The 1970s: A Down and Dirty Decade of Horror Filmmaking

How ‘Suspiria,’ ‘The Brood,’ and ‘Let’s Scare Jessica to Death’ helped define a decade of horror.

I’ve been watching independent 1970s horror movies for professional reasons—and as fortune would have it after viewing many, for personal reasons as well. Being terrified is a good distraction from other, more reality-based anxieties: Switching off the ever-depressing cable news channels following the 2016 election and switching on Danny Boyle’s zombie opus 28 Days Later was oddly relieving. That flick was a throwback to the strange, gritty horror flicks of the 1970s, a number of which I’ve had to watch more than once given that my hands instinctively fly to my eyes when the scary stuff starts. But they’re a pleasure to watch: Compared to many modern horror movies, they are both more daring and inventive because of their directors’ vision and their lack of technological innovations that we now take for granted.

To be clear—my scope is narrow. I’m not going to talk about massive, popular blockbusters like The Exorcist, Jaws, or Carrie. I’m also not going to talk about the slasher films that also emerged during the ’70s, mostly because I have seen few and, frankly, don’t enjoy them. What I will be talking about are films we might today describe as “elevated” horror, a term unknown in that more innocent era. I am drawn to ’70s horror movies because of their deceptive simplicity and rawness.

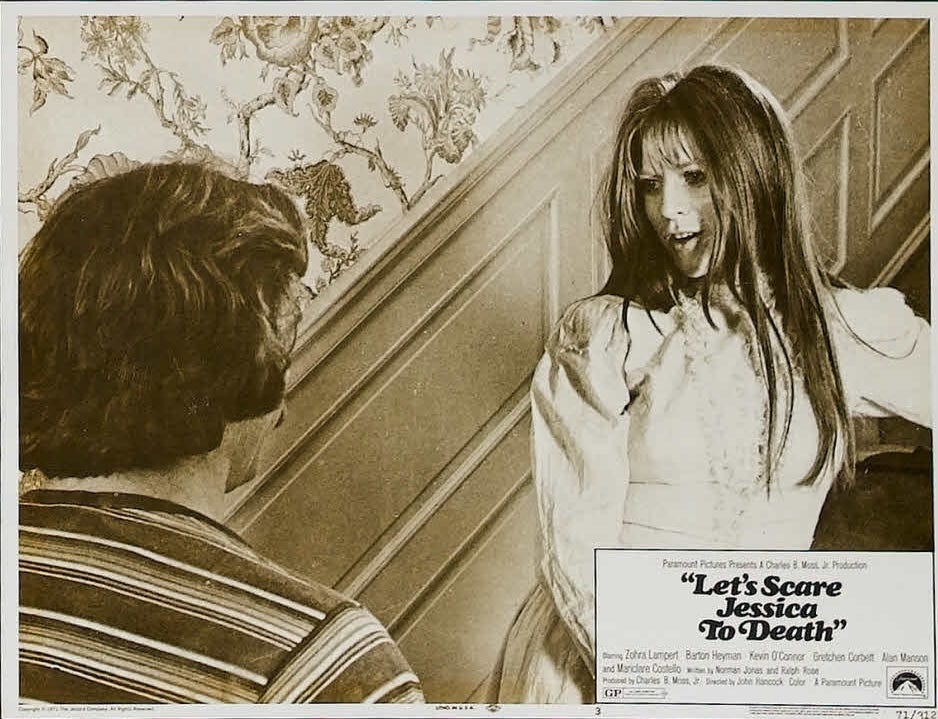

Let’s Scare Jessica to Death (1971), directed by John Hancock, begins with three hippies driving a hearse with a “love” sticker on its side onto a ferry in a rural town. The older locals are distinctly unfriendly to them. Jessica (Zohra Lampert), her husband Duncan (Barton Heyman), and their friend Woody (Kevin O’Connor), dismiss their inhospitality as small-town conservatism. While moving into the old Victorian house Duncan and Jessica have bought as a respite from life in New York City (where Jessica has just finished a stint in a mental hospital), they come upon a beautiful squatter, Emily (Mariclare Costello). Frightened at first, after proper introductions Jessica very kindly asks her to stay. Everything is kumbaya heaven: there is a sing-along, a seance, good food and good company. Soon afterward, however, things start to unravel in a terrifying way. The ethereally beautiful Emily might actually be a vampire.

