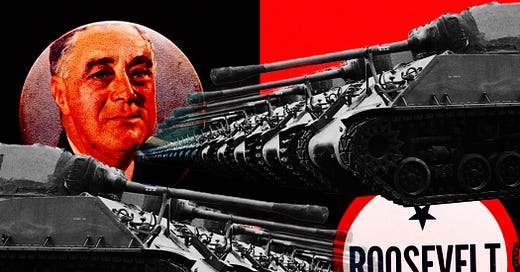

The ‘Arsenal of Democracy’ Once More

In sending military aid to Ukraine, America’s values and security interests are aligned.

ON THE EVENING OF DECEMBER 29, 1940, in one of his famous fireside chats, President Franklin D. Roosevelt warned the American people of the threat posed by Nazi Germany, fascist Italy, and imperial Japan. While the Neutrality Acts passed in the 1930s prevented the United States from engaging in the war then raging in Europe, FDR and his congressional allies had sought to prepare the country for eventual involvement, including enacting the first peacetime draft. Now it was time for a new step: He called on industry leaders to increase production of weapons and munitions that could aid the countries being attacked by the Axis powers.

“The people of Europe who are defending themselves do not ask us to do their fighting,” Roosevelt said.

They ask us for the implements of war, the planes, the tanks, the guns, the freighters which will enable them to fight for their liberty and for our security. Emphatically, we must get these weapons to them, get them to them in sufficient volume and quickly enough so that we and our children will be saved the agony and suffering of war which others have had to endure.

Roosevelt understood that it was in the best interests of the United States to support other democracies. “Our own future security is greatly dependent on the outcome” of the war in Europe, he said, and “our ability to ‘keep out of war’ is going to be affected by that outcome”—and so the United States “must be the great arsenal of democracy.”

Today, Ukraine is running out of ammunition. Congress has wasted months on negotiations that a subset of Republicans have sought to stymie and stall. Donald Trump has reportedly said he wants to pull the United States out of NATO, and he has openly encouraged Vladimir Putin to invade other European nations. The time has come for the United States to reject this isolationist sentiment and once again accept its role as the arsenal of democracy.

IN THE FIRESIDE CHAT, Roosevelt articulated two reasons why the United States should be the arsenal of democracy. The first was ideological. “Never before since Jamestown and Plymouth Rock has our American civilization been in such danger as now,” he asserted. The war might seem far away, he explained, but the “Nazi masters of Germany have made it clear that they intend not only to dominate all life and thought in their own country, but also to enslave the whole of Europe, and then to use the resources of Europe to dominate the rest of the world.” Americans could not hide inside an isolationist bubble, content that the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans would protect them from all threats.

FDR did not suggest direct military involvement in the war—public opinion would not support that until the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor a year later. But he argued that American democracy thrived or failed in step with other democracies around the world and called on Congress to support the embattled democracies, especially the United Kingdom, in a shared fight against the forces of authoritarianism before the fight arrived on American soil.

In addition to Roosevelt’s high-minded liberal internationalism, there was also a measure of narrow self-interest in his proposal. “We must have more ships, more guns, more planes—more of everything,” FDR proclaimed. Making those ships, guns, and planes would require American resources, American labor, and a lot of work for the American businesses that would sell the products to the government. The enactment a few months later of FDR’s Lend-Lease proposal also meant the government would buy huge amounts of food to send abroad, especially to the Soviet Union. Every bullet and bushel sent to our allies created jobs and boosted the American economy of the 1940s.

ALTHOUGH FDR’S EXAMPLE IS PERHAPS the most familiar, he was neither the first nor the last president to strengthen the American economy through strategic wartime production. In 1798, President John Adams offered economic and political support to Saint-Domingue (now Haiti). The agreement amounted to recognition of the new nation, the first time a white American government recognized a black-led nation.

Adams had three motivations for this move. First, Caribbean trade was a lucrative opportunity too enticing to pass up. The new United States, having lost access to privileged trade within the British Empire, was desperate for trading partners. Second, supplying Saint-Domingue weakened France, which had been attacking U.S. shipping during the Quasi-War. In other words, Adams supported an enemy of our enemy. Finally, Adams supported another nation fighting for its independence. Adams’s support was limited, however. He never dispatched American forces to aid Louverture and never considered any form of defensive alliance.

Neutrality should not be confused with isolationism—neither in Adams’s time nor in ours. He had supported neutrality since the Declaration of Independence, and ending the Quasi-War with France in the 1800 Treaty of Mortefontaine was one of his crowning achievements as president. Adams also cultivated trade relationships and believed the that future of the United States depended on active economic engagement with the rest of the world. Like FDR nearly two centuries later, Adams found a way to align America’s interests and values in his foreign policy.

AMERICAN NATIONAL SECURITY AND INDUSTRIAL MIGHT were also famously married during the Civil War.

Many of the improvements associated with the Gilded Age had their roots in the Civil War, including government-backed fiat currency, the expansion of railroads, the explosion of industrial production, and the rapid spread of the telegraph. It’s no coincidence that the transcontinental railroad project started in 1863—the midpoint of the war—and durable telegraph cables connected New York to Europe in 1865.

None of this, of course, means that the death and destruction of the Civil War or any other war are worth it for the technological, industrial, and economic improvements. It’s preferable to gain the advantages of wartime innovation without the instability, suffering, and death—as was the case for much of the Cold War. The United States never fought a direct war with the Soviet Union, but government investment in defense led to the Interstate Highway System, space exploration, jet airlines, nuclear power, and the internet, among many other inventions and projects.

THE UNITED STATES TODAY FACES SERIOUS, long-term threats from near-peer competitors in China and Russia. The United States needs to prepare itself for the possibility of a major war, but even if one never breaks out, the ongoing wars in Europe and the Middle East and Taiwan’s chronic endangerment demonstrate how reliant America’s democratic allies are on its industrial output, especially for defense.

We are not in this fight alone. Earlier this month, the European Union crafted a new long-term aid package for Ukraine, which promises to deliver $54 billion over the next four years. While the United States remains the largest single donor by gross dollar value, Estonia, Latvia, and Norway have all contributed over 1 percent of their GDP. For comparison, the United States has contributed 0.37 percent of its GDP.

By providing weapons to Ukraine and our other allies, we will be aiding fellow democracies, acting in our own security interests, and boosting our own economy. (Remember that to replace materiel sent to Ukraine, the U.S. government places orders with American companies for products built by American workers.) The bill passed by the Senate and awaiting action in the House offers a renewed opportunity to turn away from isolationism and to embrace once again—for our own good and for the good of the world—our role as the arsenal of democracy.