LET’S START WITH THE OBVIOUS: Slavery is not a “both sides” or a “yes, but” question. While one may debate specific issues—was it an integral part of the American founding or a pernicious legacy of the British colonial system?—none of that changes the fundamental fact: The ownership and trafficking of human beings was an atrocity, a stain on a country that proclaimed liberty to be its foundational principle.

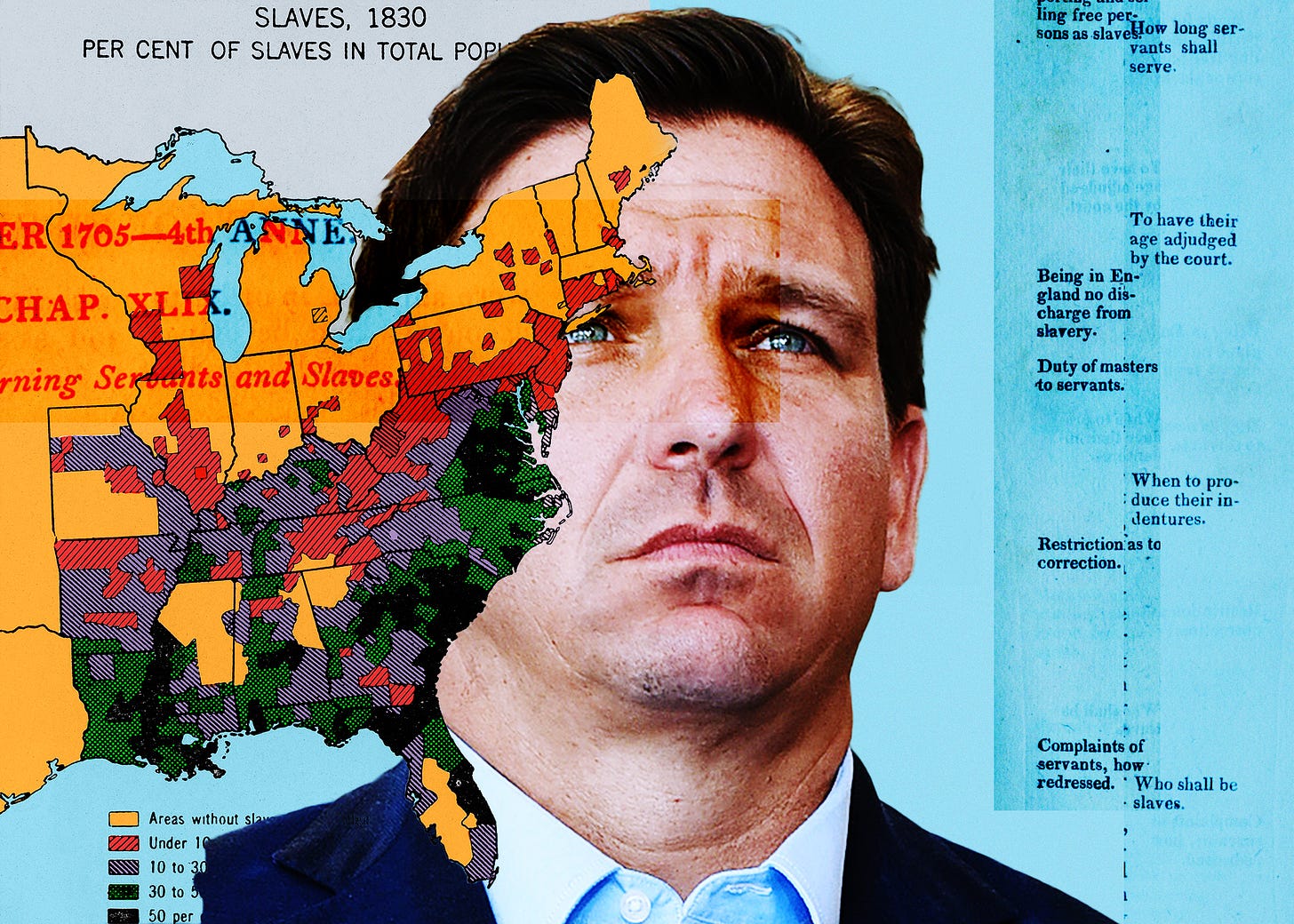

On the other hand, the flap over the newly approved Florida school standards for the teaching of African-American history is a “both sides” story, and one in which neither side looks very good. Not only the left but mainstream liberals—including major media outlets and Vice President Kamala Harris—joined in a frenzy of denunciations over a line very misleadingly summarized as a claim that “enslaved people benefited from slavery” because some of them learned useful work skills. But while the Florida curriculum doesn’t say that, or suggest that American slavery was not so bad, it does have very real problems. What’s more, Harris’s essentially false and inflammatory accusation was matched by an incredibly ham-fisted response from Florida Governor Ron DeSantis and an apparent major stumble by the standards’ principal authors.

Add to this a lot of all-around self-beclownment in the media, and it’s “The Culture Wars Make Everyone (and Everything) Dumber,” Chapter Eleventy-Thousand Eleven.

SO WHAT DOES Florida’s new African-American history curriculum, approved by the state board of education on July 19 as part of a larger set of social studies curricular standards, actually say? (While some commentators have claimed that the disputed line has been picked out of 216 pages of text, this is the length of the entire document, including dual listings of the same items; the African-American history strand per se is about 20 pages.) Read in its entirety, this curriculum certainly doesn’t suggest slavery apologia. Some of the material that compellingly exposes racial oppression in American history may not be immediately apparent because it hides behind the dry names of laws and codes. For instance, a high school unit on the development of labor systems in colonial America has a “clarification” noting, “Instruction includes the Virginia Code Regarding Slaves and Servants (1705).” This code (actually named “An act concerning Servants and Slaves”) makes starkly clear the establishment of an oppressive racial hierarchy: Indentured servants, nearly always white, have certain rights and protections as well as the prospect of eventual freedom; slaves, nearly always black, are stripped of all rights. Even the killing of a slave by a master has no consequences if it’s blamed on the slave resisting “correction.”

