Taking Reparations Seriously

Understanding what the conversation about reparations is, and isn't, about.

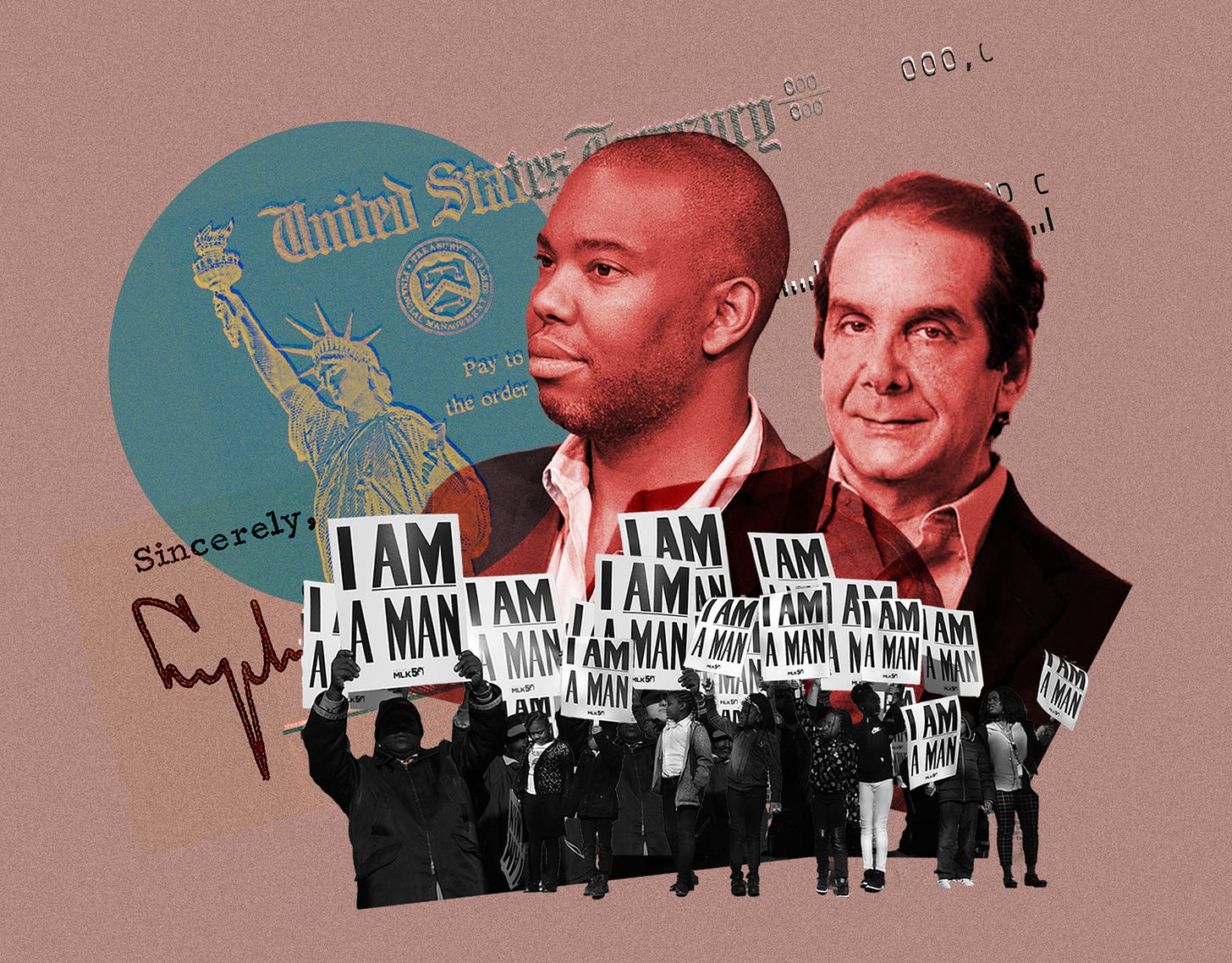

In 2014, Ta-Nehisi Coates wrote his seminal essay "The Case For Reparations." Five years later we are talking about reparations again. This presents a fresh opportunity for Americans at large—liberals, conservatives and everyone of goodwill—to thoughtfully consider the ways in which systemic racial injustice has warped our social fabric.

