The Beer Night Riot, 50 Years Ago: What Was That America Like?

The melee, the mayhem, the metal chairs.

WHEN MY FRIEND OF DECADES JIM KANDER called me a few weeks ago and told me the fiftieth anniversary was coming up, I didn’t have to ask him what he was referring to. I knew it was the “Beer Night Riot” in Cleveland on June 4, 1974—a night of sports infamy Jim and I got to experience firsthand.

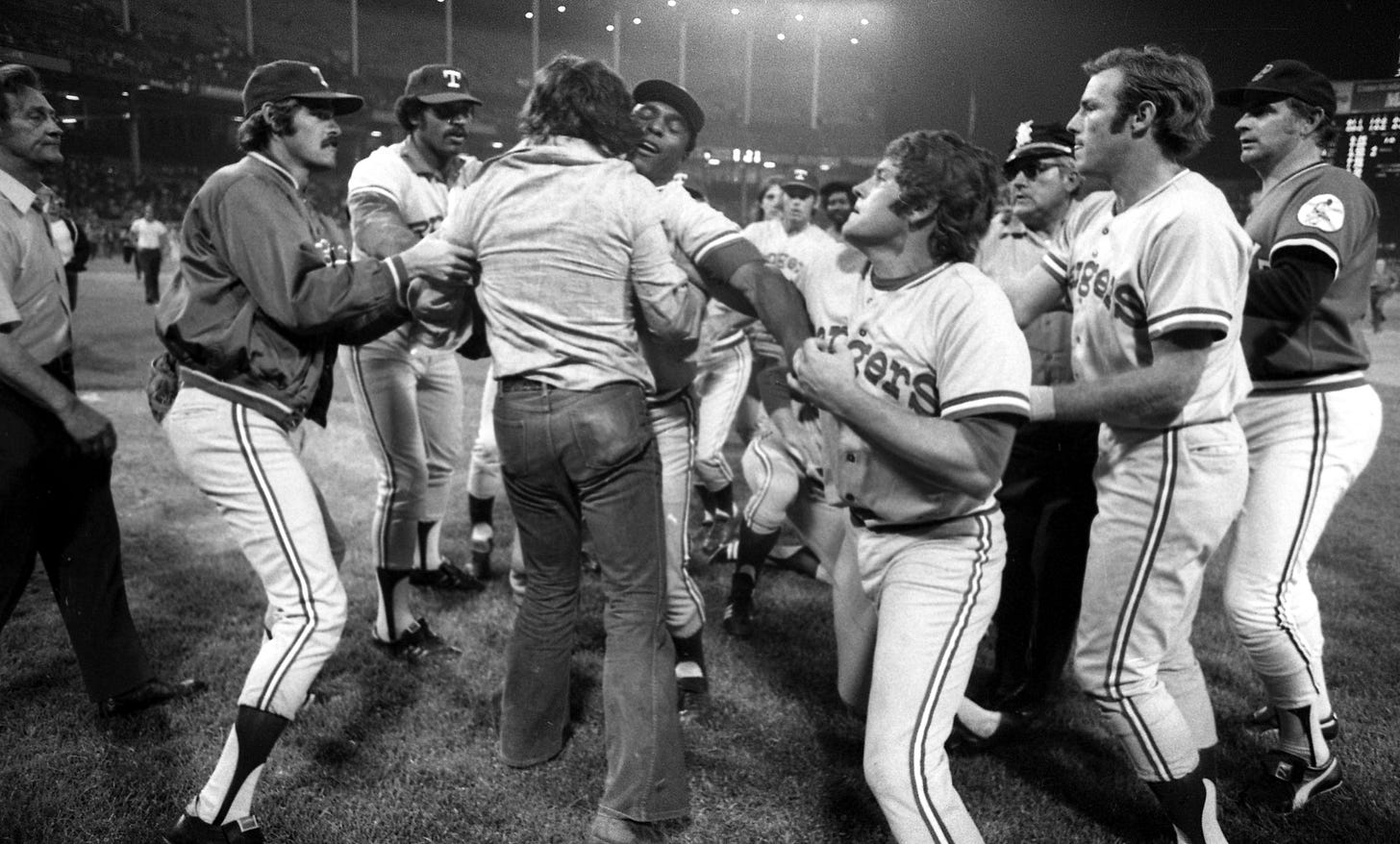

The events of that night weren’t televised or filmed as moving pictures, which is why all these years later many don’t know about the Beer Night Riot. But it deserves to be remembered for the wild night it was—a beautiful summer night baseball game between the Texas Rangers and Cleveland Indians where fans got so drunk on unlimited 10-cent beers that they stormed the field with bottles and knives. They were acting so crazy that the players for both teams had to counter-storm the field to protect themselves. Many of the players did so with baseball bats, although those didn’t offer much help against the bottles and chairs raining down on them from the upper decks.