Another new curriculum unit, which focuses on “how conditions for Africans changed in colonial North America from 1619-1776,” includes “clarifications” that the lessons must include the development of slave codes and “how slave codes resulted in an enslaved person becoming property with no rights.” Several units focus on slave revolts and how “slave codes were strengthened in response to Africans’ resistance to slavery.” There are also discussions of the passage from Africa, of “harsh conditions and their consequences on British American plantations,” of how the Founding-era legislation and the Constitution dealt with slavery, and of nineteenth-century efforts to aid fugitives from slavery and the South’s attempts to stop these efforts. Several units focus on abolitionist narratives by former slaves, including Sojourner Truth and Frederick Douglass—narratives from which no sane person could come away with the impression that there was anything benevolent about American slavery. (Sojourner Truth endured brutal beatings and rapes before she gained her freedom.)

So what’s that controversial line—a “clarification” requiring students to be taught about “how slaves developed skills which, in some instances, could be applied for their personal benefit”—doing in there?

It is clear that the intent of the unit in which the disputed line appears is to show the wide range of jobs performed by slaves, countering the common assumption that they were all either field hands or domestic servants. Such information is already commonly found in educational texts. The “personal benefit” line is presumably intended to convey that sometimes slaves also managed to use those skills for themselves: to earn a living if they gained their freedom, or even, on occasion, to free themselves. Enslaved skilled workers hired out by their owners were sometimes able to keep and save enough of their earnings to buy their freedom. While some left-leaning polemicists in the brouhaha over the Florida standards dismissed this scenario as a fantasy, it did happen—albeit rarely, and despite formidable obstacles (more on that below).

According to a statement from two members of Florida’s all-volunteer African American History Standards Workgroup—Michigan State University professor emeritus and former U.S. Civil Rights Commission chairman William B. Allen and lawyer/author Frances Presley Rice—the “clarification” is intended to underscore the “strength, courage and resiliency” of African Americans rather than “reduce slaves to just victim of oppression.” Or, to put it differently, it’s a way to emphasize the agency of the enslaved, the standard perspective in progressive scholarship in recent decades.

