Steve Bannon and MAGA Martyrdom

A practitioner of Leninist tactics, he can be expected to make the most of the contempt of Congress charges he faces.

On Monday, Stephen K. Bannon surrendered to federal authorities and was released on his own recognizance after a court appearance in the afternoon. He was not reticent. To the contrary: He brought along his own people to livestream and record an impromptu street-side appearance as he left the court building. Those who saw it on the TV news channels noted his excitement, his ability to seize the moment to gain more support from the MAGA movement, and to extol his goals. “We’re taking down the Biden regime,” he announced.

Bannon went on to tell the crowd—made up both of his supporters and some anti-Bannon protesters—that

this is going to be the misdemeanor from hell for Merrick Garland, Nancy Pelosi, and Joe Biden. Joe Biden ordered Merrick Garland to prosecute me from the White House lawn when he got off Marine One. And we’re going to do—we’re going to go on the offense, we’re tired of playing defense, we’re going to go on the offense on this. And stand by.

Claiming that his indictment on two charges of contempt of Congress violated “freedom of speech and liberty,” he pledged that he was “never going to back down. They took on the wrong guy this time, okay?’ As he turned away he had one more comment: “If the administrative state wants to take me on, bring it. Because we’re here to fight this . . . we’re going to go on the offense.”

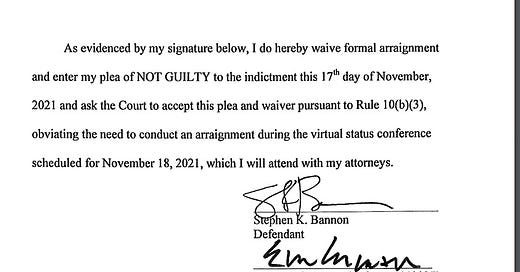

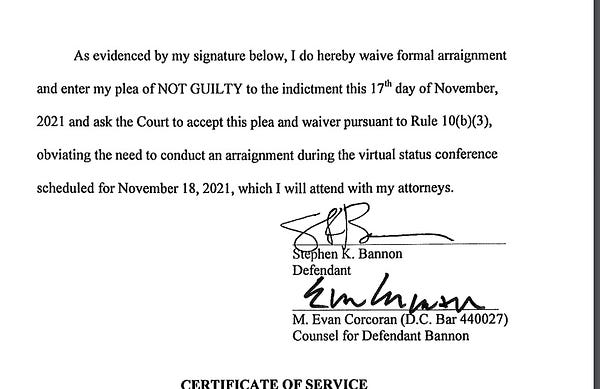

Bannon clearly saw the opportunity to gain attention and to let his audience know that he would continue as he has—and would not cooperate with the House committee investigating the January 6th insurrection. He was scheduled to appear this morning before a federal judge (virtually) for his arraignment, but yesterday filed a motion waiving the arraignment and pleading not guilty:

In his Washington Post column, Michael Gerson notes this week that many public figures in the GOP and Trumpist movement are dangerously contemplating violence. They seek, he writes, to unleash “the force of nihilism in American politics—the mad desire to blow up our political order and put citizens at one another’s throats.” That description certainly applies to Steve Bannon.

Bannon spelled out his plans and strategy to me way back on November 12, 2013, at a book party held at his D.C. townhouse (the so-called “Breitbart Embassy”). “I’m a Leninist,” he told me as he introduced himself. He then went on, as I recounted in a 2016 Daily Beast article, to inform me that “Lenin wanted to destroy the state, and that’s my goal too. I want to bring everything crashing down, and destroy all of today’s establishment.” The “establishment” included the GOP leaders and what others considered the conservative press. National Review and the Weekly Standard were, in Bannon’s eyes, “left-wing magazines.” I ended my article with a prediction that, sadly, has proven correct. I wrote that should Bannon succeed, there would be “a hostile takeover of the GOP.”

In attempting to create his revolutionary movement for a kind of populist nationalism, Bannon took ideas from both the left and the right. His claim to populism extended to praising Bernie Sanders’s call for limiting immigration because he thought it hurt American workers. In a 2018 interview with Ben Schreckinger of GQ magazine, Bannon proclaimed that “the greatest power on earth is the working men and women in this country,” which might as well have come from Eugene V. Debs in the 1920s. Schreckinger responded that Bannon’s words reminded him of Woody Guthrie. Bannon responded that although “the populist left” had taken Guthrie’s most famous song as their own anthem, “This Land is Your Land,” is “still one of the most powerful songs written in this country. So I’m a big fan.” Were he living, Guthrie, a self-proclaimed Communist and Marxist, would have been horrified.