Let’s Scare Jessica to Death’s cast is wonderful, particularly Zohra Lampert. It was director John Hancock’s first movie, and he gathered most of the cast from theater productions he had directed. This helps explain why it feels a bit like a play: There are only four main characters, and the he dialogue is focused and psychologically astute, exploring the stress between the status quo (in the form of past generations of vampires) and the era’s counterculture (our heroes) in this seemingly idyllic spot.

The budget was just $250,000, but its financial limitations make it special. There is one set: the house. For all I know, a friend lent John Hancock their country house for a month. I had never heard of anyone in the cast except for Zohra Lampert. The special effects are not that special: dummies floating in the lake; no fangs or that much blood, just slashes on townspeople’s necks and pallor on their transformed faces. At one point Jessica catches a “mole” and in a close-up we see it’s clearly a brown mouse. The actors look like they supplied their own wardrobe. Most of the lighting is ambient. With no air-conditioning in the old house, the cast’s faces often look sweaty. Zohra Lampert is gap-toothed and maybe a little too old to play a hippie. Barton Heyman is short and balding—not your typical leading man.

But the actors seem real. Duncan looks like a struggling musician. Woody looks like a handy, free-spirit. And Zohra Lampert glows with an inner goodness that makes you root for her. Her performance radiates nuance, empathy, and kindness, which makes it particularly tragic to see her optimism crumble in terror around her. In most of her scenes she is smiling through her pain and confusion. She tries to see the best in people, even if they turn out to be supernatural murderers.

Today, executives would recast Lampert with someone younger who has perfectly straight, dazzlingly white teeth. Duncan would be tall and handsome and have a full head of hair. Jessica’s matronly nightgown would be revealing lingerie. There would be jump-scares and gore and CGI. Lots, and lots, and lots of CGI. That brown mouse would’ve been a CGI mole, for sure.

It is tight and human and intimate. It’s a very simple story told in a straightforward, unfussy way. The editing by today’s standards is slow, Hancock lingering without cutting so the viewer can see each character’s body language in long shots. The sight of Emily’s lengthy fingernails sent a slight shiver down my spine. There are “day for night” scenes, and the sound is spotty. After Duncan becomes a vampire, the only difference is in his emotional stiffness and his pallor created solely by face powder.

But this lack of cinematic artifice isn’t distracting. In fact, it enhances the intimacy and pathos. These are real characters experiencing something extraordinary and horrific. Did vampires kill all her friends or did Jessica descend into madness and murder the people she loved the most? Let’s Scare Jessica to Death’s simplicity is its gift.

In David Cronenberg’s The Brood (1979), Frank (Art Hindle) has divorced his wife Nola (Samantha Eggar), who is under the care of a controversial psychiatrist, Hal Raglan (Oliver Reed). Hal practices “psychoplasmics,” a process that creates bizarre physical transformations but is supposed to affect some kind of catharsis in his patients. Frank believes his ex-wife has physically abused their daughter Candice during her visitations. Meanwhile inhuman, dwarf-like creatures terrorize and slaughter people close to Candice and Frank, like Candice’s grandmother, grandfather, and teacher. The murders seem to coincide with Nola’s therapy sessions. And there is a reason for that: These relentless killer-dwarves are literal outgrowths of Nola’s rage at the people in her life she considers her tormentors. The Brood is a terrifying meditation on parenthood, divorce, generational trauma and what happens when what used to be love transforms into hate.

Again, this isn’t a sumptuous, beautiful movie. It’s full of ’70s rawness. The Canadian winter light is harsh and flat with suffocating, endless snow. Every day is overcast. The picture quality is grainy. People don’t look their best in that angle of light and they’re not supposed to. Makeup is minimal. The only person who looks beautiful is Nola and this is used against her in the end, as if her beauty were another aspect of her sickness.