Incorporating such a framework into lessons for kids can be dicey: one has to walk a fine line between presenting slaves as just victims and implying that slavery wasn’t so bad.

Arguably, the passage in the Florida curriculum was clumsily worded. But to render it as “slaves could benefit from being enslaved” or “slavery helped slaves develop useful skills” is an extremely tendentious reading, or even misreading: the reference is to benefiting from skills, not from slavery. (If an article says that some cancer survivors have had their lives enriched by the interests and hobbies they developed as a coping strategy during treatment, that’s not tantamount to saying that cancer enriched their lives.) Surely, the more plausible meaning is that some slaves used their resourcefulness, talent, and tenacity to make the best of a terrible, oppressive situation.

The remarkable life of abolitionist and author Moses Grandy illustrates this point. Born into slavery around 1786, he was hired out starting at the age of 10 to employers who would sometimes beat him and half-starve him. Nevertheless, Grandy managed to become a highly skilled boat navigator and eventually a captain and was able to keep a portion of his earnings. He started saving money, having been promised his freedom for $600 (about $15,000 in today’s currency)—but after the final installment was paid, the slaveholder simply pocketed the money and reneged on his promise. (The slaveholder’s sister and brother-in-law went to court to force him to honor the agreement, but their efforts were futile.) Sold to someone else, Grandy negotiated the same deal, only to be cheated again. Finally, another man who had been told about Grandy’s plight bought him and set him free, and he was eventually able to purchase the freedom of his wife, several of his eleven children, and some of his siblings. By the time he gained his freedom, he had suffered unimaginable heartbreak, losing his father, his beloved first wife—who was literally snatched away before his eyes—and at least five children to legalized human trafficking.

To suggest that Grandy benefited from slavery would have been obscene. Had he been born at the same time and in the same place as a free man, even a free black man in early nineteenth-century America, his life would have been immeasurably better, and he could have used his skills as a navigator to become a wealthy man instead of spending thousands of dollars to ransom his family. Even so, there is no question that he used the skills he acquired while enslaved for his personal benefit—not because of but in spite of slavery.

TO A LARGE EXTENT, the outrage over that one line in the Florida curriculum rests on the knee-jerk assumption that it must be intended to justify white supremacy, because . . . well, because it comes from Ron DeSantis and the Florida Republicans.

Yet the truth is that you can easily find passages in blue-state African-American history curricula that, if taken out of context and prejudged as slavery apologetics, could trigger outrage. Take a New Jersey curriculum unit which discusses the complex dynamics of slavery and says that “its practictioners [sic] inevitably had to accommodate the basic humanity of the bondsmen”: One could, if so inclined, sum it up as “Enslavers always respected the humanity of the enslaved.” Or think what a scandalous spin one could put on a Library of Congress classroom guide which says that slaves “put their hands to virtually every type of labor” and “plied their own specialized skills” in a wide variety of tasks: Doesn’t this make slavery sound like a jobs program and minimize the coerciveness of slave labor?

So yes, conservatives have a point when they charge that the Florida curriculum, compiled by a 13-member workgroup that reportedly includes six black Americans, is being unfairly maligned and demonized. The Florida curriculum is not a rehash of the learning materials often used in the South until recently that portrayed American slavery as relatively benign and stressed quasi-familial devotion between slaves and masters; to the extent that it tries to be “positive,” its positivity chiefly resides in its heavy focus on abolitionism and on the accomplishments of free blacks. Nor is it an attempt to whitewash, as it were, Jim Crow (there are units focusing on the post-Reconstruction disenfranchisement of newly emancipated blacks and on white resistance to black equality, including the Ku Klux Klan, and African Americans’ struggle against racism). The Civil Rights movement of the 1960s is celebrated to such an extent that a guidance for second graders names “Rosa Parks and Thomas Jefferson” as “individuals who represent the United States”—an odd pairing, but certainly not one coming from an anti-civil-rights mindset. It’s not only conservatives who have criticized the tempest over the line about “skills” as excessive and misplaced; such critics also include, for instance, liberal blogger Kevin Drum.