Ken Aspromonte, Cleveland’s manager at the time, remembered the moment during an interview with Cleveland magazine for a recently published oral history of the riot. “I said, ‘We gotta go help [Texas Rangers manager] Billy [Martin].’ We figured his 25 and my 25 could take care of it. The people were on the field swinging like hell, but mostly missing because they didn’t know where they were.”

“We got hit with everything you can think of,” Billy Martin recounted afterwards. “Chairs were flying down out of the upper deck. Cleveland players were fighting their own fans. First they were protecting the Rangers and then they were fighting to protect themselves. Somebody hit [Cleveland pitcher] Tom Hilgendorf with a chair and cut his head open.”

“That’s probably the closest we’ll come to seeing someone getting killed in the game of baseball,” Martin told the Plain Dealer. “In the 25 years I’ve played, I’ve never seen any crowd act like that. It was ridiculous.”

The players escaped and it took nearly an hour to get the hundreds of fans off the field, capping off a night that started as an entertaining debauch before turning scary. Jim and I had watched it all. We were wide-eyed teenagers who had just finished our first year of high school, and in the space of an evening, we’d gotten a kind of ad-hoc street supplement to the year we’d just spent in class. We had seen around twenty streakers, many more than the seven claimed as a world record at a sporting event in 2007, a far more polite year than 1974. One woman showed her breasts while trying to kiss the home plate umpire. Martin, the Rangers manager, egged the crowd on by throwing crushed gravel at them, which in hindsight probably struck him as a poor decision. Then there was the stumbling drunk throwing metal folding chairs from the upper deck onto the players trying to stop the melee in left field. It was mayhem all around, and all the while, the beer kept flowing. The only limit on consumption was four beers per person per visit to the pourers. (Of course, there was no limit on repeat trips.) The crowd of more than 25,000 is estimated to have consumed over 60,000 cups of draft beer that night.

SOME SPECULATE THE BEER NIGHT RIOT was a product of the instability of the ’70s. Streaking had just come on the scene, with one naked man running behind actor David Niven at the Oscars in April that year—“It is quite obvious the whole world is having a nervous breakdown,” the actor had just said—and Ray Stevens’s comic novelty song “The Streak” reaching number one on the Billboard Hot 100 Singles chart in May.1 These were funny moments, but Niven wasn’t wrong about the world then. The Yom Kippur War and subsequent oil embargo and energy crisis had all taken place the previous year. President Richard Nixon was feeling the heat being turned up on Watergate and would resign in August; he’d crushed George McGovern in the presidential election only two years earlier. There was still racial animosity in the air, a hangover of sorts from the cultural movements of the 1960s, and big numbers of baby boomers born in the mid-1950s were coming of age. That meant there were a lot of adolescents around, full of hormones and energy.

Darkest of all in the local context was what had happened a few years before just forty miles down the road from Cleveland: the Kent State killings.

It was a grim scene. But those of us who were at the ill-fated ball game can confirm that all this cultural depravity and geopolitical instability had little to do with what happened at Cleveland Stadium that night in early June 1974.

“It was about revenge,” said my friend Jim, a longtime communications company executive who has lived in the Cleveland suburbs for decades.

I knew what he was talking about. “The beer put gasoline on the fire, but this was real simple,” he continued. “Indians fans thought the Texas Rangers had wronged our team the week before, and we were going to get back at them.”

TO GET A FEEL FOR HOW BAD the Cleveland fans at the stadium acted, consider this observation from Tom Grieve, who played in the Rangers outfield that night and remembers home plate umpire Nestor Chylak being “so mad that . . . he had his face mask and was slamming it on the light bulbs, smashing each one of them. He was just disgusted.”

As Fort Worth Star-Telegram baseball writer Mike Shropshire wrote in his 1996 book about covering the Rangers during their era as the worst Major League team in history, Chylak got even madder the longer he thought about what he had just witnessed.

“ANIMALS! FUCKING ANIMALS! THAT’S WHAT ALL THESE FUCKING PEOPLE ARE!” Shropshire remembers Chylak shouting to the press after the game. “I even saw a couple of knives out there in that mob. Then they [the Rangers] charged out, they had to because those fucking animals wanted to kill somebody. I personally got hit with a chair and rock.”

What motivated the crowd’s rage? Well, a week prior, the Rangers’ Lenny Randle had set off a bench-clearing brawl by giving a forearm shove to a pitcher fielding his bunt and then crashing into the first baseman. Rangers fans then threw beer on Indians players as they came back to their dugout. That’s it.

Martin, the Rangers manager, said in an interview before the June 4 game that he wasn’t worried about the possibility of “retribution” in Cleveland because “they don’t have enough fans there to worry about.” But the city was abuzz. Local sport-talk radio host Pete Franklin claimed fans could exact “revenge” on June 4—and guess what, it would be beer night that night, too. The media was getting caught up in the hype they were creating. In a Cleveland Press pregame writeup, the paper proclaimed that fans should “Rinse your stein and get in line. Billy the Kid and his Texas gang are in town and it’s 10-cent beer night at the ballpark.” The crowd that showed up was double the size for an average Tuesday night game.

