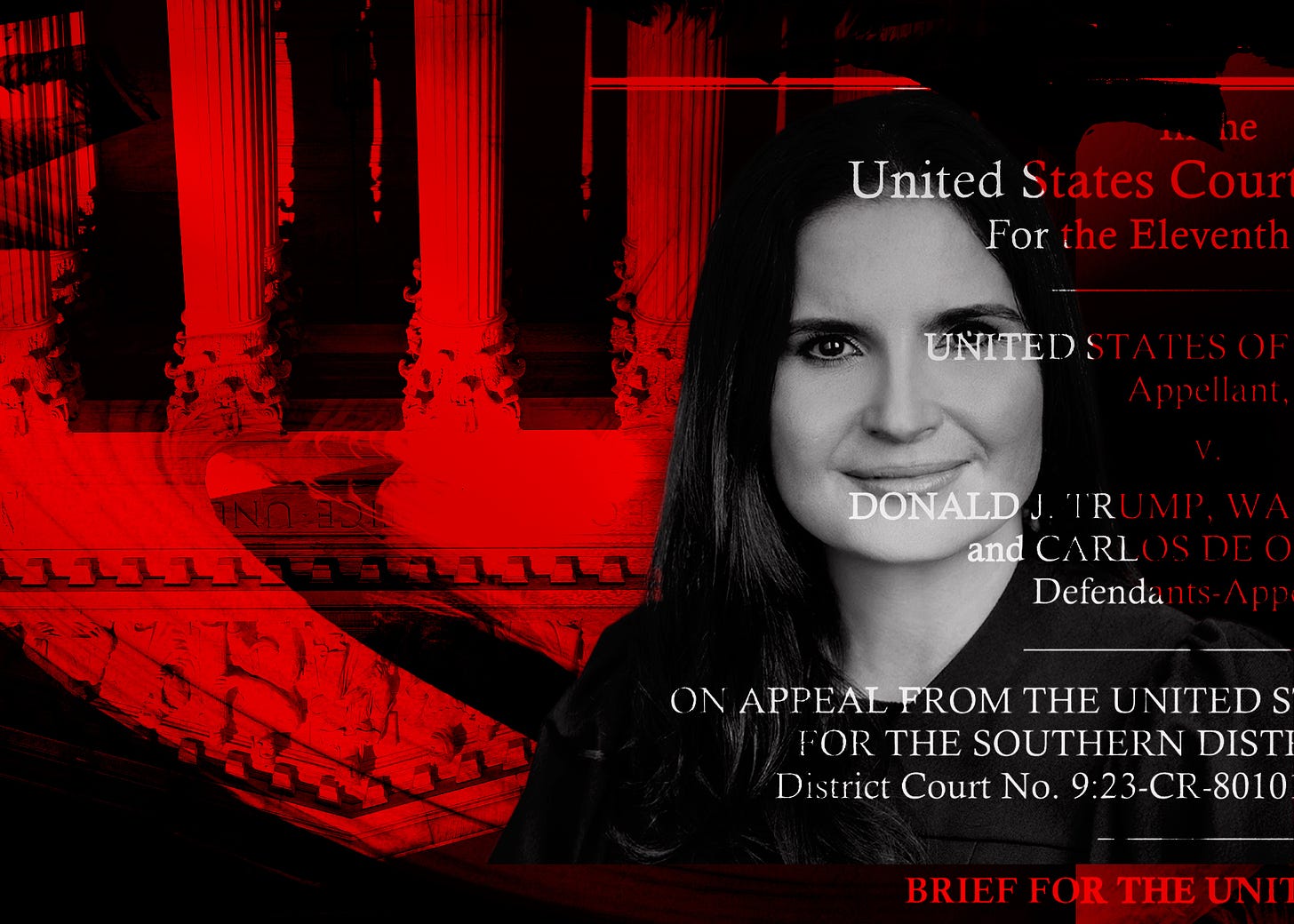

Jack Smith Ain’t Cannon Fodder

His appeal of Judge Cannon’s ruling killing the Mar-a-Lago case is powerful and persuasive—but will it be enough?