That said, the curriculum does have its issues. As Drum points out, it definitely deemphasizes the brutality of slavery; there is no mention of the wrenching and fairly common practice of family separation, of the ever-present threat of physical punishment, or of the widespread sexual exploitation of female slaves. One could counter that many of these things are covered by the materials whose study is required in the curriculum, such as the ex-slave narratives and the slave codes that prescribe punishment by whipping for various infractions (and, as previously mentioned, essentially legalize the murder of the enslaved). But it’s worth noting that while the curriculum has many “clarifications” that mention the study of specific topics—such as the use of work skills for “personal benefit”—there are no such items mandating discussion of sexual violence, surely an age-appropriate subject for high school students, or of the forcible disruption of families. Likewise, lynchings are mentioned in only one unit on the “emergence, growth, destruction and rebuilding of black communities during Reconstruction and beyond.” The same unit, by the way, contains a “clarification” line that really does legitimately raise eyebrows:

Instruction includes acts of violence perpetrated against and by African Americans but is not limited to 1906 Atlanta Race Riot, 1919 Washington, D.C. Race Riot, 1920 Ocoee Massacre, 1921 Tulsa Massacre and the 1923 Rosewood Massacre.

All the events listed here are violent assaults against African Americans. Just what “against and by” is supposed to mean is unclear; if it’s a reference to black self-defense against racial terrorism, then it’s either mind-boggling sloppiness or truly appalling moral equivalency.

Blogger Josh Marshall has also noted that the curriculum strongly emphasizes what he calls “other societies that practiced slavery and other places where slavery was arguably worse”—such as the existence of slavery and the slave trade in Africa before the European slave trade began, as well as slavery in the Caribbean islands (where labor was much harder and mortality rates were staggering) and in Central and South America. As Marshall notes, all of this is factual. Teaching these facts is valid; many young progressives raised on modern anti-racist activism seem to believe that slavery makes the United States uniquely evil, or that white people invented slavery. It’s important to put American slavery in global perspective (in which it is sometimes less and sometimes more inhumane than other forms of enslavement). But it’s also important to do so in a context that doesn’t lend itself to an “it wasn’t so bad” message. One could point out, for instance, that most other slave-owning cultures did not have the same hypocrisy problem, since they did not profess to believe that “all men are created equal” and that liberty is an unalienable right.

One may add that while the Florida curriculum wants to spread the blame for slavery, it doesn’t want to spread the credit for its abolition: the British abolitionist movement and its role in ending the slave trade rate no mention, and neither does the abolition of slavery in the British colonies thirty years before the American Civil War. (The only exception: two mentions of instances in which the British offered liberation to slaves in America as a strategy in military conflicts, in the Revolutionary War and the War of 1812.)

In other words, while this is not a curriculum that justifies or denies slavery or white supremacy, it is definitely one that tends to accentuate the positive in African American history, and more generally American goodness: abolition, the civil rights movement, the lives of free blacks, thriving and self-sufficient black communities, African-American heroes and cultural figures. Of course those are important things to learn; but such an approach can also result in a skewed rosy picture that reduces the oppression and atrocities to “bad stuff happened, but let’s look at how we got over it.” Yes, it’s pushback against a tendency on the left to treat racism and the legacy of slavery as America’s defining features; but it’s an overcorrection.

Lastly, on at least one occasion, the Florida curriculum takes a dive into blatant partisanship. In a high school unit on “the politicians and political figures who advanced American equality and representative democracy,” a “clarification” on “political figures who shaped the modern Civil Rights efforts” offers the following examples: “Arthur Allen Fletcher, President Dwight D. Eisenhower, President John F. Kennedy, President Lyndon B. Johnson, President Richard Nixon, Senator Everett Dirksen, Mary McLeod Bethune, Shelby Steele, Thomas Sowell, Representative John Lewis.” Even leaving aside the Republican/Democrat balance on this list: I’m sorry, but Thomas Sowell and Shelby Steele? Both are important and interesting figures, and if they were mentioned in a unit dealing with intellectual debates and controversies related to race, they would not be out of place. But on a list of figures “who shaped the modern Civil Rights efforts,” their presence looks like a strange case of affirmative action for conservatives. (Is there a lot of left-wing bias in the educational system? Yes, there is. But once again, as with much of what DeSantis does, the supposed remedy promotes a different kind of bias instead of balance.)

