The Bucha Atrocities and the Kremlin Apologists

Commentators suffering from Ukraine Derangement Syndrome are distorting and distracting from the horrible facts.

THE GRUESOME DISCOVERIES in Bucha, Trostyanets, and other Kyiv suburbs newly freed from Russian occupation have shifted the discourse on Russia’s war in Ukraine, putting the focus on Russian atrocities against the civilian population. By now the horrific photos and videos—bodies buried in mass graves or lying by the roadside, some victims with hands tied execution-style behind their backs—have been seen around the world and have shocked the conscience of everyone except the habitual Kremlin apologists. Survivors’ harrowing accounts of rape, torture, looting and other war crimes by Russian forces are also emerging. Inevitably, there are also the skeptics warning about propaganda, fakes, and emotional reactions. How, in the midst of a crisis with passions running high, do we respond to news of appalling tragedies?

This is hardly the first time that atrocities and war crimes have been reported since Vladimir Putin’s invasion of Ukraine on February 23. On March 16, the Donetsk Regional Theater of Drama in Mariupol, where over a thousand people were sheltering—and “children” was written in large letters in the front and the back of the building—was bombed, leaving as many as 300 dead. The Russian state-owned media, and their American amen chorus, blamed Ukrainian extremists from Ukraine’s supposedly “neo-Nazi” Azov Regiment. (While Azov has a shady history—it started out as a volunteer battalion with ties both to neo-Nazis and to Jewish billionaire and politician Ihor Kolomoyskyy—most experts believe its current incarnation is not extremist.)

EARLIER, ON MARCH 10, there were shocking reports of a Russian strike on a maternity hospital in Mariupol; three people reportedly died on the spot, while a woman whose pelvis was crushed by debris died four days later after delivering a stillborn baby. Russian officials asserted that the hospital was being used as a base by the Ukrainian military, that the images of the bombing were faked, and that a pregnant woman seen being evacuated from the building with cuts on her face, Instagram beauty blogger Marianna Podgurskaya, was a crisis actor who played two different pregnant women in the photos of the bombing’s aftermath.

Bizarrely, a few days ago the pro-Kremlin propaganda machine made yet another attempt to debunk the hospital attack by circulating an interview with Podgurskaya, who apparently ended up either in Russia or in separatist-occupied Donetsk after her rescue. Whether or not the interview was coerced, it left no doubt, at the very least, that she was a real patient, not a plant. What’s more, Podgurskaya’s only claim that substantively contradicted the standard accounts of the bombing was that she didn’t hear an airplane before the hospital was hit and was told by staff that there had been no airstrike. (In fact, news reports alternately blamed the hit on an airstrike and on rocket shelling—a dubious improvement.) Some pro-Putin Twitter accounts, including that of right-wing American journalist A.J. Delgado, seized on Podgurskaya’s supposed mention of the maternity hospital being taken over by Ukrainian soldiers; but at that point in the interview, Podgurskaya was talking about a different hospital where she had initially intended to go.

There were some disturbing reports from the other side as well. In late March, an apparently authentic video showed wounded captured Russian soldiers being slapped and kicked by Ukrainian soldiers and other Russian prisoners being shot in the legs. While some Ukrainian officers said the photos were staged, a senior adviser to president Volodymyr Zelensky said the incident was “unacceptable” if real and that it would be investigated. Pro-Russia commentators such as Fox News’s Tucker Carlson were also quick to seize on a report of a Ukrainian frontline medic, Gennady Druzenko, saying in a television interview that he had ordered his staff to castrate wounded Russian soldiers because they were “cockroaches, not people.” Druzenko later apologized, saying that no such orders were ever given and that he had spoken in an emotional moment, and no one has even alleged that any Russian prisoners have been in fact sexually mutilated. (That is, unless you scour Twitter long enough to stumble on a Russian propagandist asserting that someone with a “reliable #Telegram channel” claims to have seen video and photo evidence of three such acts.)

ALL OF THAT, however, pales before the hair-raising reports from the liberated Kyiv suburbs. The photos and videos of dead people lying in the road, or slumped at the wheels of the cars where they were shot. The mass graves, reportedly containing more than 400 bodies. Victims of mass executions, some with tied hands, strewn in the yard of an office building amidst garbage. A man’s half-naked bloodied body dumped into a cistern. More bodies in the basements of homes. An old woman in the front yard of her house showing journalists the body of her middle-aged daughter who’d been gunned down from a passing Russian tank, the unburied dead woman’s legs sticking out from under plastic sheeting after the boards that had covered the body were lifted to allow visiting officials to examine it. Accounts of four weeks of living hell that included rape at gunpoint, followed by beatings the marks of which could still be seen on the victim. It makes for almost unbearable reading and viewing. A man shot dead for being out past the 3 p.m. curfew because he was running to the hospital after his wife had gone into labor. A 60-year-old veteran of the Soviet war in Afghanistan, shot dead because he refused to vacate his home.

Confronted with all this horror, what’s a pro-Russia spinner to do? Well, if you’re Glenn Greenwald, you lament the media’s uncritical use of “horrifying yet context-and-evidence-free photos and videos posted by Ukrainian officials” and praise the New York Times for at least acknowledging that these images and claims were not independently verified. Then you ignore the Times’s (and other media’s) subsequent firsthand coverage of the atrocities (and try to shift the focus to Hunter Biden’s laptop).

Or, in the case of independent reporter Michael Tracey, who has plunged headfirst into Ukraine Derangement Syndrome, you devote your Twitter feed entirely to tut-tutting at “emotional outbursts in reaction to the Ukraine government’s deliberately-crafted war propaganda,” deploring “attempt[s] to cajole US/NATO military intervention” with claims of genocide, and berating the Western media for credulously accepting the Ukrainian government’s claims.