For the stark reality is that America’s grappling with race is far from done. As the distinguished conservative commentator Charles Krauthammer wrote: "The African-American case is unique. There is nothing to compare with centuries of state-sponsored slavery followed by a century of state sponsored discrimination." Contemporary Americans, he asserted, were still bound by this dynamic: “Even when guiltless we remain collectively responsible for our nation's past."

This conclusion links Krauthammer to Coates. The issue of reparations, Coates hoped, could drive a "national reckoning that would lead to spiritual renewal."

A vehicle is at hand. Senator Cory Booker and Representative Sheila Jackson Lee have now called for a commission on reparations to, as Booker puts it, "bring together the best minds to study the issue and propose solutions that will finally begin to right the economic scales of past times."

The danger is that rigorous discussion will be subsumed by political opportunism. Among Democrats, Booker worries it could become "just a box to check on a presidential list." And it takes little imagination to picture Donald Trump using a conversation about reparations to further metastasize white identity politics.

The subject is already fraught. Polling shows reparations to be a wedge issue which creates multiple fractures: between blacks and whites; Democrats and Republicans; young and old.

But one figure stands out: roughly 80 percent of whites oppose "reparations" as they understand it. This is political catnip for those bent on exploiting our divisions. Says GOP strategist Whit Ayres: "[T]he idea that you resolve those issues by taking money from white people and giving it to black people will make race relations worse, not better. Republicans would love to have that debate."

But this isn’t—or shouldn’t be—about Republicans, Democrats, or the 2020 election. For the subject of reparations, and the need for Americans to understand it, transcends politics. It’s about how the racial past affects our present and future, and what to do about that.

Two-hundred and fifty years of slavery was only the beginning. But it requires fresh scrutiny today.

Setting aside Native Americans, African-Americans were America’s only draftees. Other immigrants came to America seeking a better life. African-Americans were brought here in chains to be systematically dehumanized as involuntary engines of the white economy. As Coates writes, "by 1840, cotton produced by slave labor constituted 59 percent of the country's exports." He further quotes the historian David Blight: "'Slaves were the single largest, by far, financial asset of property in the entire American economy.'"

For descendants of other immigrant groups who ask why, in their view, African-Americans "aren't more like us" the answer is simple. They never were, because America never let them.

As voluntary Americans, other immigrant groups freely formed families which coalesced into communities of kind wherein newcomers found welcome and advancement. By contrast, Coates notes that "25 percent of interstate [slave] trades destroyed a first marriage and half of them destroyed a nuclear family . . . Here we find the roots of American wealth and democracy—in the for-profit destruction of the most important asset available to any people, the family. The destruction was not incidental to America's rise; it facilitated that rise."

The essence of slavery was the comprehensive eradication of human hope and potential. That this devastating denial of humanity—enforced by law and reinforced by fear and cruelty—continued for two and a half centuries defies easy reckoning in the present.

Yet slavery is the part of our racial history that most of us think we understand. Far fewer truly comprehend the depth of enslavement—political, legal and economic—which followed the formal end of slavery. Effectively, the South imposed a relentless apartheid on the great majority of America's blacks by fusing terror and violence with a race-based legal regime.

Much of this history informs Douglas Blackmon's Slavery by Another Name: The Re-Enslavement of Black Americans from the Civil War to World War II. Though the subtitle is apt, its end date seems at least two decades too soon. Twelve years after the Civil War, the last gasp of Reconstruction was replaced by "industrial slavery"—laws designed to jail blacks for petty offenses as a predicate for the state leasing them out as convict laborers. Other blacks were subjected to peonage wherein farmers, deemed to be perpetually indebted by white landlords, were extorted without recourse.

White governments systematically stole from blacks the rudiments of citizenship: the right to vote, hold property, or receive an adequate education - often literacy itself. Those who betrayed resentment—and many who did not—were subjected to lynching or beatings.

Cynical politicians used racism to eradicate the prospect of a shared economic sympathy between poorer whites and blacks—a tactic which resonates in America's present. Through the decision in Plessy v. Ferguson (1886), upholding segregation, the Supreme Court imbued racism with the majesty of constitutional law. Fleeing southern bigotry in search of legal protection, millions of blacks undertook "the great migration" north—where more legalized bigotry awaited.