To these problems, one can also add an apparent, stunning faux pas by Allen and Rice in their response to the critics of the curriculum. As a partial justification for the contested clause about some slaves developing skills from which they benefited, Allen and Rice listed examples of black Americans who supposedly did exactly that: used skills they learned while enslaved. Yet debunkers were quick to point out that nearly half of the people on the list had never even been slaves. (Most bizarrely, one name seems to refer to George Washington’s sister, a white slave owner.) In several cases, the list also attributed the wrong trade to the people cited.

When asked by Megyn Kelly on Tuesday about the debunkings, Allen was dismissive: “How many angels do dance on the head of a pin?” To the charge that several of the figures he and Rice cited were never even enslaved, Allen asserted nonresponsively that “the point is that people demonstrated their capacities and their accomplishments and that’s a story that must be told.” Indeed—but surely it must be told accurately.

Neither Allen nor Rice has as yet responded to a request for comment for this article.

LASTLY, THERE IS THE ROLE played in this controversy by Ron DeSantis, who, as writer Nick Catoggio points out, is a lightning rod for a reason. Even many people who heartily dislike “woke” progressivism cringe at his blatantly opportunistic “anti-woke” crusade that is every bit as self-righteous, ideologically crude, and prone to bullying as a lot of “woke” zealotry. What’s more, the “anti-woke” activists DeSantis champions do sometimes seem hostile to all strong critiques of past racism: see the objections to teaching the 2009 book Ruby Bridges Goes to School, written by Ruby Bridges herself—the woman who, back in 1960, became the first black child in a previously all-white New Orleans school. The book’s critics objected on the ground that its accurate depiction of an angry white mob was too negative and lacked “redemption”. That’s not the outlook of the Florida curriculum, which does mention Ruby Bridges along with other desegregation pioneers. But DeSantis, who rails at very broadly defined woke excess, has not exactly done much to distance himself from anti-woke excess; he’s the guy whose campaign promoted a video touting him as a “draconian” anti-LGBT warrior and has just fired a staffer who pushed a DeSantis video with Nazi imagery in it. Catoggio correctly points out that DeSantis hasn’t done much to earn the benefit of the doubt on culture-war issues.

DeSantis’s reaction to the curriculum controversy further reinforces that point. He mocked Vice President Harris for trying to “chirp and demagogue” the issue. He blithely waved aside the debate about the “skills” line in a dismissive comment (“They’re probably going to show . . . some of the folks that eventually parlayed being a blacksmith into doing things later, later in life”) without bothering to explain why the criticism was inaccurate. He could have talked about how abhorrent slavery was and how important it was to study not only its inhumanity but the humanity of people who overcame unthinkable obstacles to win their freedom. He could have, for instance, told the story of Moses Grandy. But somehow, it’s hard to imagine DeSantis doing that. His combative responses may have boosted him in the eyes of hardcore “anti-woke” voters for whom “own the libs” is the beginning and the end of conservatism, but they undoubtedly alienated mainstream voters.

What’s more, even as he dug in, DeSantis also tried to distance himself from the curriculum by stressing that he had nothing to do with it—eliciting a scathing rebuke from former New Jersey governor and GOP presidential candidate Chris Christie. He is, in other words, a culture-war chicken hawk.

Meanwhile, down in the trenches, the stupid thickens. Progressive pundits made sarcastic comparisons to the Holocaust, mockingly saying “some Jews also benefited from the skills they acquired shoveling other dead Jews into furnaces in Auschwitz.” Fox News anchor Greg Gutfeld ran with the analogy, asserting that Jews survived concentration camps by being useful. And for vast numbers of Americans, this saga will merely validate their polarizing political priors: that Republicans are so racist they actually want to rehabilitate slavery; or that Democrats are lying racial demagogues. What suffers most, unfortunately, is the possibility of civilized conversation on race in American history.