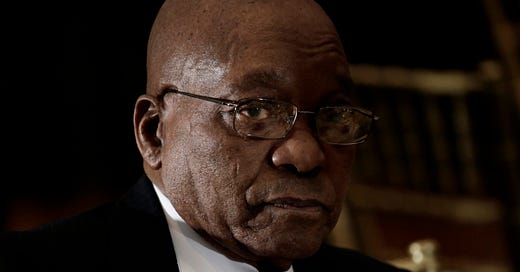

South Africa Had a Trump. They Handled Him Better.

The rise and fall of Jacob Zuma has lessons for the United States.

ONCE UPON A TIME, THERE WAS a very bad president who caused much harm to his country’s democracy. Even before he became president, he was credibly accused of theft, fraud, and sexual assault, but people thought he was entertaining and supported him anyway. As president, he used the government to enrich himself and his cronies. He elevated corrupt incompetents who drove institutions into the ground. His once-proud political party—cowed by his fanatical, tribal following—tolerated him for too long. He attacked his own party, the free press, government officials, the judiciary, and anyone who tried to keep him accountable, eroding public trust in democracy itself.

No, I’m not talking about Donald Trump, but rather his wily South African analog, Jacob Zuma, whose tenure as president from 2009 to 2018 presented an existential threat to the continent’s most solid democracy. The two men’s uncanny similarities made for some uncomfortable moments when I briefed Trump officials on Zuma during their overlapping terms.

There are some personal differences, of course. Zuma, with his second-grade education, is by far the more intelligent and accomplished. He was born into poverty and suffered for his country, serving time in Robben Island prison with Nelson Mandela for his role in the anti-apartheid struggle.

Also, Zuma is married to most of his wives simultaneously. He’s been married six times and currently has four wives and twenty-three children (not all of them with his wives). Unlike Trump, Zuma was criminally prosecuted (but acquitted) for rape. The alleged victim was his friend’s HIV-positive daughter, whom Zuma had known since she was a child. He claimed the encounter was consensual and a post-coital shower compensated for the unprotected sex.

But the main divergence of the Zuma and Trump stories is that South Africa’s democracy—just thirty years old—has responded better to its authoritarian threat than the world’s oldest, richest, most powerful democracy.

Zuma rose to power by skillful maneuvering within South Africa’s founding party, the African National Congress (ANC), which is so dominant that winning the party leadership race is tantamount to winning the presidency. Despite facing numerous potential charges for previous corruption, he was able to use his connections, clout, and knowledge of skeletons in closets (he was the former intelligence chief) to outfox the ANC’s “establishment” wing in 2007 party elections, followed by the presidential elections in 2009.

Zuma swept in on a populist wave of die-hard support from his ethnic Zulu community, a major political bloc. He effectively spun a persecution narrative to explain away his alleged crimes, while deftly playing on the (very real) frustrations and hardships of poor, black South Africans, as well as their racial, ethnic, and class prejudices. His demagoguing of immigration continues to fuel waves of violent, xenophobic attacks on refugees from other African nations.

AS PRESIDENT, ZUMA PURSUED SOME pro-poor policies. But mainly he pursued pro-Zuma ones. His first big, new scandal was the revelation in 2014 that he had availed himself of $23 million in government money to renovate his private home. Though the Constitutional Court eventually ordered him to repay some of the money, he largely weathered the political storm thanks to his fanatical following, and intimidation of his critics, and sheer shamelessness.

But the mother of all Zuma scandals involved his relationship with a wealthy Indian family, the Guptas, whom he allowed to “capture” the South African state to their mutual benefit. Starting in the 1990s, the two families over time became financially enmeshed, and when Zuma became president, they all cashed in.

In 2013, the Guptas used a South African military base to fly in dozens of guests for a nearby wedding.

Two years later, Zuma abruptly fired the respected finance minister, Nhlanhla Nene, and installed an unqualified ANC backbencher to replace him.

Nene’s firing unleashed near daily revelations in the South African press of the extent of the Guptas’ power. It turned out Nene was fired on their orders, and the Guptas had offered his job, along with suitcases of cash, to two other officials before finding someone unscrupulous enough to accept. They also brokered other cabinet posts and leadership of state-owned companies. The Gupta-approved head of South African Airways, one of Zuma’s lovers, all but ruined it with policies designed to boost the Guptas’ own airline and to siphon off cash from the government. In an effort to benefit Gupta energy ventures, the national electricity company’s board plunged it into catastrophic debt and dysfunction, denying millions of South Africans reliable power for years.

All told, the Guptas and the Zumas—which South African media cheekily dubbed the “Zuptas”—essentially set up a parallel, unelected, unaccountable state, with full control of law enforcement bodies, multiple state-owned companies, much of the ANC delegation in parliament, and some media outlets. The law enforcement apparatus was a particularly useful part of their portfolio, as the Zuptas could rely on a lack of accountability, even though South Africa’s stalwart judiciary blocked attempts to threaten Zuma’s enemies. The Guptas pocketed well over $2 billion in public funds, while the Zuma family reaped untold millions in goods, property, legal fees, and joint business. The damage to the South African economy was severe and possibly irreversible.