The warmth of Hal Raglan’s 1970s post-and-beam house in the middle of the woods is a huge contrast in style and feeling from the rest of the movie: all variations of brown and orange inside compared to the vast, sterile whiteness outside. When Hal lets Frank into his house dressed in a short robe and Oomphies slippers, the glow inside highlights the chill outside.

Several of the cast’s performances are clunky and stiff; Art Hindle is blandly and forgettably handsome, like a guest star on an episode of a B-list 1970s detective show, and his reaction to the inconceivable horror unfolding around him is almost nonplussed. But I feel it is on purpose. “Frank” is supposed to be a blank slate, a non-actor, someone who could be a stand-in for anyone. He is absorbed into the action, he doesn’t affect it. And Candice is supposed to be a lonely, strange child with a flat aspect. It’s not entirely surprising that the mom responsible for half of her DNA generates horrific creatures who resemble her.

If this movie were made now, those in charge would demand a more appealing child actor who would tug at our heartstrings. But sympathy isn't the point. In fact, it’s the opposite of the point. Cronenberg’s genius is to present this movie “objectively,” with as few flourishes and the least warmth possible so that the grotesque horror of the situation stands out.

All the horrific dwarf-like creatures were real people underneath practical makeup by genius Rick Baker (American Werewolf in London, folks), adding a little extra creepy verisimilitude to the setting. Again, one can only imagine how lame the modern CGI iterations of these beings would be today.

The most effective way I can differentiate 1970s independent horror movies from today’s is to compare the 1977 Suspiria with the 2018 Suspiria. Although I think both are engrossing, they couldn’t be more different in style, tone, pace, and story.

Dario Argento said Suspiria (1977) was his twisted version of Snow White, itself a pretty twisted story. Argento’s take concerns a young woman, Suzy Bannion (Jessica Harper), who comes to Germany (although the whole movie looks distinctly Italian) to study with the prestigious Tanz dance company. She arrives in a downpour to see one of the dance students running in terror away from the school; that student subsequently dies in the most mysterious and horrific way. Suzy is delighted and honored to be given free room and board until strange occurrences happen to her and her friends. She soon discovers that this company is run by a coven of witches, and her demise is part of their devious plan.

Luca Guadagnino’s Suspiria (2018), other than being set at a German dance company (really in Germany) with the same character names (and a cameo appearance by Jessica Harper), is an entirely different sort of movie. Suzy Bannion arrives at Tanz with an already broken spirit, haunted by the dying breaths of her mother who called her “my curse.” She begs for a chance and is accepted into the company by the lead dance teacher, Madame Blanc (Tilda Swinton) even though she has no formal training. She soon becomes Blanc’s prize student: she chooses Suzy to be the lead dancer in a piece (that is really a ceremonial incantation) they will perform in public after the former lead, unbeknownst to the other dancers, dies gruesomely as the result of a spell.

As with most 1970s horror films, the original Suspiria is down and dirty at one and a half hours. Even though the 2018 version has more frenetic pacing, it is an hour longer than its predecessor. The editing in the modern version doesn’t linger on shots like the original—for example, the very odd and seemingly random scene in which Suzy and Sarah float in Tanz’s giant Roman indoor pool. It is “slow”; bizarre and unique.

The original is almost entirely from Suzy’s perspective, just like Snow White is the main protagonist in her story. However, in the latter version, we shift perspectives between four main characters: Suzy; Madame Blanc; Suzy’s best friend, Sara; and an elderly psychiatrist who treated one of the dancers who disappeared. Because of this, the 2018 version is a psychologically richer film. But it’s also less fun.