While Tracey has demurred from actual claims that the massacres in the Kyiv suburbs were fake news or a false flag operation, he has avoided any comment whatsoever on media reports independently confirming the atrocities.

Meanwhile, more brazen pro-Russian Twitter has recycled and amplified the claims of Russian officials that the massacres are either a hoax with “crisis actors” playing corpses or the work of Azov Regiment “Nazis” who entered Bucha a day or two after the Russian forces left. These lurid fantasies, which would hardly merit rebuttal in a sane world, have been thoroughly debunked by the Bellingcat investigative group, which has pointed out, among other things, that the first photos of dead bodies were made before the arrival of Ukrainian troops. Tim Judah and Oliver Carroll, who reported on location for the Economist, have also confirmed that the bodies’ state of decomposition indicates that they had been around for several days. It is also worth noting that satellite images showing newly dug mass graves were taken on March 31.

Finally, as Human Rights Watch has pointed out, the grisly discoveries match the accounts given by locals—accounts that are all the more credible since they do not make blanket claims about Russian evil. Residents have said that many Russian soldiers were decent to them at first until they started turning bitter about military losses and their comrades’ deaths, or until regular Russian troops were rotated out and replaced with fighters from the notoriously thuggish separatist militias of the Donetsk and Luhansk “republics.”

The ”Azov Nazis done it” excuse certainly doesn’t explain one of the most shocking discoveries in the aftermath of the Russians’ departure. Olga Sukhenko, the mayor of Motyzhyn, a village near Kyiv, was kidnapped by Russian troops with her husband and son late last month; her abduction was first reported on March 26. On April 3, all three were found dead in a shallow grave, killed with gunshots.

This stuff really is straight out of the Nazi playbook. No wonder one elderly woman in Bucha, who had lived through the German occupation as a child, referred to the Russian occupiers as nimtsy, or Germans, asking with acid scorn, “What else would you call them?”

NO ONE WOULD DENY that wartime atrocities have historically been weaponized for propaganda—at least since ideals of civilized and honorable conduct of war arose and public opinion came to be all important. Nor is there any doubt that such atrocities have sometimes been exaggerated with the purpose, and effect, of inflaming passions. Reports of German atrocities in Belgium during World War I in the French and English press, for example, included tales of babies being bayonetted, children having their arms chopped off while clinging to their mothers’ skirts, women (including nuns) having their breasts hacked away, farmers being crucified, and priests and nuns being tied to church bells and smashed to death by bell-ringing. Later inquiries revealed that all these horrors were fictitious—though some modern historians note that the subsequent rush to dismiss all claims of German brutality during World War I as fiction resulted in some very real abuses, from widespread use of forced labor to mass executions in towns and villages believed to harbor snipers, being swept under the rug. Later, this skepticism also contributed toward disbelief in very real Nazi atrocities during World War II.

It would certainly be unwise to trust every Ukrainian account of atrocities completely. Some of the more grotesque, and so far uncorroborated, allegations—for instance, that Russian soldiers shot some women and girls in Bucha and then drove tanks back and forth over their bodies—should be taken with a grain of salt. But reasonable skepticism should not become denialism. And it is worth recalling that, while Ukraine has made claims that later turned out to be false—for instance, about the heroic deaths of the Snake Island Ukrainian guards of “Russian warship, go fuck yourself” fame—it is Russia that has an extensive record of “fake news” about Ukrainian atrocities, such as the lurid claim on Russian television in 2014 that an insurgent’s 3-year-old son in Slovyansk was crucified on a billboard in front of a large crowd.

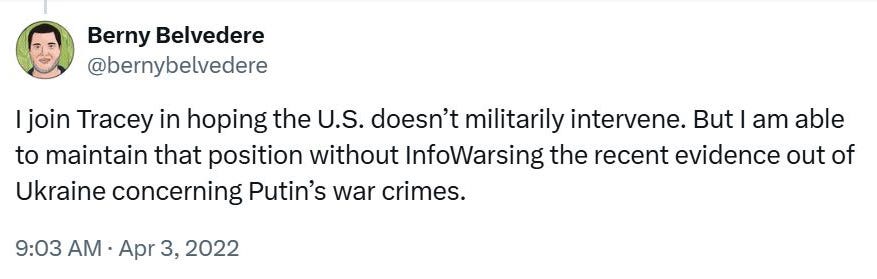

It also true that justified outrage over the slaughter and torture in the Kyiv suburbs—likely to be magnified when we learn the extent of Russian atrocities in other occupied towns and cities—should not push the United States into an ill-considered war. But the case against military escalation does not require denialism. As Arc Digital editor Berny Belvedere put it:

On the other hand, rejecting direct military intervention does not preclude more humanitarian and military aid to Ukraine, harsher sanctions against Russia, and a more realistic understanding of why calls for Ukrainian concessions in negotiations with Russia may be unworkable. Diplomacy must continue, but expecting Zelensky to sit down with the Butcher of Bucha at this point is insulting.

A CAUTIONARY TALE to close with: One of the journalists especially willing to believe in German atrocities in World War I was Walter Duranty. But eventually, he set out to investigate those reports and found, as a colleague recounted, that “none of the rumours of wanton killings and torture could be verified.”

Four years after the end of WWI, Duranty became the New York Times’s bureau chief in Moscow, a post in which he served for fourteen years. He won a Pulitzer Prize—and undying infamy as a denier of the Holodomor, Stalin’s terror-famine of 1932-33.

Don’t be like Walter Duranty—either in his World War I incarnation or his Stalin-era one.