States Launch Massive Lawsuit Against Facebook and Instagram

They’re bypassing Section 230 by going after Meta’s mode of business rather than the specific content it hosts.

ON TUESDAY, OVER HALF of the states’ attorneys general (including Letitia James of New York, whose fraud case against former President Donald Trump and his businesses is now in its fourth week of trial) sued the social media giant Meta in federal court in California, claiming that its Instagram and Facebook platforms are deliberately addictive and harmful and that they “exploit and manipulate” children. The 233-page civil complaint is a monster of a filing, citing violations of the federal Children’s Online Privacy Protection Act (COPPA) and its implementing regulations, which prohibit “unfair or deceptive acts or practices” regarding the collection, use, or sharing of data relating to children under the age of 13. COPPA also requires online platforms to obtain prior verifiable parental consent before they collect or use their kids’ data.

The case also raises claims under dozens of states’ consumer protection laws banning unfair, deceptive, unconscionable, and misleading business practices. It seeks a permanent injunction stopping a slew of Meta’s social media practices, which the lawsuit claims deliberately prioritize profit over the well-being of a generation of hapless children, and unspecified money damages to be paid to the states.

WHAT’S INTERESTING ABOUT THE LAWSUIT is its potential parallels to tobacco litigation of the last century. When they began in the 1950s, the lawyers who sued the tobacco industry mostly failed because courts bought cigarette manufacturers’ claims that smokers were to blame for their own smoking. Judges also ruled that federal laws preempted state laws, effectively immunizing the companies from liability. It wasn’t until the late 1990s, when 46 states entered into a massive settlement of numerous lawsuits brought under consumer protection and antitrust laws, that tobacco litigation turned around. The settlement required four of the largest tobacco companies to refrain from certain advertising claims and pay billions to fund states’ health care costs and educate the public on smoking risks.

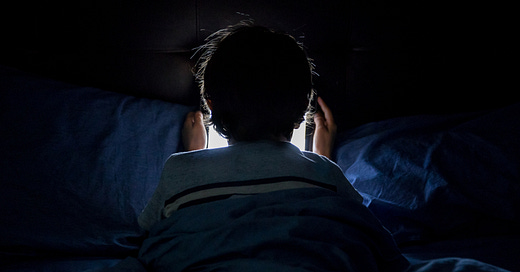

Thus far, the legal conversation over addressing the ills of social media has focused on Section 230 of the Communications Decency Act, in which Congress in 1996 granted online media companies broad immunity from lawsuits arising from the content posted on their platforms. The states’ lawsuit against Meta bypasses Section 230, relying instead on consumer protection laws in addition to COPPA to claim that Meta’s business model focuses on increasing children’s engagement with its platforms through data harvesting and targeted advertising, while falsely claiming that their social media platforms are safe and not designed to trigger compulsive and extended use. Meanwhile, the states argue, Meta’s concerted drive to popularize “Likes” has harmed children’s mental health, and visual filters promote eating disorders and body dysmorphia.

These kinds of critiques of Facebook, Instagram, and other social media platforms have been hotly debated for years among psychologists, social scientists, journalists, policymakers, educators, and parents. Last month, the Wall Street Journal published a story revealing that leaked documents indicate Meta had knowledge that Instagram is psychologically toxic for teen girls, despite the company’s contrary representations to the public. Interestingly, it was a leak of internal documents by an anonymous whistleblower in 1994 that made public how much Brown & Williamson Tobacco Corporation knew of tobacco’s addictive qualities, ultimately prompting the turn in litigation tactics and success. In 1996, the Justice Department filed racketeering and conspiracy claims against the big tobacco companies, claiming they lied to the American public, and won a judgment in 2006. From 1998 until 2021, cigarette use among adults plunged from 24 percent to 12 percent, with an even steeper drop among teens.

In a wash of otherwise grim news for America’s youth—from AI to climate to guns—the Meta lawsuit offers a glimmer of hope. If the company were forced to the negotiation table, it might hammer out changes to its business model that account for some of the risks of social media addiction to children and other users. All it would take is for the judge to issue an injunction on one—not all—of the many counts in the complaint to force Meta to take notice.

Until then, Meta’s cost-benefit analysis is likely to justify keeping its astronomical revenue stream untouched for as long as possible, even if it means paying expensive lawyers to stave off an injunction or settlement. In defense, Meta may point the blame at users for their own social media overuse, in addition to claiming that whatever harms children are experiencing today are not caused by their products—arguments that were presumably raised in one form or another by Big Tobacco.

What ultimately sank the tobacco industry’s defense were the lies. In April 1994, seven CEOs notoriously testified under oath to Congress that they believed nicotine was not addictive. Later, internal documents dating back to the 1950s made plain that the companies not only long knew that cigarettes were addictive, but also that cigarette smoke contained “ionizing alpha particles”—or radioactive matter—that lodged in the lungs of smokers, adding to the cancer risk.

In 2006, U.S. District Judge Gladys Kessler wrote in a 1,683-page opinion that the tobacco companies “have marketed and sold their lethal products with zeal, with deception, with a single-minded focus on their financial success, and without regard for the human tragedy or social costs that success exacted.” Social media companies like Meta have their own single-minded focus on their financial success; we’ll see whether this massive lawsuit by state AGs might bring them to care about the human and social costs of their products.