Above all, Bannon’s Leninist tactics led him to take the strategy for his populist campaign from the most extreme leftists in the 1960s: the Weathermen, later the Weather Underground. He echoed particularly the New Left’s most visible and potent leader, Tom Hayden. As David Frum noted in the Atlantic, Bannon’s antics are reminiscent of the Chicago Seven, the defendants (including Hayden) in the 1969-70 trial recently glamorized in Aaron Sorkin’s Netflix movie. In that trial, the defense ignored the law and normal courtroom procedures to stage what Frum calls a “media spectacle intended to show total contempt for the rules, and to propagandize the viewing public into sharing their contempt.”

The basis of the charges against the Chicago Seven was the violent mayhem during the 1968 Democratic convention. Hayden instigated those who came to protest to engage in violence. Frum rightly sees a point of comparison here between Hayden and Bannon. Hayden thought that if the 1968 protesters turned violent, it would provoke a tough response from the mayor and the Chicago police, thereby exposing the true “fascist” nature of the United States. Bannon, meanwhile, anticipated an “attack” and “all hell” breaking loose on January 6—and indeed, the pro-Donald Trump mob, as Frum writes, “forc[ed] a police officer to shoot to defend the officeholders whom it was his duty to protect.”

Not only did Bannon adopt the tactics of Hayden, but he has also paid homage to the Weathermen. In a Tea Party speech in New York City on April 15, 2010, Bannon inflamed the rowdy crowd, beginning with a fierce attack on the “financial elites in the political class” who during George W. Bush’s and Barack Obama’s administrations arranged bailouts and other economic rescue measures to prevent a major financial crash after the collapse of Lehman Brothers.

Then, Bannon made a statement that echoes a line the late democratic socialist leader Michael Harrington used to make in his speeches; Harrington said that America creates “socialism for the rich and capitalism for the poor.” In Bannon’s rendering, the American system offers “socialism for the very poor and the wealthy, and a brutal form of capitalism for everybody else.”

Next, Bannon made a statement using the exact words and rhetoric spoken by the Weathermen—the terrorist branch that emerged from the New Left, known most for planting bombs at police stations, banks, large corporations, and the U.S. Capitol. They were so proud of this that in their own publication, they proudly listed all the targets at which they had successfully planted and set off bombs. Infamously, on March 6, 1970, some Weathermen were making bombs in a Greenwich Village townhouse when they inadvertently exploded the bombs, causing the death of three of their own and the injury of the others present. Had they not blown themselves up, the bombs would have been used at a dance for new Army recruits at Fort Dix in New Jersey. Hundreds might have been killed or maimed. Bill Ayers, perhaps the most well-known of the group’s alumni, wrote that “We who survived went on to carry out a handful of highly visible antigovernment bombings.”

Bannon ended his 2010 speech with a reference to the left-wing terrorists lifted from Bob Dylan’s “Subterranean Homesick Blues”—“It doesn’t take a weather man to tell you which way the wind blows”—and then an even more explicit, if somewhat obscure reference, to the Weathermen: “The winds blowing off the high plains of this country, through the prairie, and lighting a fire that’s gonna burn all the way to Washington in November.” Although his audience may not have gotten the reference, Bannon was saying that he and the Tea Party were revolutionaries, a new right-wing version of the Weather Underground, who also want to bring down the system. The publication in which the Weather Underground spread its ideas was named Prairie Fire because, they wrote, “a single spark can start a prairie fire.”

Bannon most likely agrees with the Weathermen’s Leninist strategy, as delineated on page 143 of Prairie Fire:

A movement has no right to exist if it doesn’t fight. The system needs to be overthrown. . . . Revolutionary movements must be contending for power, planning how to contend for power, or recovering from setbacks in contending for power. Certainly every movement must learn to fight correctly, sometimes retreating, sometimes advancing. But fighting the enemy must be its reason for being. We build a fighting movement.

