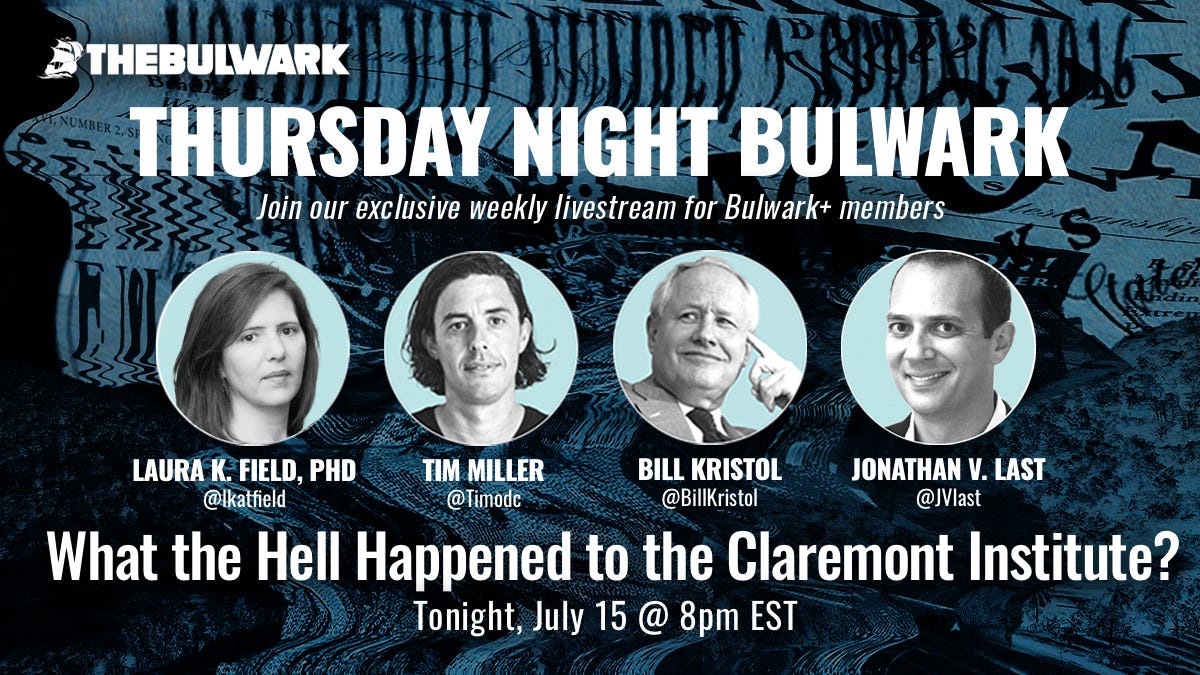

Tonight is TNB! Come hang out with me, Tim Miller, Bill Kristol, and our guest Laura Field to talk about the descent of the Claremont Institute, the East Coast / West Coast Straussian beef, and other tales from the Conservatism Wars.

Bring your A-game to the chat.

And remember: It’s only for members of Bulwark+.

1. “There Will Be No Trump Coup”

In the course of his four-year odyssey to create the Platonic ideal of anti-anti-anti-anti-Trumpism, Ross Douthat wrote some interesting things. Let’s take a brief tour through the final weeks of 2020.

On October 24, Douthat made a “just asking questions” case for Donald Trump.

“There are some ways that Trump has been better than I feared, and things he’s done that I wholeheartedly support. But he’s also the most corrupt American president of modern times: The liberals are wrong to see him as a dictator, but that doesn’t make his web of self-enrichment and pardons for cronies and Ukrainian abuses a good thing.”

On November 7, he asked “Is There a Trumpism After Trump?”:

“Trump will exit the presidency with a complicated and uncertain legacy—as both the man who opened the way to a possible populist majority, and (for the next four years, at least) one of the biggest potential obstacles for Republicans who want to tread that path.”

On January 5, he wrote that he was rooting for the Georgia Republican Senate candidates to lose because that outcome would help the party slough off the person of Trump:

“[S]omewhere between the wipeout of the Republican Party that I once expected and the 2024 Trump restoration that I fear, there’s a world where the party spends the next four years very gradually distancing and disentangling itself from its Mad Pretender and his claims.”

But the most interesting Douthat lines came from his October 10 column: “There Will Be No Trump Coup.”

“Three weeks from now, we will reach an end to speculation about what Donald Trump will do if he faces political defeat, whether he will leave power like a normal president or attempt some wild resistance. Reality will intrude, substantially if not definitively, into the argument over whether the president is a corrupt incompetent who postures as a strongman on Twitter or a threat to the Republic to whom words like “authoritarian” and even “autocrat” can be reasonably applied. I’ve been on the first side of that argument since early in his presidency, and since we’re nearing either an ending or some poll-defying reset, let me make the case just one more time.”

