in Nicaragua—may have been the only realistic alternative to the even more dangerous Soviet proxies. In the case of El Salvador, for example, Kirkpatrick supported the centrist government of José Napoleón Duarte, not the right-wing death squads. In Africa, the choices were even more complex. That the Reaganites backed the undemocratic warlord Jonas Savimbi in Angola is true; but Heilbrunn does not comment on whether the Soviet and Cuban proxy in that civil war, José Eduardo dos Santos, might have been even worse.

More to the point, if the neoconservatives were the predecessors of MAGA, Heilbrunn offers no explanation of why many neocon intellectual figures have taken the lead in forging a coalition of conservatives, centrists, and even progressives and left-liberals to oppose Trumpist populism.

HEILBRUNN IS ON STRONGER GROUND in his concluding section, focused on the pre-Trumpist populism of Pat Buchanan, whose quixotic campaign for the Republican presidential nomination in 1992 had all the themes and arguments made by Donald Trump and his followers in 2016. Buchanan took aim primarily at the neoconservatives, ironically in largely the same terms as does Heilbrunn—a contradiction he fails to address. Unlike Kirkpatrick and her supporters, Buchanan opposed NATO enlargement into Eastern Europe. He looked fondly upon the anti-gay, pro-Christian family agenda he believed existed in post-Soviet Russia. And he opposed Bill Clinton’s military action to defend Bosnian Muslims and Kosovars against the right-wing nationalist regime in Serbia. (In this, I might add, Buchanan was joined at rallies by the Stalinist writer Alexander Cockburn, making these events a Red-Brown alliance.)

What Buchanan favored, Heilbrunn argues with merit, was an “internationalism rooted in those small towns and conservative values and in whiteness, whether in the US or in Serbia or Russia or South Africa or elsewhere.” Indeed, he quotes favorably Robert Kagan’s observation that Republicans were adopting “a Neville Chamberlain attitude toward the population of Kosovo.” Heilbrunn calls that view “a staple of neocon discourse, but in the case of Buchanan it was quite accurate.” Heilbrunn does not mention—neither in his discussion of paleoconservatives nor his exploration of neoconservatives—what his rule is for judging the Chamberlain attitude sound or foolish.

Buchanan condemned the very neoconservatives Heilbrunn detests, accusing them much as Heilbrunn does of favoring intervention everywhere. Buchanan, however, added the accusation that their thoughts, words, and actions were on behalf of Israel and “its amen corner in the United States,” referring to American Jews. He objected to the so-called “crusading interventionism” favored by the neoconservatives and the attempts to promote democracy abroad—instead of the old anti-interventionism and isolationist doctrines of the pre-Cold War right. In Buchanan’s warped worldview, that meant sympathy for Hitler and even—as he wrote in his 2009 revisionist history, Churchill, Hitler and the Unnecessary War—the claim that the war was forced upon Hitler by Western interventionism.

Buchanan was the first political figure to show overt support for Vladimir Putin’s regime, which he viewed as a bastion of white, Christian, and traditional moral values. As Heilbrunn writes, in the 1990s, Buchanan “consistently voiced Moscow’s geopolitical line, warning that NATO expansion and intervention in the Balkans were colossal errors.” In this, too, he forged the path to Trump’s current positions. It is ironic, Heilbrunn reveals, that as he was vying with Buchanan for the presidential nomination of the Reform Party in 1999, Trump castigated Buchanan for implying that Hitler was only “a fringe element who would never come to power” (Buchanan’s words) and for “having a love affair with Adolf Hitler.”

As his history butts up against the present, Heilbrunn notes that various paleocons have joined Buchanan in paying homage to Orbán as their inspiration and hope for a new type conservative order, joined by Rod Dreher and, most significantly of all, Tucker Carlson.

THE FIGHT TO PRESERVE LIBERAL DEMOCRACY and the international liberal order created at the end of Second World War is now in danger from Putin’s Russia and Xi’s China, among others. “Conservatives” of the Trumpist variety seek an international illiberal order that would bring an end, in the words of a 2019 open letter that Heilbrunn quotes, to “tyrannical liberalism” and the “fetishizing” of “individual autonomy.”

Heilbrunn warns his readers that “For Trump and his MAGA acolytes, supporting Russia and disparaging Ukraine amounted to a continuation of war by other means on the Biden administration and deep state.” In other words, the MAGA right’s foreign policy reflects its domestic politics. An illiberal United States would be a natural ally of illiberal Russia, and illiberal Russia can help create an illiberal United States. The “vision of Buckley, [Senator Joe] McCarthy, and Kendall,” Heilbrunn warns, of subduing “liberal malcontents who had insinuated themselves into permanent positions in government” would come to an end, and the so-called “administrative state” and “deep state” would be vanquished.

In our fight against illiberal democracy, Jacob Heilbrunn has given us a history of what he concludes is the “long and melancholy saga of the American Right’s self-abasement before foreign tyrants.” Those who still think of themselves as conservatives should read this book and learn about what some of the leaders they admire have in store for our country.