In another speech from that period, delivered in Florida in October 2011, Bannon sounded like Bernie Sanders. He branded recent high-school grads “generation zero” because their parents’ generation passed on to them “zero net worth.” Middle-class people who sent their children to college were, according to Bannon, “paying for their own and their children’s destruction.”

Bannon then attacked the bankers of Goldman-Sachs—where, ironically, he made his own early fortune—for getting rich over the backs of regular people who lost their homes and saw their incomes regularly declining. “There’s no recession in the Hamptons,” he said. “There’s no recession in Georgetown.” Bannon’s fans, who would become MAGA mainstays, were “the last line of defense” protecting the United States of America.

One must wonder if Bannon’s listeners even knew that the wealthy business and banking leaders that he condemned were the very people among whom Bannon lives, and from whom he was made rich from investments in their companies, and is most comfortable with. Remember, this is the guy who was arrested on fraud charges while staying on the yacht of a Chinese émigré billionaire. That 2020 arrest was for allegedly defrauding the people he asked to give money to a help underwrite construction of the wall on Mexico’s border. Bannon reportedly siphoned off over a million dollars from the group for himself. But of course President Trump, on his last full day in office, pardoned Bannon. So much for the “middle-class people” Bannon professed to care about.

Does Bannon consider himself today’s Tom Hayden, but from the right? Hayden, said the social-democrat Irving Howe, “was auditioning to become the American Lenin.” The left-wing journalist Jack Newfield thought that Hayden “would become the first American president to emerge from the ranks of the New Left.” Hayden tried to be each but failed to be either.

When he died two weeks before the 2016 election, Hayden’s obituaries discussed his career as a leftist moderate Democrat who entered politics in California but who couldn’t move beyond the state assembly and state senate to statewide or national office. But before he turned to electoral politics in the mid-1970s, extolling Robert F. Kennedy as his model and hero, he was an extremist ideologue. He lived in a far-leftist Berkeley commune, bought guns, and engaged in rifle practice in the hills with his cadre, preparing for the coming revolution he thought would be led by the Black Panther Party and by young people in the “liberated zones” of Berkeley and of New York City’s Upper West Side.

If one views Bannon as a new right-wing version of Tom Hayden, or if he views himself that way, perhaps he too will choose to run for office. Or he might prefer to remain a strategist for other politicians, especially if Trump decides to run again, at which point Bannon may again seek an appointment from which he could again try to steer Trump in the direction he favors.

Bannon made clear on Wednesday that he intends to fight the contempt of Congress charges against him. If he can find a way to draw out the court proceedings and to turn them into circus, you can expect him to do that. If he is found guilty, he could face up to a year in prison and a $100,000 fine for each charge of contempt. That’s a small amount to Bannon, given his wealth—but don’t be surprised if he sets up a legal defense fund to raise money off his followers. Imprisonment would make Bannon a martyr for MAGA, and could strengthen his standing to become the movement’s titular leader after Trump.

Of course, he also has the option of submitting to the subpoena and appearing before the House January 6th Committee. If Bannon does appear, instead of invoking the claim of executive privilege he could assert a Fifth Amendment privilege. Back in the 1950s, when gangsters and Communists who were called before congressional committees “took the Fifth,” the public at large considered it an admission of guilt. Likewise, most Americans today—minus the Trumpist base—would view Bannon’s taking the Fifth as a tacit admission of guilt. (Congress, for its part, could reject a Fifth Amendment assertion and pursue a new contempt charge, or could seek an immunity order that would compel testimony.)

One other possibility: Bannon could appear before the committee and do what Abbie Hoffman and Jerry Rubin did during the Chicago Seven trial when they made a fool of Judge Julius Hoffman by engaging in crazy antics. He could stage a performance and try to ridicule and undermine the entire purpose of the investigation, seeking to embarrass and ridicule Adam Schiff, Liz Cheney, and the other committee members.

If Bannon is sent to prison, he will presumably, if permitted, give prison interviews to all who request them: Fox News and OAN and Newsmax, talk-radio shows and right-wing podcasts, and of course the Trumpist websites like American Greatness, Breitbart News, and Frontpagemag.com, the publication of the David Horowitz Freedom Center, which in 2017 gave Bannon an award for “courage.” A committed Leninist fighter knows never to give up on the dream of revolution.