ON MONDAY, SPECIAL COUNSEL JACK SMITH filed an appeal of U.S. District Judge Aileen Cannon’s outright dismissal of the classified documents case filed against Donald Trump in Florida. That case was widely perceived as the strongest of the four criminal indictments against Trump (the others being the January 6th indictment filed in federal court in Washington, D.C., the election-fraud case filed in state court in Georgia, and the Manhattan hush money case that produced a criminal conviction on 34 charges in June). Last month, Cannon tossed out the indictment on foundational grounds, declaring Smith himself an unconstitutional actor, as if everything he touches is worthless as a matter of law. The appeal signals that the Justice Department is not going to tolerate Smith getting “fired” this way.

Cannon is a trial court judge, so her deeply flawed ruling has no weight beyond this particular case. Still, Smith’s filing the appeal carries a risk. The Supreme Court in Trump v. U.S. created immunity for crimes committed by presidents using their “official” power. In his concurring opinion in that case, Justice Clarence Thomas offered a roadmap for Cannon’s dismissal of the case on the grounds that Smith’s very office is unconstitutional.

The U.S. Court of Appeals for the Eleventh Circuit will probably reverse Cannon and rule that Smith’s special counsel appointment is lawful. But either way, that decision will be appealed to the Supreme Court, where it will find some justices friendly to Cannon and, more importantly, to Trump. Whether Thomas can muster four more votes to affirm Cannon’s sweeping conclusion remains to be seen, but if he does, the constitutional implications are significant.

In his appeal, Smith argues that the position of special counsel is supported by a host of laws that draw on the Congress’s Article II authority to create “inferior” officers. They include the following:

Congress made the attorney general the “head of the Department of Justice,” and Congress “vested” in the attorney general “all functions of other officers of the Department of Justice” (including prosecutions);

Congress empowered the attorney general to authorize “any other officer, employee, or agency of the Department of Justice” to perform any of those functions (such as U.S. attorneys and assistant U.S. attorneys);

Congress authorized the attorney general to hire attorneys who are “specially retained under authority of the Department of Justice” as “special assistant[s] to the Attorney General or special attorney[s]”;

Congress made clear that “any attorney specially appointed by the Attorney General under law, may, when specifically directed by the Attorney General, conduct any kind of legal proceeding, civil or criminal, . . . which United States attorneys are authorized by law to conduct”; and

Congress also provided that the attorney general “may appoint officials . . . to detect and prosecute crimes against the United States.”

Cannon nonetheless ruled that, despite these statutes, Merrick Garland had no legal power to appoint Special Counsel Jack Smith.

You don’t need to be a lawyer to appreciate what a stretch this is.

Worse (as if that were possible), there is already a Supreme Court case affirming that Congress, together with the attorney general, has the legal authority to appoint people like Jack Smith. In United States v. Nixon, the Supreme Court in 1974 unanimously held that the numerous statutes quoted above together “vested” in Congress and the attorney general “the power to appoint subordinate officers,” including the Watergate special prosecutor, and to “conduct criminal litigation of the United States Government.”

In the Nixon case, the Court cited the very same statutes that Smith now relies on to support his appointment. Although it’s true that Nixon didn’t present precisely the same facts and issues that Smith’s appointment does, Cannon didn’t wrestle with the Court’s logic at all. Cannon dismissed Nixon as nonbinding dicta—she simply brushed it all aside.

So this lower court federal judge basically chose to ignore Supreme Court precedent.

AN ESPECIALLY BIZARRE additional wrinkle: The prosecution of Hunter Biden was orchestrated by Special Counsel David Weiss, who under Cannon’s reasoning was also an unconstitutional actor. So if Justice Thomas gets his way, a ruling that Smith is unconstitutionally appointed would mean that Hunter Biden’s conviction should probably be thrown out, too. There are many other special counsels out there. A swipe at Smith also means their investigations could be on the chopping block. (Remember Special Counsel Robert Hur’s news-grabbing report that Joe Biden’s storing of classified information at his Delaware home did not justify criminal charges?)

President Joe Biden sits at the apex of the Department of Justice. Even though there is a practice of DOJ independence from the president, especially since Watergate, Biden could have exercised Trumpian bitterness and taken care of his own by calling off Hur’s probe altogether. Or he could have directed his Justice Department to let Cannon’s ruling stand while his son appeals his own conviction on the same grounds.

So far, unlike Trump, Hunter Biden’s lawyers haven’t complained to the federal judge in Delaware that his entire criminal case is constitutionally invalid. Meanwhile, his dad has stepped away from the Democratic nomination for president, ceding the most powerful seat in the land, for the sake of democracy. Hopefully, the other eight justices on the Supreme Court will side with reason and fidelity to the rule of law this round as well.