Sometimes Argento’s Suspiria feels not just like Snow White, but also Alice in Wonderland. The bright primary colors, especially the geometric stained-glass dome that impales one of the dancer’s friends, remind me of playing cards. Argento’s DP used “imbibition Technicolor” to amp up the colors to unnatural brightness. He also used a special lens to stretch out the image to widescreen and then shrink the image vertically, which gives the interior shots a nightmarish, claustrophobic feel. To add to the artifice, he dubbed the actor’s voices or used ADR for the English-speaking cast so the dialogue sounds a little off. Suzy walks innocently into this coven of witches and we as the audience are discombobulated as well. The exterior of the Tanz building feels like a fake wooden facade because it was. The synthesizer music by Goblin repeats like a hypnotic spell throughout Suzy’s journey. It’s like an exaggerated heartbeat and is both spooky and absurd. Everything about this movie looks a bit off-kilter and ersatz; even the blood looks like bright, red paint. And of course, other than the choice of lenses and the film development process, almost every other nightmarish vision is made with practical effects and makeup. Most of the performances are almost camp. It is deliberately garish. The cinematography is stunning but also vulgar. The various dreadful ways the witches kill their victims are more like turning the pages of a brilliant and grotesque pop-up book than watching a film, but this story is more about style than pathos. We don’t know enough about the inner workings of anyone’s psyches to care too much about them. We go along on this fever dream of a journey. After killing the head witch, Elena Markos, which in turn kills the rest of the coven, Suzy runs from the imploding dance school into a downpour with a smile on her face, like all heroines in fairy tales, unscathed and untraumatized.

Although the 2018 Suspiria has its terrifying moments as well, it is mainly a feminist interpretation about guilt, trauma, politics, loss and destiny. Instead of being an innocent victim, Suzy is complicit. Madame Blanc is complex and conflicted, both a tormentor and a surrogate mother to the seemingly lost Suzy. She also ends up being a martyr. The elderly psychiatrist, also played by an uncredited Swinton, is torn apart by guilt. 1977 Berlin is similarly torn apart politically, East and West. Suzy’s best friend at the company, beautifully acted by Mia Goth, is entirely well-rounded and sympathetic so we actually care when the witches kill her. Death and loss loom over every moment, giving the movie a weight that doesn’t exist in the original. Thom Yorke’s score is a bit heavy-handed and doesn’t have the same bizarre hypnotic effect as Goblin’s. The drab colors (until the final dance performance and climax, which of course indulges in CGI effects aplenty) only add to the gloominess. And this version has absolutely no sense of humor. It’s a serious movie, doncha know! I thoroughly enjoyed it but it didn’t worm its way inside me like Argento’s did. It felt more like a psychodrama than a nightmare, and in that way it takes fewer chances and is actually more conservative than the 1977 picture. Dario Argento isn’t a fan of the modern version. Even though I think it’s accomplished and complex, I can understand his feelings: while Luca Guadagnino considers it a love letter to Dario Argento, Argento probably feels it’s a love letter to someone else sent to him by accident.

And now I will be a typical myopic actor. If I were lucky enough to have been offered a chance to be in either production, which would I prefer? And I will again engage in a typically actorish hedge by answering “both.” The 2018 Suspiria offers up more actual emotional depth, and I’d have the opportunity to work with great actors like Tilda Swinton. I mean, how could I possibly say no?

But being in the original 1977 Suspiria would be an absolute blast. Insane, but a blast. When I was younger I acted in many bizarre experimental theater productions off-off-off (etc.) Broadway. Three were in a rundown theater in SoHo (which has been renovated and is now a fancy theater in SoHo) that at the time had many seats cordoned off because they were broken. I didn’t even understand what I was saying most of the time, but acting in these plays was an adventure. The productions were absurdly low budget, and because of this we were forced to be extra tricky and inventive. And we were! Our director’s imagination and visual sense were extraordinary and once we were in front of an audience, no matter how small, they were enraptured and actually taught me the nonsense we were performing made sense. There was one scene where I played an angel teaching the Devil the hokey pokey and at the end I jumped on his back and rode offstage. I thought it was absurd and funny, which it was.

But over and over, the audience found it moving—I heard them react. And I realized that my angel was soothing that Devil. She was undaunted by his ferocity. He softened and let her love and help him. I was so grateful to that audience for teaching me that we were all in this experience together. And I think I would have a similar experience acting in the 1970s Suspiria. I’d have no idea what I was doing or what effect I’d have on the audience until I saw it together with them in a movie theater. They would instruct me about what I had done by their reactions. My job would be to submit to a mad-genius director like Dario Argento and trust his instincts. His bold, raw and surreal 1970s sensibilities would make his nightmare fairy tale my dream job.