The Art of Fibers and Fabrics

Textiles, cords, and knots can be so much more than ‘craft.’ A new exhibition celebrates creators long neglected because of their preferred medium.

Subversive, Skilled, Sublime: Fiber Art by Women

Renwick Gallery, Washington, D.C.

through January 5, 2025

RUGS AREN’T JUST TO WALK ON ANYMORE, and blankets don’t just keep us warm. These fabrics have risen from floors and beds to museum walls. Earlier this year, the National Gallery of Art put on a huge exhibition, “Woven Histories: Textiles and Modern Abstraction,” in which fabric artworks were framed on walls and showcased in artifact vitrines—a direct challenge to the old tendency to dismiss textiles as marginalized “women’s work.” The Museum of Modern Art PS1 in Queens recently jumped on the textiles-as-art bandwagon with an exhibition displaying more than fifty of artist Pacita Abad’s signature “trapuntos,” or quilted paintings. And the Textile Museum in Washington, D.C.—which next year marks its centennial, making it one of the oldest such museums—has long mounted shows that put front and center the artistry of textiles from around the world.

The elimination of barricades guarding art from craft reflects a larger shift in how the art market operates. In the postwar decades, art criticism played a major role, with members of the art world rushing to kiss the ring of critic Clement Greenberg. Greenberg was famous as the “art czar” who proselytized the importance of abstract expressionism, and in particular the significance of Jackson Pollock. Greenberg also popularized the idea that art and craft belonged to two distinct and unbridgeable worlds. You could hear his loud sniff of disapproval that any utilitarian fabrics would be treated as “art.”

But such proclamations and prejudices are as obsolete today as the “art czars” themselves. Cultural criticism today is ruled by a sense of interpretation rather than judgment, and the only response to lingering questions about art vs. craft is, “Says who?” Or, “Who cares?”

A Smithsonian museum has special relevance in this discussion as a national showcase of craft today. Established in 1965 to be “a gallery of arts, craft, and design,” the Renwick Gallery in Washington, D.C., which faces the North Lawn of the White House, has just opened an exhibition that adds an exclamation point to the importance of woven artworks. Subversive, Skilled, Sublime: Fiber Art by Women describes how fiber has long inspired women artists but “was often dismissed as domestic work and therefore inconsequential to the development of 20th-century American art.” This exhibition addresses the historic marginalization of fiber in contemporary art-making by showcasing the works of 27 artists who mastered fiber art “and transformed humble threads into sublime creations.”

“Dating from 1918 to 2004,” says a museum press release, “the 33 works in this exhibition range from sewn quilts, woven tapestries and rugs, and beaded and embroidered ornamentation, to twisted and bound sculptures, and mixed media assemblages.” All are drawn from the collections of the Smithsonian American Art Museum.

The exhibition’s curatorial team was composed of Virginia Mecklenburg, senior curator of the Smithsonian American Art Museum; Mary Savig, the Lloyd Herman Curator of Craft; and Laura Augustin Fox, curatorial collections coordinator at the Smithsonian American Art Museum. Mecklenburg told me that their goal was “always to foreground the artists—we wanted these amazing women to speak for themselves rather than be mediated through a curatorial lens.” Instead of a curatorial ‘voice of God’ telling visitors what they are seeing, the individual wall labels for each work are in the artist’s own words, and taken from interviews in the Smithsonian’s Archives of American Art collection. In most instances, the curators have also included a picture of the artist. Mecklenburg said they wanted visitors “to feel that they are interacting as directly with the artist as possible in the show.” For this viewer, these wall labels do exactly that—a welcome contrast to museums that present exhibition labels as didactic statements of “importance.”

For the curators, a major driving force for this exhibition was that “critics and art world figures (mostly male) ignored and dismissed fiber art as ‘women’s work,’ not worthy of the same level of attention as paintings, sculpture, etc. It was ‘craft’ rather than ‘art.’” To smash that gendered hierarchy, they wanted to show that fiber art is not only innovative and amazingly creative, “but also an important medium of expression that addresses the whole range of human experience, especially as experienced by women.” The resulting exhibition encompasses a cross-section of works by Native, African American, Latina, and Asian American artists that share social and family commonalities, but also evoke “subversive feminist ideas” inspired by marginalization and exclusion.

There is a vibrant atmosphere of individual creativity throughout this exhibition. The artworks radiate personal achievement; there is no blot of “sameness” among these fiberworks. Instead, a rollicking sense of the unexpected is launched at the outset, starting with Claire Zeisler’s Coil Series III—A Celebration (above). This is a freestanding structure made of hemp, wool, and wire, created by the artist and her assistants in 1978 using knotting and wrapping techniques to meticulously wrap thousands of threads around galvanized wire.

