'The Card Counter' Review

Plus: Can Nicole Kidman entice viewers back into theaters?

The Card Counter Review (Theaters)

The Card Counter isn’t about cards or counting them so much as it is about debts we count—of the monetary and psychic and spiritual variety—and whether or not they can be repaid.

Monetary debts are the easiest to incur but among the trickiest to extricate ourselves from, as William Tell (Oscar Isaac) happily explains when La Linda (Tiffany Haddish) offers to stake him as he makes his way around the poker circuit. Sure, La Linda and her sort might put up the money required to enter Tell into these tourneys. If he comes out ahead, she and he split the pot. But if he loses before making the cut—that is, if his chips dwindle to zero before lasting long enough in a tournament to cash out—the entry fee counts against future winnings.

Given the fact that only a small percentage of folks end up making the cut, and given the fact that these entry fees aren’t small—$1,000, $5,000, $10,000 a pop—these debts can add up real quick. Just like any other debt. Just like the college debt that dropout Kirk with a C, “Cirk” (Tye Sheridan), has accrued. Cirk is the product of a broken home: His mom has fled his abusive dad, a guard at Abu Ghraib who served with Tell before putting a gun in his mouth and pulling the trigger.

It is at Abu Ghraib, site of America’s most indelible stains from the Global War on Terror, that the other variety of debt is incurred. A moral debt. A spiritual debt. The sort of debt that can’t be paid off with time (Tell did eight-and-a-half years in Fort Leavenworth) or money (when Tell accepts La Linda’s offer, he does so in the hopes of being able to pay off Cirk’s loans, a psychic transference that from the start is doomed to failure). The sort of debt that awakes its holder with a start in the middle of the night, stirred from a reverse-fisheye-lens dream shot with a manic, sensory-barraging intensity by writer/director Paul Schrader.

That intensity comes infrequently and it is destabilizing to Tell. Hence his falling into the soothing numbness of gaming, of cards. The odds of poker and blackjack are clearly stated; anyone with a mind for math can make them work to his advantage. And the game of poker itself is both an example of fate and a deflection of it: the cards in a game of Texas Hold ’Em will fall however they will fall after they’ve been shuffled. The flop and the turn and the river are inexorable, like any train on any track. But they are still hidden to us, the odds we have to guide us just a guess, nothing more. We have free will in how we bet and how we scare people out of pots. We are fated to receive what we receive. The trick is accepting that which we cannot change and avoiding remonstrating to the heavens when fate trips us up.

“There is indeed an almost Zen-like state that takes place in poker, as the hours slip by and the game reaches a comfortable rhythm and the light changes in cardrooms and outside the windows of riverboats,” Larry W. Phillips writes in Zen and the Art of Poker. “It is similar to the state of people who are in the thrall of some other activity—one that, for the moment, dominates them and justifies their existence.”

Abu Ghraib and its depravities came to dominate Tell; the cards of the titular card counter are a sort of penance, the secular equivalent of counting rosary beads while asking forgiveness for his sins. One thing Schrader captures perfectly is the tactile nature of poker, as opposed to most other forms of casino gambling. The riffling of the heavy clay chips—the act of separating them, bringing them back together, shuffling them, and the pleasing click they make as they reassemble—is almost totemic, the act of feeling them in your hand as your mind separates from your eye and, yes, your hands, floating off, waiting to snap back into place when an opponent makes a mistake you can take advantage of.

One can’t say enough about Isaac’s performance in this movie, alternating as it does between icy marble and cracking flesh. During one monologue about the horrors he participated in, Schrader pushes in slowly until Isaac’s face takes up the full frame; the controlled agony he portrays is subtly devastating. Haddish is rawer than Isaac but in her rawness there’s a sort of vulnerability that sands down her character’s hucksterish qualities. And Sheridan’s just about perfect as the white-trash Cirk, a role that doesn’t necessarily demand much but to which he gives a great deal.

The Card Counter is one of the best movies I’ve seen this year and one that deserves your rapt attention. Please don’t wait to see this at home where you’re distracted by your phone or you’re tempted to live-tweet it: Go see it on a big screen that demands your focus and dominates your vision.

Make sure to check out my interview with Rod Lurie—director of The Outpost, The Contender, and The Last Castle, among other projects—on The Bulwark Goes to Hollywood this week. We talked about how he planned on breaking into the business following his stint as an officer in the Army and some of the perils of moving from the world of film criticism into the world of filmmaking. The story he tells about meeting Bill Paxton for the first time has to be heard to be believed; it’s every film critic’s nightmare brought to life.

And if you enjoy that show and this newsletter, consider chipping in to help keep this little enterprise sustainable; I’d surely appreciate it.