Unlike the Republican party, the ANC eventually got fed up. Voters did too, punishing the ANC in the 2016 municipal elections. Many educated and middle-class voters were tired of Zuma’s economic chaos. Other South Africans took their cues from the ANC’s revered anti-apartheid veterans, who publicly railed against Zuma’s excesses and led large demonstrations against him. Eventually, enough party officials, business leaders, and ordinary South Africans chose their country, and South Africa’s democracy, over Zuma. Zuma was forced to resign on February 14, 2018. His chosen successor (and ex-wife) failed to win the next party elections. Deputy President Cyril Ramaphosa, no angel but better than Zuma, was elected in his own right in 2019.

LIKE TRUMP, ZUMA IS A REMORSELESS narcissist who continues to menace South African society. But unlike Trump, he is more neutered politically, thanks to South African courts and the ANC, which expelled him for a short-term political cost. In 2021, the Constitutional Court found him guilty of contempt and sentenced him to 15 months in prison. His supporters rioted, and more than seventy people died. Though he ultimately served only two months, the Constitutional Court ruled him ineligible to hold elective office when he attempted a parliamentary run in 2024.

Nonetheless, Zuma’s new party participation in the 2024 elections pushed the ANC below 50 percent for the first time, necessitating a coalition government. (Zuma claimed, without evidence, that the electoral commission had robbed his party of a two-thirds majority.) The ANC joined the center-right opposition in an uncomfortable relationship that gives South Africa its best chance since 1994 for meaningful, responsible change.

South Africa’s response to Zuma’s outrages wasn’t perfect. Its government has only implemented a few reforms to prevent another Zuma. Many ANC leaders who enabled his excesses remain in power. The culture of bad government he fostered—corruption and poor government performance—will be hard to root out.

But South Africa has done much better than the United States in confronting its autocrat. Our Zuma is back in power, and he’s likely to have even less shame and cause even more harm. Like Zuma, Trump aims to capture more of the machinery of government this time, targeting the same types of agencies and institutions as Zuma—intelligence, law enforcement, finance, media.

THERE ARE FIVE LESSONS Americans could learn from South Africa’s experience defending its democracy:

Corruption is not a victimless crime. The exploitation of the South African state cost ordinary South Africans dearly, kneecapping an already struggling economy and disrupting basic services. Zuma set the project of post-apartheid recovery back many years and undermined people’s trust in the government. This trust deficit may yet fuel a more radical, dangerous political movement in a country with a bloody history. In America, too, the toxic, high-stakes politics and corrupt, profligate economics of the Trump years mean we are further from solving our most vexing problems, like access to affordable healthcare and housing, the stability of our entitlements programs, racial justice and reconciliation, and immigration. These problems will compound with time, risking a more radical backlash.

Complacency can turn blessings into a curse. Compared to South Africa, the American economy is more resilient, and our institutions are more durable. But that’s a double-edged sword. Our good fortune has bred a complacency that a country like South Africa literally can’t afford. American voters, for example, are going to have electricity regardless of who is in power (well, maybe not if they live in Texas), and their economic hardship will pale in comparison to that of the average South African, who lives with 33 percent unemployment and one of the world’s highest crime rates. And unlike South Africa’s business community, which served as a check on Zuma, much of ours is bending the knee to Trump.

Do not obey in advance. Key figures in the Zuma story, most notably Pravin Gordhan, forced Zuma to absorb the full political consequences of his actions. As finance minister after Nene’s firing, he waged bureaucratic war against Zuma’s corruption and stared down threats by the National Prosecuting Authority to charge him with fabricated crimes. Sadly, it’s unthinkable at this point that Trump’s appointees will resist him even in private. But every American, from the protester who is unlawfully arrested to the pollster who is sued to the low-level bureaucrat who refuses to follow an unconscionable order, should only go kicking and screaming (within the bounds of the law). We should channel Gordhan, who fought for democracy first against apartheid, then against Zuma.

Go to court early and often. South Africa’s fiercely independent judiciary proved to be a firewall, not only protecting Zuma’s political opponents and interfering in his corrupt schemes, but also convicting him and—if only, America!—barring him from elective office. America’s courts have already been less of an obstacle for Trump, but they remain our best hope. Where federal charges aren’t pursued, perhaps Democratic state attorneys general and civil litigators can step up. And, yes, we will need armies of pro bono lawyers to defend those who refuse to go quietly.

Fully document the truth. South Africans frequently joke about their fondness for commissions, whose recommendations are often ignored. But starting with its vaunted Truth and Reconciliation Commission, which exhaustively assembled evidence of apartheid-era crimes in part by offering clemency to perpetrators willing to testify, South Africa has demonstrated the importance of fully reckoning with its sins. Enshrined in the constitution is the Office of the Public Protector, a permanent, independent investigatory authority to which the government is subject. The Zuma-era public protector, Thuli Madonsela, relentlessly gathered and exposed evidence of his abuses. President Ramaphosa stood up the Zondo Commission specifically to investigate and document state capture. Its work has inspired subsequent government action and aided the indictment of over 200 individuals, including two of the Gupta brothers. Americans still await a credible, comprehensive investigation of Trump’s corruption.

Compared to South Africa, the United States is falling behind. But so far—and it’s still too soon to tell—South Africa has shown it’s possible for democracy to weather an authoritarian hurricane. The United States has many more institutional and economic resources with which to clean up our storm damage. But first we need to get out of the storm.