Other highlights of the exhibition exemplify the variety of fiber and textile artworks today:

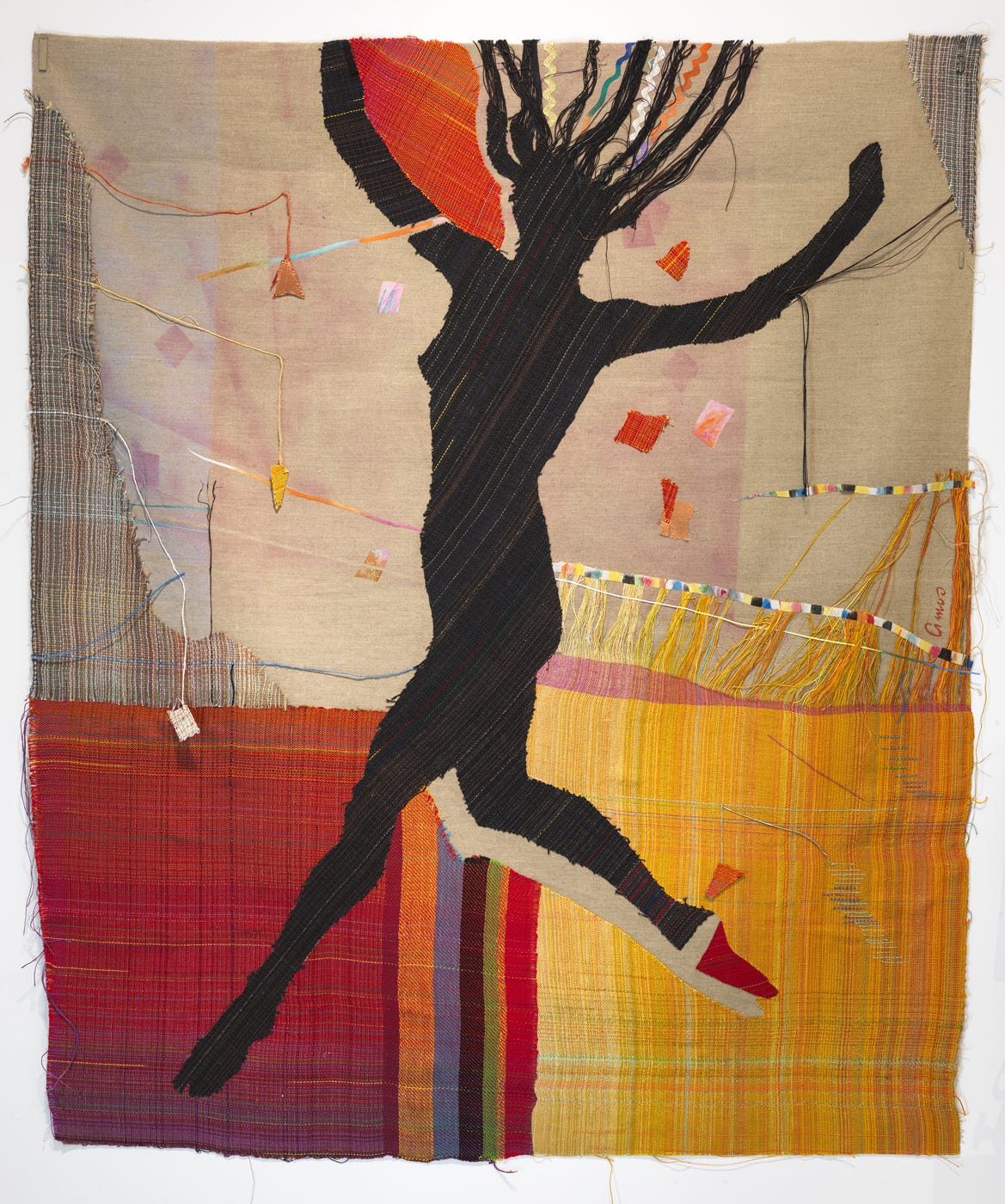

In Winning (1982), Emma Amos has created an exultant leaping woman using a patchwork of woven swatches, threads, and ribbons.

Lenore Tawney’s Box of Falling Stars (1984) is composed of cotton canvas, linen thread, acrylic paint, and ink. She calls this work an example of “vertical weaving”—instead of a loom, she uses a canvas support and pulls single threads through the canvas, sewing each thread with a knot in a process repeated thousands of times. The shimmering threads are meant to emulate how the heavens hold and diffract light.

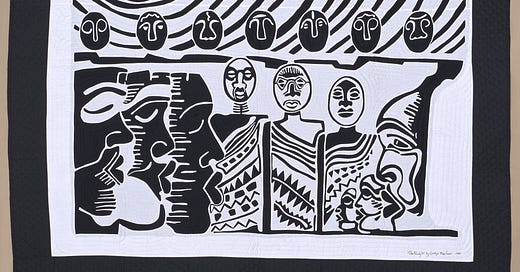

Faith Ringgold was famous for her narrative quilts, and she is here represented by The Bitter Nest, Part II: The Harlem Renaissance Party (1988). This is a painted quilt portraying an imaginary family having dinner with figures from the Harlem Renaissance, including Alain Locke, Langston Hughes, and Aaron Douglass.

In addition to flat art works like painted quilts, the exhibition features such beadworks as Joyce Scott’s Necklace (1994), an oversized necklace imbued with Native American, African American, and West African influences.

What impressed me overall was how well this exhibition was curated—the artworks were fascinating, there was an easy flow among them, and access to artist statements forged a visceral connection with visitors. As Mecklenburg told me, “We started with the conviction that each work is important on its own terms and in its own particular context. We were inspired by what we learned in the oral histories in the Archives of American Art. We didn’t try to conform to predetermined themes, but let the groupings flow organically from the artworks. And the title is a result—some of the work was subversive when it was made, all of it is skilled, and all of it is absolutely sublime.”

What a classic description of the curator’s art!