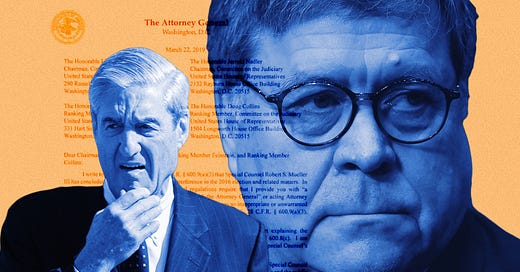

After two years, the Mueller report is finished, and almost everything we’ve heard about it so far is good news for President Trump. The twin drumbeats of the president’s Russia defense have been “no collusion, no obstruction”; in a Sunday letter to Congress summarizing Mueller’s findings, Attorney General William Barr largely affirmed the former and suggested that Trump would at least face no legal jeopardy for the latter.

The special counsel, Barr said, “did not draw a conclusion—one way or the other—as to whether the examined conduct constituted obstruction.” He went on: “Deputy Attorney General Rod Rosenstein and I have concluded that the evidence developed during the Special Counsel’s investigation is not sufficient to establish that the President committed an obstruction-of-justice offense.”

It’s pretty much been one big party for Trump and his allies since, and it’s not hard to see why. Sure, Barr’s laconic summary wasn’t the “TOTAL EXONERATION!” the White House is trumpeting, but it’s a lot closer to that than to the heads-will-roll collusion hopes that haunted the fever dreams of the most resistant Resisters. Mueller will not march into the White House and drag Trump out by the hair. If you’re a “CNN Sucks” type, what’s not to love? Finally, finally, the media will have to reckon with the ways in which they’ve become complicit in the machinations of the Loony Left—won’t they?

Amid all the celebrating and saber-rattling, however, the president’s allies may be missing a problem.

On the left, a counter-narrative is already forming. For many observers, the big story Saturday wasn’t that Mueller’s investigation cleared the president. It was that the Trump appointee who summarized the report, Attorney General William Barr, had apparently gone out of his way to frame Mueller’s findings as positively for the president as possible.

Many Democrats have seen Barr as a suspicious character ever since Trump nominated him to replace Jeff Sessions.

And not wholly without reason: After all, Trump fired the last guy, Jeff Sessions, because he didn’t throw his weight around enough at the Justice Department to get Mueller off his back. Didn’t it stand to reason that Trump would be sure to pick someone who’d be more loyal? Wasn’t it a little too coincidental, perhaps, that he happened to pick Barr, a guy who the summer before had sent a letter to top Justice Department brass arguing that an obstruction charge against Trump for firing former FBI Director James Comey would constitute “a novel and legally insupportable reading of the law” that “would do lasting damage to the Presidency and to the administration of law within the Executive branch”?

In Barr’s Sunday letter, many Democrats thought they saw their worst fears confirmed. Here was Mueller suggesting the evidence surrounding a potential obstruction case is at least strong enough to suggest that an obstruction case is a tough call. And then there was Barr, coming out of left field to say there’s no obstruction case to be had. The fix was in!

Is there anything to the argument? Eventually we are likely to know the truth. But until then, consider this: Barr is a longtime public servant who has little to gain from sucking up to Trump. He comported himself well during his confirmation hearings. And for him to misrepresent Mueller's findings would be risking his entire career and reputation on a gambit that (a) doesn't do anything of substance and (b) is completely falsifiable.

If Barr was playing fast and loose with his interpretation and the report eventually gets out, he'd be cooked. The report could come out through the congressional process. It could be leaked by anyone on Mueller's team. And if Mueller thinks Barr is trying to distort his work, two former federal prosecutors told The Bulwark Monday, there would probably be nothing to prevent him from speaking out himself.

“I am quite confident that if General Barr did mischaracterize the special counsel’s views,” former prosecutor John Malcolm said, “the special counsel would say so. . . . So I would take his silence as a tacit approval of the accuracy of the summary of Bill Barr, and there is no reason at all to question the accuracy of that summary.”

But all this is almost beside the point. The circumstantial evidence Democrats have arrayed against Barr will introduce just enough uncertainty into the equation to convince those who long to see a cover-up. If this continues, the unhappy result will be that the report achieves nothing but a further sorting of the populace into political silos. The Mueller investigation is the great political controversy of our time. (This week, at least.) If there’s any way that further sorting can be avoided on the subject, that would be a public good.

The release of the Mueller report, even if heavily redacted, would help. The less satisfying the results of Mueller’s investigation are to Trump’s resistance critics, the more crucial it will be for them to hear those results straight from the mouth, as it were, of the man in whom they have long invested their hopes.

But there’s one last simple step Mueller could take that may help as well. The special counsel has shown no plans to do anything besides simply allow his work to speak for himself and fade quietly back into private life. He has shown admirable restraint in letting Barr do the talking for him. When the report does drop, however, there’s nothing to prevent Mueller from releasing a simple statement endorsing Barr’s redacted version as a faithful representation of his work, if indeed it is.

Should such a step be necessary? In a saner world, probably not. And even to suggest it would help is, perhaps, unfair to Barr. Malcolm suggested that Mueller might not speak up for precisely that reason: “I actually believe that if Mueller were to come out with a statement saying, ‘Everything Bill Barr says is entirely accurate,’ that would suggest or imply that there was reason to doubt the accuracy of what Bill Barr said. . . . As far as I'm concerned, Bob Mueller does not need to say what should be obvious.”

What we have to work with today, however, is a politics waterlogged with partisan fear and distrust. If one of the goals of the Mueller report is to counteract that distrust—to close the book on the Russia affair in a way that supplies us at least some common ground for understanding it going forward—then it is crucial that the messenger not be distrusted.

One last time, it seems, the country may need Robert Mueller.