Software Is Eating Democracy

We have to get smart about the risks of even "good" AI.

1. Speed

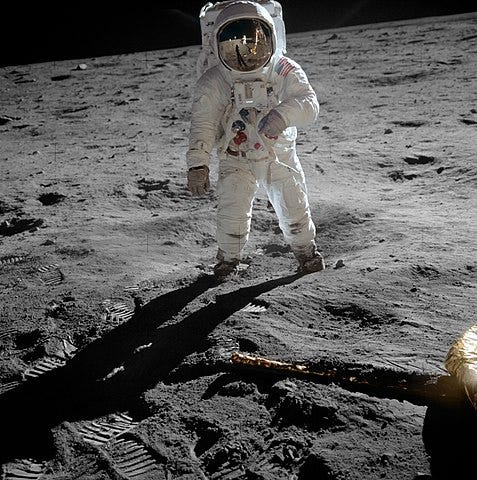

Here is a photo of the first controlled flight—it’s the Wright Brothers in 1903:

Here’s where that moment led to in 1969:

That’s 66 years of progress. Imagine you were 10 years old standing around at Kitty Hawk and I told you that before you died, this flimsy, two-wing, half-glider would evolve into a rocket ship that would put a man on the moon. Would you have believed me?

Technology can advance at a terrifying pace.

Not always. We are 124 years into the Age of the Zipper yet the zipper on your jacket is pretty much the same thing we saw in 1909. But maybe you don’t think of zippers as technology.

Let’s look at cars.

The first car dates to around 1800. It was a steam-powered curio and it took almost a century to get to something approximating a modern car—a mass-produced vehicle with an internal combustion engine.

The modern automobile is significantly different from all of those early vehicles. However the differences are evolutionary, not revolutionary: Bigger, faster, cheaper, with different forms of fuel and advanced safety, sure. But even 220 years in, these vehicles are foundationally the same: Powered conveyances designed to carry individuals through two-dimensional space.

Point being: Not all technology undergoes rapid, revolutionary change.

So which one is AI? Is it flight or the automobile?

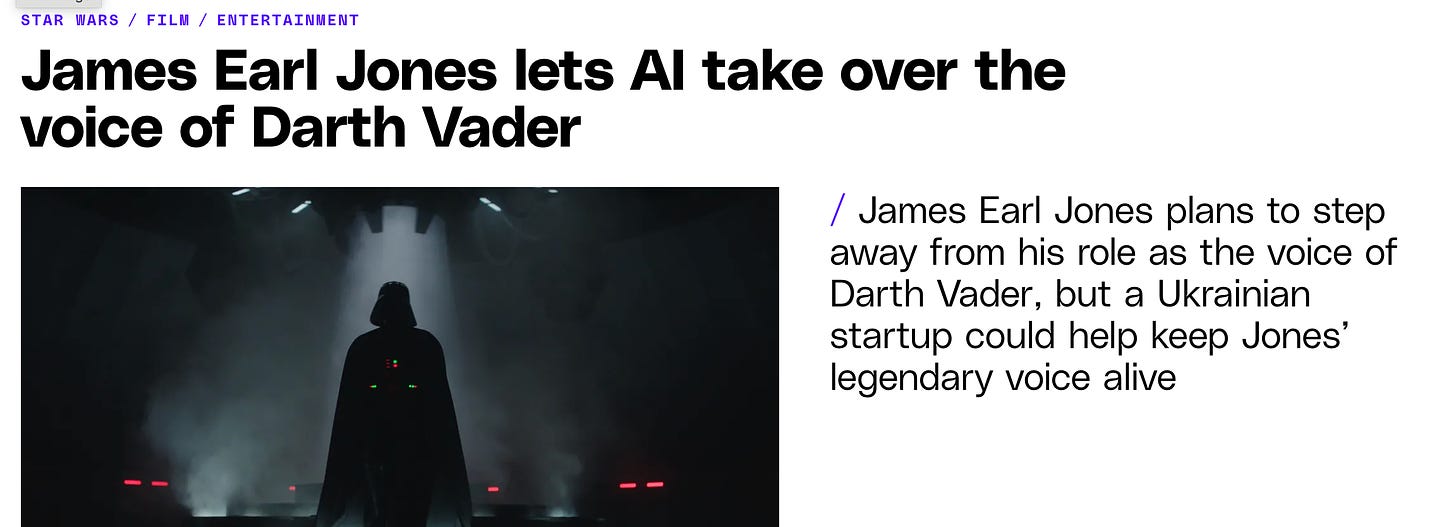

The first networked computer system was ARPANET, built in 1969. Over the last 54 years we’ve gone from a computing network that could transfer small files between remotely connected terminals to this:

Yes, I know. Having AI mimic Darth Vader is small beer. What I want you to focus on is the speed. We’re only 54 years into the era of networked computers. AI is much more likely to be a revolutionary technology (like controlled flight) than an evolutionary technology (like the car).