To be sure, public policy too often reflected private prejudice which pervaded popular entertainment—the portrayal of blacks as a shiftless amalgam of predators and clowns. In film, DW Griffith’s The Birth of a Nation was particularly overt. But the more fondly remembered Gone With The Wind romanticize slavery and justifies racism as paternalistic and even benign.

Nonetheless, a principal driver of comprehensive racial disparity was America's federal government. In the military, white ethnic groups commingled; blacks were segregated. To gain southern support for the New Deal, Franklin Roosevelt countenanced discrimination against blacks nationwide. Writes Coates: "Old-age insurance (Social Security proper) and unemployment insurance excluded farmworkers and domestics—jobs heavily occupied by Blacks. When President Roosevelt signed Social Security into law in 1935, 65 percent of African-Americans nationally and between 70 and 80 percent in the South were ineligible."

In the North, federal policies systematically deprived African-Americans of the principal component of wealth creation: homeownership. This regime is exhaustively recounted in Richard Rothstein's The Color of Law: A Forgotten History of How Our Government Segregated America.

Discriminatory federal lending practices left blacks at the mercy of predatory lenders, who sold homes at inflated prices and then evicted families unable to pay their mortgages. The principal component was redlining: Federal Housing Administration maps which demarcated neighborhoods principally occupied by African-Americans as undesirable, which made it somewhere between difficult and impossible for blacks to obtain conventional, federally-backed mortgages.

Inevitably, the federal practice spread to the private mortgage industry, condemning blacks to neighborhoods where properly values deteriorated apace. This was reinforced by the federal Home Owners Loan Corporation, which insisted that any property it insured be covered by restrictive covenants forbidding the sale of the property to non--whites. These policies assured that millions of dollars in federal money flowed into segregated white neighborhoods.

Concurrently, liberal federal lending practices enabled whites to decamp for newly created suburbs which were racially pristine. As Rothstein writes, "the FHA suburbanized the entire nation on the whites-only basis.” When, in 1968, Lyndon Johnson established a commission to probe the roots of black unrest, it reported: "What white Americans have never fully understood—but what the Negro can never forget—is that white society is deeply implicated in the ghetto. White institutions created it, white institutions maintain it and white society condones it."

Fifty-one years later, most of these discriminatory federal practices are gone. But their legacy is governmentally-created deserts of opportunity. Three out of four neighborhoods redlined 80 years ago continue to struggle economically today. And in the meanwhile, the ongoing inequities in lending have allowed upper income white gentrifiers to replace lower income blacks in the urban neighborhoods that are changing - effectively reorganizing segregation..

None of the 100 cities with the largest black populations has a black homeownership rate close to that of whites. The Pew Research Center estimates that white households are worth roughly 20 times as much as black households. Only 15 percent of whites have zero or negative wealth; more than one third of blacks do. Because the marketers of subprime loans disproportionately targeted blacks, the 2008 financial crisis wiped out 53 percent of African-American wealth.

The cumulative impact in the present is devastating. The median wealth of white households is $171,000. Among black households it is $17,000. As Coates writes: "Effectively, the black family in America is working without a safety net. When financial calamity strikes—a medical emergency, divorce, job loss—the fall is precipitous.

Similarly, the racial earnings gap has returned to 1950s levels. Even black men with a Masters' degree earn $27,000 less than white men with the same credentials. And so this wealth gap is widening.

The legacy of federally-funded segregation still pervades the communities it helped create. Black children are more likely to grow up in poor neighborhoods than they were 50 years ago. Our schools are more segregated; those which are predominantly black have a higher concentration of kids in poverty. As the head of an education-advocacy group notes, "the re-segregation of education is a nationwide phenomenon, because of where people can afford to live and the connection between income and race."

Persistent, too, are health disparities. Infant mortality is more than twice as high among blacks as whites; three times more black women die giving birth. Compared to whites, blacks die younger; live fewer years free from illness; and develop chronic disease a decade earlier.

Because of residential segregation and substandard education, blacks have lesser access to jobs. They are more subject to discriminatory law enforcement.

These inequities do not exist in silos. They are inexorably intertwined. All too often, race still means destiny.

