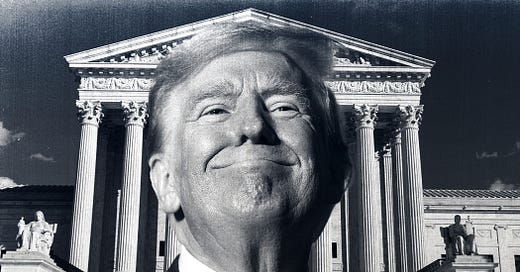

Supreme Court Poised to Transform the Presidency, Empower Trump if Re-Elected

Based on oral argument in the presidential immunity case, the Court’s conservative justices seem prepared to effectively reward Trump for January 6th.

ON THURSDAY, THE SUPREME COURT heard oral argument on Donald J. Trump’s extraordinary bid for absolute, unqualified immunity for crimes committed by presidents in office. Unsurprisingly, even the Court’s right-wing justices weren’t interested in completely immunizing presidents from criminal liability for any and all crimes committed while president. That was never in serious contention. Judging by their questions, however, what the conservatives are evidently willing to do is manufacture some form of criminal immunity that will be governed by a private-versus-official conduct standard (with only official conduct protected), and then send the case back to District Judge Tanya Chutkan to parse Special Counsel Jack Smith’s January 6th indictment of Trump and excise the parts for which Trump would be protected under the Court’s newly minted criminal immunity test. How the Court will draw the line between official and private conduct is anyone’s guess, particularly if presidents abuse official powers for purely personal gain.

That would be a win for the insurrectionist-in-chief.

A refresher on the background law: Unlike members of Congress, who have immunity for legislative acts under the Constitution’s Speech and Debate Clause, presidents get no explicit immunity in the text of the Constitution. Nonetheless, in a 1982 ruling, the Supreme Court granted presidents immunity from civil liability on the theory that otherwise, they’d be inundated with lawsuits for money damages by unhappy Americans just for doing their job. Under the civil immunity doctrine, the question boils down to whether a given action is within the president’s official job description or is private. That distinction is why the Court allowed a sexual harassment lawsuit to proceed against President Bill Clinton while he was a sitting president—the conduct occurred before he was president, so the lawsuit was fair game.

The question of criminal immunity for presidents has never been an issue—until Trump. Richard Nixon left office short of being impeached over Watergate and his successor, Gerald Ford, pardoned him for any possible crimes that he might have been prosecuted for, on the presumptive understanding that he could have been prosecuted but for the pardon. The text of the Constitution also envisions criminal liability for former presidents, expressly stating that “the Party convicted [of impeachment] shall nevertheless be liable and subject to Indictment, Trial, Judgment and Punishment, according to Law.” Yet that language didn’t come up during oral argument, and it certainly didn’t stop the Court’s so-called “textualists” from signaling their openness to criminal immunity for presidents in at least some circumstances.

The Court of Appeals for the D.C. Circuit, which heard the case before the Supreme Court, had no reservations about declaring that Trump had no immunity whatsoever from the charges he faces over January 6th. Michael Dreeban, the former deputy solicitor general who argued the case for Special Counsel Jack Smith, nonetheless came prepared to make some concessions—and concessions he made. He allowed that there are certain presidential actions within the express terms of Article II of the Constitution—such as exercising the powers to pardon, to receive foreign ambassadors, to veto legislation, and to make appointments—that would be immunized from any civil or criminal liability. If Congress were to pass a law constraining those powers or criminalizing certain kinds of presidential acts within those powers, in other words, such a law would be struck down as unconstitutional. That middle ground will encourage the justices to depart from the lower court’s ruling that the January 6th indictment is not categorically unconstitutional.

But whether Congress could pass a law that impinges on core presidential authority is a very different question from whether the president is subject to indictment under existing criminal laws that govern everybody else.

Anything but the narrowest immunity doctrine would mean far broader protections for future presidents seeking to dodge accountability for bad deeds. Depending on how the Court writes its opinion—and how far future presidents, White House counsels, attorneys general, and Department of Justice lawyers are willing to stretch their words—large swaths of presidential action that were unimaginable before Trump could become not just real but protected.

The problem with giving such a protection to all future presidents comes down to incentives. Criminal laws exist to deter bad conduct. And ironically, it’s bad conduct—trying to steal an election and stoking violence to disrupt the peaceful transfer of power—that in this moment is giving the Supreme Court occasion to enhance the power of presidents to do that kind of thing with even greater impunity.

And here’s a further disturbing thought, suggested by Dreeban’s hedging: If Trump wins in November, he will go after Biden criminally, so maybe the kind of presidential immunity being debated by the Court today is needed to protect against the virulent political prosecutions that Trump has promised will immediately follow his inauguration.

For now, with only one of his four criminal cases likely moving forward before voters head to the polls, the Supreme Court seems to have handed Trump another decided win. Tragically, that win is not just for Trump—whose January 6th trial will be delayed as his legal team slices and dices the indictment and appeals Chutkan’s rulings on which parts can move forward—but also for the dark forces that threaten to convert our system of government from a democratic republic ruled by the people into one in which unconstrained power could be lodged in a single, despotic man.