And revolutionary technologies move incredibly fast.

Tim talked about AI with Scott Galloway last week and their conversation is very much worth your time.

Galloway is bullish on AI. He believes that AI advances will increase productivity, add value, and (eventually) create more jobs than they destroy. He believes that some sectors will see tremendous benefits from AI—particularly healthcare.

I’m willing to believe much of that. Certainly healthcare is the most promising place for AI. The prospect of AI assisting in radiology, for example, could be extremely valuable. Ditto drug development.

But there are two large-scale risks AI presents to the liberal order.1

The first is labor displacement. Let’s pretend that AI creates another economic revolution. How fast will that revolution proceed?

Pretty damn fast. Probably faster than the Industrial Revolution took hold.

Fast revolutions cause more displacement because they deny existing systems time to adapt. So even if, in the medium-run, AI creates more jobs than it destroys, the short-run is important, too.

Because labor displacement leads to social unrest and political instability. I’m not sure how much slack our society has right now to absorb any more of those.2

The second risk is more specific and Galloway talks about it at some length with Tim: In Q1 and Q2 of 2024, we are likely to see massive efforts from the Russians and Chinese to leverage AI into helping Donald Trump become president again.

It is not clear to me that either the media or the American citizenry is prepared to deal with the impact of AI on a presidential election.

2. Complacency

Techno-optimism is one thing. Techno-complacency is another.

A dozen years ago Marc Andreesen noted that “software is eating the world.” What he meant is that computer software was touching every aspect of our lives: From how the internal systems of our cars worked to how we rented hotel rooms, or bought books, or found mates, or hailed taxis.

Here’s Andreesen:

Six decades into the computer revolution, four decades since the invention of the microprocessor, and two decades into the rise of the modern Internet, all of the technology required to transform industries through software finally works and can be widely delivered at global scale.

Andreesen’s observation was correct.

What nobody thought to ask was: Will software also eat democracy and/or the liberal order?

Or to put it another way: Why would democratic institutions and the liberal order be immune to the effects of this revolution when literally no other aspect of society has been?

AI is a toy today. It’s the chatbot that answers questions with varying degrees of accuracy. It’s a picture-maker. It’s an audio-processing algorithm. It can mimic Darth Vader.

But we’re in the early stages and the technology is moving fast. We can already see some of the risks. Others will become clear as AI develops and deploys further. Still others won’t reveal themselves until we’re already in the midst of a problem.

Sure, maybe AI won’t eat the world, too.

But I wouldn’t bet against it.

Every day I try to help you see around corners. Things may seem fine today, but we are on a collision course illiberalism. I’m trying to guide our thinking and wrap our heads around this reality, right now. Bulwark+ members help to sustain our work and make it available to the widest possible audience. Upgrade today to join our community.

You can cancel any time.

3. Gun Guy

Pro Publica profiles the man who made the AR-15 into a industry.

When the public asks, “How did we get here?” after each mass shooting, the answer goes beyond National Rifle Association lobbyists and Second Amendment zealots. It lies in large measure with the strategies of firearms executives like [Richard E.] Dyke. Long before his competitors, the mercurial showman saw the profits in a product that tapped into Americans’ primal fears, and he pulled the mundane levers of American business and politics to get what he wanted.

Dyke brought the AR-15 semi-automatic rifle, which had been considered taboo to market to civilians, into general circulation, and helped keep it there. A folksy turnaround artist who spun all manner of companies into gold, he bought a failing gun maker for $241,000 and built it over more than a quarter-century into a $76 million business producing 9,000 guns a month. Bushmaster, which operated out of a facility just 30 miles from the Lewiston massacre, was the nation’s leading seller of AR-15s for nearly a decade. It also made Dyke rich. He owned at least four homes, a $315,000 Rolls Royce and a helicopter, in which he enjoyed landing on the lawn of his alma mater, Husson University.

Although his boasts of military exploits and clandestine derring-do caused associates to roll their eyes, he was actually no gun enthusiast. As a teenager, he dreamed of becoming a professional dancer. Once, when his brother Bruce persuaded him to go deer hunting, Dyke sat in his Jeep reading The Wall Street Journal, rifle out of reach as a deer ambled safely past.