“There is still no Trumpian equivalent of Bush’s antiterror and enhanced-interrogation innovations or Obama’s immigration gambit and unconstitutional Libyan war. Trump’s worst human-rights violation, the separation of migrants from their children, was withdrawn under public outcry. His biggest defiance of Congress involved some money for a still-unfinished border wall. And when the coronavirus handed him a once-in-a-century excuse to seize new powers, he retreated to a cranky libertarianism instead. All this context means that one can oppose Trump, even hate him, and still feel very confident that he will leave office if he is defeated, and that any attempt to cling to power illegitimately will be a theater of the absurd.”

“Meanwhile, the scenarios that have been spun out in reputable publications — where Trump induces Republican state legislatures to overrule the clear outcome in their states or militia violence intimidates the Supreme Court into vacating a Biden victory — bear no relationship to the Trump presidency we’ve actually experienced.”

Douthat concluded this essay by saying that the real danger was . . . liberalism:

With American liberalism poised to retake presidential power, it needs clarity about its own position. Liberalism lost in 2016 out of a mix of accident and hubris, and many liberals have spent the last four years persuading themselves that their position might soon be as beleaguered as the opposition under Putin, or German liberals late in Weimar.

But in reality liberalism under Trump has become a more dominant force in our society, with a zealous progressive vanguard and a monopoly in the commanding heights of culture. Its return to power in Washington won’t be the salvation of American pluralism; it will be the unification of cultural and political power under a single banner.

Wielding that power in a way that doesn’t just seed another backlash requires both vision and restraint. And seeing its current enemy clearly, as a feckless tribune for the discontented rather than an autocratic menace, is essential to the wisdom that a Biden presidency needs.

On December 12, Douthat started with some light both-sidesism—“The widespread Republican belief in voter fraud is akin to the widespread Democratic belief that Russian hacking changed vote totals”—and then suggested that online extremism of the type pushed by Republicans following the election, might actually be—this is his exact term— a “stabilizing force”:

One possibility, which I explored in my recent book, is that political fantasy can actually be a substitute for radical action in the real world. There are ways in which the internet, especially, seems to contain and redirect the same extremism it nurtures — pushing it into memes and hashtags and social-media wars rather than actual revolutions, giving us Diamond and Silk tweeting about a military coup rather than the thing itself.

The fact that the government did not fall seems to have confirmed to Douthat that he was correct. Here he is last week.

This pessimism is, in a way, an extension of the arguments that went on throughout the Trump presidency, about how great a threat to democracy his authoritarian posturing really posed. As a voice on the less-alarmist side, I don’t think I was wrong about the practical limits on Trump’s power seeking: For all his postelection madness, he never came close to getting the institutional support, from the courts or Republican governors or, for that matter, Mitch McConnell, that he would have needed to even begin a process that could have overturned the result. Jan. 6 was a travesty and tragedy, but its deadly futility illustrated Trumpian weakness more than illiberal strength.

While Douthat was tap-tap-tapping away at his keyboard last winter, General Mark Milley, the chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, was organizing with other high-ranking officers a plan to prevent the president of the United States from carrying out a coup d’etat.

This episode is detailed in Carol Leonnig and Philip Rucker’s new book. Here’s a summary from CNN:

The top US military officer, Chairman of the Joint Chiefs Gen. Mark Milley, was so shaken that then-President Donald Trump and his allies might attempt a coup or take other dangerous or illegal measures after the November election that Milley and other top officials informally planned for different ways to stop Trump, according to excerpts of an upcoming book obtained by CNN.

The book, from Pulitzer Prize-winning Washington Post reporters Carol Leonnig and Philip Rucker, describes how Milley and the other Joint Chiefs discussed a plan to resign, one-by-one, rather than carry out orders from Trump that they considered to be illegal, dangerous or ill-advised. . . .

The book recounts how for the first time in modern US history the nation's top military officer, whose role is to advise the president, was preparing for a showdown with the commander in chief because he feared a coup attempt after Trump lost the November election.

The authors explain Milley's growing concerns that personnel moves that put Trump acolytes in positions of power at the Pentagon after the November 2020 election, including the firing of Defense Secretary Mark Esper and the resignation of Attorney General William Barr, were the sign of something sinister to come.

Milley spoke to friends, lawmakers and colleagues about the threat of a coup, and the Joint Chiefs chairman felt he had to be "on guard" for what might come.