In short, black poverty is not white poverty's cousin. And because it is so highly concentrated, to many whites it becomes virtually invisible. All too often black America is a place white America zips past on the highway. It becomes too easy to talk about black "pathology" while ignoring the racial pathology which is embedded in American life.

This mistake is perhaps, our gravest and most persistent societal failure. In 1903, W.E.B. DuBois predicted that the great issue of the new century would be "the problem of the color line." At mid-century, Gunnar Myrdal worried that racial injustice threatened the success of American democracy itself. And 70 years after that, many of the root problems are still unresolved.

The civil rights movement of the 1960s was a remarkable achievement, ending official segregation, extending the ideal of equal opportunity under the law, enabling Southern blacks to vote, and accelerating the emergence of a growing black middle-class. But it was viewed as an end-point when it should have been seen as a beginning. And in the time between then and now, while African-Americans have made important gains in some areas, in other areas matters are actually worse.

For that matter, there is still far too little shared understanding. 20 years ago, the African-American economist Glenn Loury deplored the "widening rift between blacks and whites who are not poor—a conflict of visions about the continuing importance of race in American life."

Added Loury, "while it may be true that the most debilitating impediments to advancement among the underclass derive from patterns of behavior that are self-limiting, is also true that our history dealt poor blacks a very bad hand. Yes, there must be change in these behaviors if progress is to be made. But a commitment of support also be required from the broader society to help these folks help themselves."

For many , it may be uncomfortable to contemplate that whites have benefited, and millions of blacks continue to suffer, from a terrible flaw in our democracy. So it becomes congenial to convert a truism—that challenged communities must strive to lift themselves—into an excuse for ignoring our societal responsibility to help. But as sociologist Douglas Massey writes, "papering over the issue of race makes for bad social theory, bad research, and bad public policy."

Nonetheless such denial has a stubborn persistence. In 1891, the Chicago Tribune declaimed of reparations to African-Americans: "They have been taught to labor. They have been taught Christian civilization, and to speak the noble English language instead of some African gibberish. The account is square with the ex-slaves." One-hundred and twenty-eight years later—segregation, lynchings, peonage, redlining, and all the persistent suffocations of education, opportunity and human dignity having intervened—Mark Steyn told Fox News: "Slavery was abolished a century and 1/2 ago. Nobody alive today has a grandparent who is a slave. . . . I think you reach a point where we need to move on. The reparations thing, eventually, as the decades go by, becomes ridiculous.”

Part of the reason the healing of our racial wounds ceased, at the policy level, was because race became politicized along party lines. It began with a backlash against the civil rights laws of the 1960s which propelled a mass migration of Southern whites to the Republican party. This migration changed the GOP from what had been the party of Lincoln to a party that profited from white antagonism toward what, in the most charitable telling, they saw as the Democrats' over-concern with racial justice. However one assesses the substance of these arguments, or what drove them, the simple fact that our political divide became racialized had highly negative consequences for disadvantaged blacks.

Consider affirmative action—ground zero for our attempt to wrestle with race, through policy and law, for the last two generations.

To a remarkable degree, the opponents of affirmative action have persuaded millions of Americans that the principal racial injustice in today's America is discrimination against whites on behalf of blacks. In this view, the civil rights laws passed 55 years ago squared America's accounts - because the remaining problems faced by black Americans largely reflect their own deficiencies of culture and character, a truly just America must now be "race-blind." Moreover, they argue, affirmative action is not only unfair to whites but demeaning to successful blacks, casting doubt on their achievements.

Here’s Loury:

Affirmative action, however prudently employed, can never be anything more than a marginal instrument for addressing the nation's unfinished racial business. But the proponents of colorblind policy who bill their crusade against “preferences” as the Second Coming of the civil rights movement display a ludicrous sense of misplaced priorities. They make a totem of ignoring race, even as the social isolation of the urban black poor reveals how important “color” continues to be in American society. Argument about the legality of the government's use of race only scratches the surface, because it fails to deal with the manifest significance of race in the private lives of Americans, black and white.