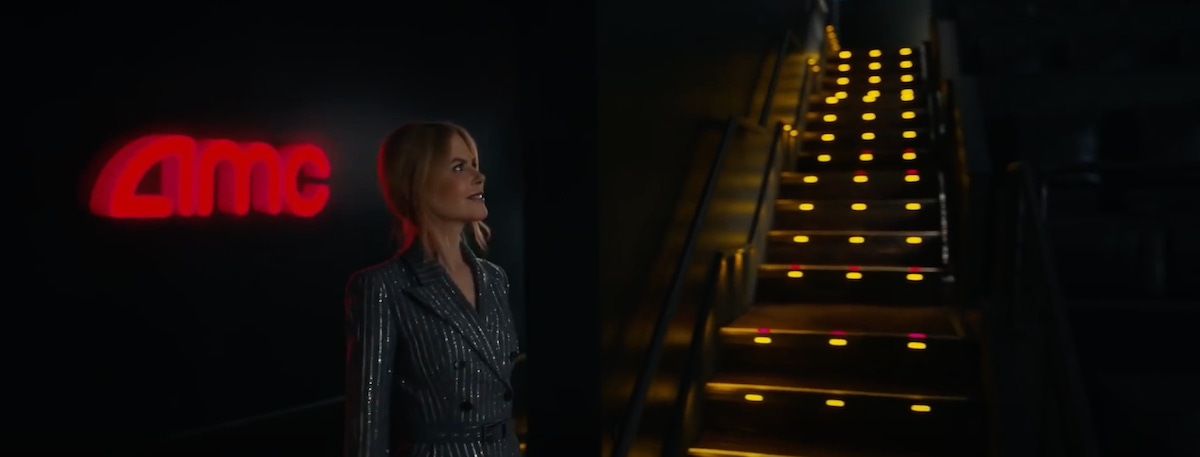

AMC’s Ad Campaign Is Admirable, But Mistaken

AMC is flush with cash because they’ve been saved by the redditors and turned into a meme stock, meaning that AMC can do things like pay down some of its debt or pick up valuable properties in big cities that still fill seats. They can also pay Nicole Kidman God only knows how much to do some gauzy spots reminding people of “the magic of the movie theater.”

Of all their expenditures, it’s the last that’s the most public-facing. It’s also, probably, the biggest waste of money.

Here, watch the ad for yourself so you can see what I mean:

“We come to this place for magic,” Kidman, beaming at an AMC sign, says. “We come to AMC Theatres to laugh, to cry, to care. Because we need that, all of us. That indescribable feeling we get when the lights begin to dim—and we go somewhere we’ve never been before.”

And then images from movies flash on the screen: Jurassic World, Wonder Woman, Creed, La La Land, movies designed to appeal to a wide variety of demographics and age ranges. Beautiful pictures on a huge screen with a statuesque actress grinning madly at the joyous wonder of it all. The glamor, I can barely stand it!

But it doesn’t really address the issues most people have with movie theaters or the theatrical experience. When I talk to people who are hesitant about returning to theaters, yes, some of them talk about their TV or their sound system. You’re never going to convince people that their OLED and their soundbar isn’t good enough; they’re both emotionally and financially invested in their home theater.

And you’re probably not going to convince people that seeing movies with other people is a grand connective experience given that most people’s experience of other people in a movie theater is that of cell phone use and annoyingly loud talking. Yes, it’s great to be alone together in the dark, but alone is better than together, when push comes to shove.

No, when I talk to people about staying away from theaters, they repeatedly bring up one of two points: It’s not safe because of COVID and/or there’s nothing new worth seeing in theaters anyway, so why would I go?

Unfortunately, there’s only so much AMC can do via advertising to alleviate the first concern, since advertising about it at all is only going to reinforce the fact that we’re in a deadly pandemic and moviegoing is seen as an unnecessary luxury in such situations. Yes, film critics and film lovers in general could be doing a better job of reminding people that theaters are safe, that vaccines are effective, and that watching a movie in a giant room with other people all facing the same way is not at all an activity conducive to spreading COVID.

And theaters have very little control over the product delivered by studios. They can’t force Paramount to put Top Gun Maverick back on the schedule. They can’t force Warner Bros. to give them a couple of exclusive weeks of Dune or The Matrix Resurrections. Theaters have an exclusive blockbuster a month from now to the end of the year, on top of the awards-season and arthouse fare that starts rolling out in October. They’re going to have to hope that’s enough to rekindle the moviegoing habit.

In short: I love Nicole Kidman. But I’m not sure having the star of Nine Perfect Strangers (Hulu), The Prom (Netflix), The Undoing (HBO Max), and Big Little Lies (HBO) extol the power of theaters is the best way to get people back into them.

Assigned Viewing: First Reformed (Showtime)

I remain somewhat flummoxed by this movie, insofar as it strikes me as very similar to Taxi Driver—another movie about a lonely man who fills the romantic void in his life by submitting to narcissistic extremism—but I get the sense we are supposed to side with Reverend Toller (Ethan Hawke) as he slides into extremism, whereas Travis Bickle is clearly meant as a cautionary tale.

I’ve written about this at length elsewhere so I won’t recapitulate it here; suffice to say that it’s interesting to watch Taxi Driver (which was written by Paul Schrader), First Reformed (written and directed by Paul Schrader), and The Card Counter (also written and directed by Paul Schrader) in relative proximity to one another. God’s lonely men and the transcendental style, man. Good stuff.

Re: First Reformed

I loved it. I dunno I saw it less of a continuation of Taxi Driver and more of a wrestling match between religion and spiritual. But, hey, that’s me as a man of faith wrestling with the shallowness of Christian culture.

Re: The AMC ad do you remember the trailer for the Star Wars Special Edition?

Watching the X-Wing explode from the tiny TV and splashing across the giant movie screen was the best example of how theaters > home.

https://youtu.be/eRgsMKu8oNA

The AMC video should have opened with Nicole Kidman walking past some dupe watching Dunkirk on a iPad and just having utter disgust on her face.

I don't know what this says about me, but I try to see something every week and probably twice this weekend. Also, First Reformed is amazing so thank you for inspiring me to rewatch it.