"They may try, but they're not going to f**king succeed," Milley told his deputies, according to the authors. "You can't do this without the military. You can't do this without the CIA and the FBI. We're the guys with the guns."

In the days leading up to January 6, Leonnig and Rucker write, Milley was worried about Trump's call to action. "Milley told his staff that he believed Trump was stoking unrest, possibly in hopes of an excuse to invoke the Insurrection Act and call out the military."

Milley viewed Trump as "the classic authoritarian leader with nothing to lose," the authors write, and he saw parallels between Adolf Hitler's rhetoric as a victim and savior and Trump's false claims of election fraud.

"This is a Reichstag moment," Milley told aides, according to the book. "The gospel of the Führer."

That was the assessment of the chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff—not some silly Never Trump catastrophist. We’re talking about a man who was appointed by Trump and connected to the highest levels of the executive branch and had frequent, up-close exposure to the president.

So maybe the biggest threat to American democracy wasn’t coming from the liberals.

Maybe all of the lying and online shit-stirring wasn’t stabilizing.

Maybe this leader wasn’t just a “feckless tribune” and his followers were not merely “the discontented.”

Maybe the incompetent clown really was a danger to the Republic.

The most generous way to sum up Douthat’s work over the last year is that it was motivated wishcasting and that reading it would not have added to your understanding of what was happening in the real world.

The big question is: Why? How can someone be so wrong, so often, without ever reassessing his priors?

2. The Roots of Self-Delusion

Douthat often talks about “populism” as if the word signifies nothing more than a series of tax-policy decisions designed to bring relief to working- and middle-class families.

But if that were the case, he’d be a Biden stan. Have you seen what’s in the American Rescue Plan?

This month the government started sending checks to families with kids and I am here to tell you that this program is going to make a big difference in the day-to-day lives of working families, from the working poor all the way to the upper-middle-class.

The ARP is probably the most “populist” piece of pro-family legislation passed in a generation.

In the time since its passage, Douthat has written about the excesses of the anti-racism movement, the critical importance of the lab-leak theory, Michel Foucalt, how terrible “wokeness” is, how the Biden presidency could fail, very bad anti-Trump idols, and liberal hypocrisy when it comes to book publishing.

He has not yet gotten around to the ARP’s child tax credit payments.

On the other hand, Douthat sometimes talks about populism as a cultural matter, totally divorced from policies the government can enact. In this mode, he seems to mean woke-ism, local school board decisions, and the like.

Yet one of the many lessons taught by the last five years is that you can’t have “cultural populism” that is limited to the faculty-lounge definitions of liberal toleration. Real cultural populism—the stuff that gets people’s blood up and is strong enough to power a political movement—is always going to be crazy. It’s going to be conspiracies and lies and deadly anti-vaxxing and frazzledrip. Not to mention racism and political violence.

These traits are inextricably linked.

Would you like to know why Republican voters got super-duper excited by Donald Trump’s version of cultural populism and not Rick Santorum’s? It’s because Santorum didn’t talk about punching his opponents.

This stuff isn’t a regrettable follow-on effect of populism performed sub-optimally by an incompetent clown. It’s the straight juice. This is what “cultural populism” means in practice.

At this point, the only explanation for not understanding these linkages is not wanting to.

3. Private Army

A longread about Erik Prince from Time:

On the second night of his visit to Kyiv, Erik Prince had a dinner date on his agenda. A few of his Ukrainian associates had arranged to meet the American billionaire at the Vodka Grill that evening, Feb. 23, 2020. The choice of venue seemed unusual. The Vodka Grill, a since-defunct nightclub next to a KFC franchise in a rough part of town, rarely saw patrons as powerful as Prince.

As the party got seated inside a private karaoke room on the second floor, Igor Novikov, who was then a top adviser to Ukraine’s President, remembers feeling a little nervous. He had done some reading about Blackwater, the private military company Prince had founded in 1997, and he knew about the massacre its troops had perpetrated during the U.S. war in Iraq. Coming face to face that night with the world’s most prominent soldier of fortune, Novikov remembers thinking: “What does this guy want from us?”

It soon became clear that Prince wanted a lot from Ukraine. According to interviews with close associates and confidential documents detailing his ambitions, Prince hoped to hire Ukraine’s combat veterans into a private military company. Prince also wanted a big piece of Ukraine’s military-industrial complex, including factories that make engines for fighter jets and helicopters. His full plan, dated June 2020 and obtained exclusively by TIME this spring, includes a “roadmap” for the creation of a “vertically integrated aviation defense consortium” that could bring $10 billion in revenues and investment.

Don’t forget: Thursday Night Bulwark is tonight at 8:00 p.m.