Yet this counter-narrative has succeeded in blunting—and in some cases, reversing—laws and policies passed to protect minority voting rights and redress racial disadvantage, often under the color of constitutional law. In important particulars, the thought leader of the movement against affirmative action is a man of great ability and intelligence who, for many Americans, epitomizes judicial probity—Chief Justice John Roberts.

With respect to issues regarding race, for almost four decades Roberts has led the legal counterrevolution. Hence his famous dictum: "The way to stop discrimination on the basis of race is to stop discriminating on the basis of race."

This tidy formulation deserves fresh scrutiny, lest it be taken too far. It is hardly a universal prescription for resolving racial problems as they actually exist—the excessive and often deadly use of force against blacks; drug laws which punish blacks more harshly than whites; the stubborn health, housing, educational and economic inequities between the races.

It does not address the problem of voter ID laws which—despite the demonstrable absence of in-person voter fraud—plainly operate to suppress minority voting, an eerie echo of Jim Crow. This is hardly academic: such practices arguably deprived Stacey Abrams of the chance to become Georgia’s first African-American governor. One thinks of the great Southern novelist William Faulkner, who wrote: “The past is never dead. It’s not even past.”

Nor, critically, does Roberts’ legal epigram account for the dramatic and continuing differences in the circumstances of blacks and whites. Like many leaders of my generation, Roberts is the fortunate son of a prosperous family, gifted with a path to success which affords more opportunity for advancement than impetus for reflection.

But it should not take much thought to acknowledge that by accident of birth people like me—and John Roberts—are the beneficiaries of what is, effectively, the most successful affirmative action program in human history. We are white males born to educated and financially secure parents at the height of the American century. One need not be "woke" to be aware.

That's not guilt—it's simply fact. Compared to the great majority of African-Americans, John Roberts and I were born on America’s third base, free to use our talents and hard work to reach home. It is foolish to imagine that society can ameliorate every consequence of circumstance; unavoidably, some people will always have advantages over others. But it is worse than foolish to deny that the social and racial inequities which favored us persist today—or to imagine that “race-blindness” provides a sufficient response.

The case for doing better is practical and moral, and transcends ideology. As long as the legacy of racial discrimination persists, we are squandering human potential—economic and social—to America’s collective loss.

In the meanwhile, our racial divisions continue to harden along partisan lines.

A October 2017 study by Pew describes today’s political and racial chasm. Its findings were not all bleak: overall, 57 percent of Americans say that a major problem in addressing race is that people don't see discrimination where it truly exists; only 39 percent say the bigger problem is people perceiving discrimination which does not exist.

But beneath this hopeful number lies a stark divide: 84 percent of black people believe that most Americans don't see the discrimination which actually exists; 79 percent of Democrats agree. In contrast, 63 percent of Republicans say that the real problem is people imagining discrimination where there is none. Sixty-four percent of Democrats say that racial discrimination is the principal reason African-American struggle to get ahead, whereas 75 percent of Republicans believe that blacks are principally responsible for their own condition. Among Republicans, 59 percent believe that our country has already made the changes necessary to give blacks equal rights; 81 percent of Democrats believe there is more to do.

Which is as good a place as any to start the policy discussion on reparations.

Properly understood, reparations should not be viewed as recompense for slavery, but for four centuries of racial damage that still manifests itself across American society. Nor should it be reduced to parsing formulae for cash grants.

If the idea behind reparations is to truly comprehend our racial complexity -- and to make things better in ways which are truly meaningful- it must include a probing search for systemic answers, beginning with an effort to deepen our communal understanding. The task is daunting. As Coates says: "The idea of reparations is frightening not simply because we might lack the ability to pay. . . . [It] threatens something much deeper—America's heritage, history, and standing in the world."

This reckoning cannot be confined to liberals, or whites, or blacks, or a single political party. In order for the work to mean anything, it has to include all of us. We have to start by understanding that there will be no tidy solutions. But the fact that we cannot heal everything is no reason to do nothing.

That means grappling with issues of diabolical complexity. Among them are scope—as one example, Elizabeth Warren proposes that the discussion include Native Americans, who have their own distinctive history of systemic repression. She’s correct on the merits - this, too, is one of America’s foundational sins. But can Native Americans simply be rolled into a discussion of the specific legal and societal treatment of blacks? If not, what then?

Then there is the basic question of what “reparations” should even mean.