I can’t go into all the craziness my friend and I witnessed. It started out with a couple streakers on the field between innings, but then there were ten, and then twenty—an entire nude platoon. Grieve hit a home run in the fourth inning, and a naked streaker ran the bases with him. If things had stayed at this level, the June 4 game might have been remembered differently—Prelapsarian Night at the Ballpark, perhaps. But people were also throwing cherry bombs and M-80s on the field. (The Rangers had to come into the main dugout from the bullpen because of the danger posed by the fireworks thrown at them.) Indians reliever Tom Hilgendorf got hit with a chair thrown from the upper deck and was put on the disabled list after the game.

“I bet I had five or ten pounds of hot dogs thrown at me at first base,” Rangers first baseman Mike Hargrove (and later Indians manager) said. “Had a gallon jug of Thunderbird wine land about ten feet behind me.”

While the crowd that night was huge, not all the fans in attendance were drunk and disorderly. Lots of us were just there to have a good time. It was really just a few hundred who caused the craziness. My friend Jim and I saw a difference in who showed up for the game, and we often wondered who the newcomers were. They weren’t the usual sports fans we were used to seeing. Shropshire noticed this difference, too. This was what the sportswriter remembered:

On the commuter train from Hopkins Airport into downtown it became clear that something really special—or at least different—was looming at the ballpark on 10-Cent Beer Night. At each stop the train was filling with young people obviously headed for the game to take advantage of the promotion. Everybody was wearing Indians baseball caps and Indians batting helmets. As a court-certified expert on brain abuse, it was my educated guess that most of these fans were already loaded on Wild Turkey and whatever medicine it is that truck drivers take to stay awake on long hauls. Their condition suggested that they might be on their way home from, and not on their way to, a 10-Cent Beer Night game. It appeared that many had been preparing for this event for perhaps a couple of days.

Many years later, in the mid-’90s, I ran into the late Tim Russert, the Meet the Press host, while in Washington. Seeing as he was from Buffalo and I was from Cleveland, sports was a comfortable topic of conversation. It took only a few minutes for us to realize we had both been at the Beer Night Riot. He had been a law student in Cleveland at that time.

“I had two dollars to my name for weeknight entertainment night while in law school, and I was able to do the math,” Russert told me. “Getting drunk and baseball for $2. Looked like the best deal ever,” he said.

Thousands of Clevelanders had made similar calculations. Bleacher tickets were 50 cents back then in Cleveland, and during the promotion, fifteen 10-ounce beers could be had for $1.50. This means that on June 4, 1974, fans could purchase a ticket to the Indians-Rangers game plus fifteen beers for $2. The inflation calculator says that $2 in 1974 is worth a little under $13 now. Can you imagine any MLB team today offering a ticket to a game and fifteen beers for $13? It’s hardly surprising that Nixon’s “Silent Majority” and gangs of baby boomers coming home from college got together that night to turn the world upside down.

“I will always remember that night,” Russert told me. “Changed how I saw the world of politics, and so many other things. I saw what the average Joe was capable of. Kind of scary.”

IT IS KIND OF SCARY, what the average Joe is capable of. The point has been on my mind a lot lately as commentators and pundits have warned of the threat of social and political upheaval as the endgame for this year’s election. After former President Donald Trump was found guilty last week of 34 felony counts related to covering up hush-money payments to Stormy Daniels in the leadup to the 2016 election, the former president’s supporters took to social media to promise revenge for the verdict. Reuters covered some of their comments, reading into them the possibility that “violent retribution” could be on the horizon.

“1,000,000 men (armed) need to go to Washington and hang everyone. That’s the only solution,” wrote one pro-Trump poster on a MAGA-aligned website. Wrote another: “Trump should already know he has an army willing to fight and die for him if he says the words . . . I’ll take up arms if he asks.” Other armchair guerrilla fighters offered more of the same.

Americans seem to talk in public (or virtual public) about political violence more often than ever, but compared to the 1960s and 1970s, actual political violence strikes me as quite rare. I am curious why the American people show physical outrage so rarely in spite of constant opportunities to engage in it. For example, I have been to more than a dozen Trump rallies over the past few years and I’ve never seen any kind of upheaval or fighting at them. It’s more like the circus coming to town than a paramilitary gathering, and the locals are more curious to see what it is than they are interested in shouting and marching. The media has tried to portray Trump rallygoers as having a “mob mentality,” but they never really have gone down that road.

But the January 6th attack on the Capitol was different. That day saw premeditated violence enacted to serve a purpose. The crowd wanted revenge because they bought into the “Big Lie” and the “Stop the Steal” movement. Trump supporters acted one way at his rallies and another when encouraged to disrupt Congress and interrupt the certification of electoral votes.

The parallel with cheap beer and craziness at a sports game is obvious. Plenty of beer nights had been held before and since June 4, 1974—there was another similar promo only a month later—but only one turned the fans into “animals,” as the umpire Chylak angrily called them. The key difference? The motivation. Revenge is the match that lights the tinderbox.

“He ain’t lewd / He’s just in the mood to run in the nude.”