Along the way, Dyke and his team capitalized on the very incidents that horrified the nation. Sales typically went up when a mass killer used a Bushmaster. After a pair of snipers in the Washington, D.C., area murdered 10 people with a Bushmaster rifle in 2002, Dyke’s bankers noted that the shootings, while “obviously an unfortunate incident … dramatically increased awareness of the Bushmaster product and its accuracy.”

For the sake of this discussion we’re going to assume that both the forms of AI we have now and any AGI we create won’t be appocalyptic world destroyers.

Maybe we shouldn’t stipulate to that! But that’s a different conversation. So just roll with me.

We are 30 years after NAFTA and the political and social instability created by the birth of a globalized economy is still increasing. Not great, Bob.

As someone who's failed at both technology (computer science degree, numerous jobs at startups software engineering, all of them fell through and I now work in a warehouse) and at the law (completed two years of law school and got 140K$ of student debt in the process without a degree to show for it), let me try to harness my experience in both to talk about evolutionary and revolutionary changes in law and technology.

One of the unifying principles of the law is that there is no 'law of the horse' - that is to say, the same general rules that apply to cases around horses apply to cases around cars. This is because our laws are made for people, not for cars or horses. People have an interest in not being hit by runaway horses, people have the exact same interest in not being hit by cars. People have an interest in not being scammed when they buy a car to be given something that they claim is new but is actually a beat-up old Ford that's been freshly painted, and people have the same interest in not being defrauded by being sold a racing thoroughbred as the secret grandson of Secretariat that is actually a random horse the person found behind the barn shed.

The exact implementation and details of how these interests are protected may vary - horses do not require headlights and generally do not require posted speed limits. But the interests, the things that we are trying to protect the person against, remain the same. The sort of mischief that the law intends to manage has remained fairly constant over centuries, even as capabilities change around it. War may have changed, but war never changes.

Now, sometimes revolutionary technologies, never thought of when a specific law or specific principle was originally come up with, may change exactly how the implementation of the law protects those interests. The 'ad coelum' doctrine, which stated that a property owner also owned all of the air above their property and the ground beneath it, was originally stated in the thirteenth century by Accursius, who phrased it in Latin as 'whoever's is the soil, it is theirs all the way to Heaven and all the way to Hell'. And this worked fine for protecting all the interests of people involved, until the invention of the passenger aircraft, which by flying overhead, was trespassing on several different private properties each second.

Did we have to throw out all of our old law? No, we simply reinterpreted it - the 'ad coelum' doctrine wasn't meant to give you the ability to sue planes or trained birds for flying overhead, it was meant to protect your interest in being able to mine underneath your property or build as tall as physical engineering permitted you to. Those interests could still be protected while allowing planes to fly overhead without trouble. Focus on the interests, not on the implementation, and the basic rules will remain constant.

What's the 'law of the AI'? Is AI really the problem? AI, the Russians, the Chinese, I see all of these things as an attention-grabbing distraction, something that's new and thus newsworthy. The interests that people have are getting accurate information about the world around them. But remember the sophisticated people on the National Review cruise you mentioned, JVL, the ones who were enraptured by the story that Barack Obama's secret gay lover was about to reveal himself? The ones who were horrendously upset with you when you pointed out that that wasn't going to happen and never was going to happen, that they were all circulating a lie about their political enemies that made them feel good but was clearly false?

The problem isn't AI. The problem is that we have a huge chunk of the population who doesn't want accurate information. That problem is going to stay with us whether the fakes created are perfect simulacra of reality crafted in a Chinese research laboratory, or a hastily-made photoshop from catpuncher420 on Twitter.

I'm not at all afraid of what AI is going to do come 2024. I'm absolutely terrified of what a huge chunk of the population, a chunk of the population that hates their political enemies so much and cares so little about whether or not what they're hearing is true that Fox News was willing to pay 767 million dollars rather than disagree with them, is going to do. And they're going to do that whether or not artificial intelligence is an evolutionary or a revolutionary technology. They'd do that if artificial intelligence didn't even exist.

The problem isn't AI. The problem is the people.

As you always say.

<quote>AI is a toy today.</quote>

I hate correcting you but the technically correct phrase is "The AI that you see is a toy today."

The stuff in the labs stays out of the public eye for a good reason. For example, is AI that could handle stock trading strategies. Not the stuff Wells Fargo tells you about when you check your balance or get money from the ATM. Stuff that's being run in data centers that don't have an address or signage. Data centers that are blurred out on Google Street View. Data centers with ten feet of fence topped with concertina wire.

And don't even ask about the NSA's data center in Utah...