To many Americans, the term “reparations” suggests cash payments to the descendants of slaves. Less frequently, it is taken as specific government programs meant to strengthen communities of color. In sorting out this question, it is useful to contemplate Charles Krauthammer's advocacy of cash grants:

[America] can make both a symbolic gesture and a real one by giving, say, every African-American family a substantial sum in the tens of thousands. . . . Expensive, yes. But far less expensive than the corrosive, corrupt and corrupting alternative of affirmative action. . . .

In one grand gesture, acknowledgment is made not of collective guilt of collective responsibility. Reparations are paid. We then end the affirmative action experiment that has been disastrous both for African-Americans and for America as a whole. And we return to the original vision of Martin Luther King Jr. and the civil rights movement: color blindness. Krauthammer’s proposal is helpful in that it grapples with the idea of blame versus responsibility. But it ultimately suggests that reparations are a vehicle which we can use to balance the ledger and cut the thread of responsibility that we owe to one another—a sort of cosmic kiss-off.

Clearly, Krauthammer intended better. But here again is the delusion that a society afflicted with organic racial inequities is “colorblind”—or that cash transfers can make it so. Viewed in this light, reparations carries the whiff of a payoff, intended to forever resolve whites of their own nagging consciences. Perhaps worse, it lends itself to stereotyping blacks writ large as parody welfare recipients—indifferent to self-improvement and eager for the dole.

In this construct, reparations threatens to further atomize American society as much as heal it. It does nothing to heal the deeply ingrained legacy of race. On a practical level, whether someone profits from a cash grant depends greatly on their individual circumstances. Further, it ignores the enormous difference between say, a Sasha or Malia Obama—whose mother's family bucked disheartening odds to give the former Michelle Robinson and her brother a better life—and a child of poverty who lives in a bad neighborhood, goes to inferior schools, and who needs but lacks afterschool programs and adequate childcare.

Most African-American congressional leaders frame reparations differently. By and large, they aren't pressing for cash payments. Instead, as Barack Obama has suggested, "Society has a moral obligation to make a large, aggressive investment, even if it's not in the form of reparations checks, in the form of a Marshall Plan, in order to close those [racial] gaps." In a similar vein, Harvard law professor Charles Ogletree has proposed a program of job training and public works designed to further blacks while including the poor of all races.

But, for some, Ogletree's suggestion raises another problem—a suspicion that “reparations” might become just a rebranded version of other broad policy ideas. Says Duke University economist William Darity:

Universal programs are not specific to the injustices that have been inflicted on African-Americans. I want to be sure that whatever is proposed . . . as a reparations program really is a substantive and dramatic intervention in the patterns of racial wealth inequality United States—not something superficial . . . that is labeled as reparations, and then politicians say the national responsibility has been met.

Fair enough. But why dismiss out of hand programs which, by their very nature, will help address elements of racial disparity? For example, Cory Booker's "baby bonds" policy aims to help poor children by giving them a government-funded savings account which could reach $50,000. Kamala Harris proposes tax credits for working singles and working families; a housing credit for those who spend more than 30 percent of their salary on rent and utilities; and doubling the size of the DOJ's Civil Rights Division.

Elizabeth Warren proposes universal government-supported childcare, noting that its absence affects black families in particular, and that underpaid childcare workers are disproportionately nonwhite. She proposes directly tackling the racial wealth and housing gap through legislation which would provide down payment assistance to first-time home buyers in communities formerly subject to redlining; create more affordable housing; and assist homeowners still underwater on their mortgages because of the 2008 housing crisis.

The variety of these proposals—especially when measured against the daunting depth and complexity of the problem they seek to address—suggest that a commission is imperative. Says Coates, “It's not wrong to say we need to cure cancer—which is what I take to support of reparations to actually be—but we don't have a full diagnosis yet. If you can actually get a study which outlines what actually happened, what the needs are, with the debt actually is, and how it was incurred, then you can design programs that actually address it."

That’s a bracingly optimistic view. But it starts with its own imperative: an honest, heartfelt discussion through which Americans strive to leave politics behind, the better to appreciate our common humanity - not as a palliative, but as a rigorous social and moral re-examination which misses nothing. Only then can America, as it must, truly reach for what it should be.