The Case for an Imperfect Solution in Afghanistan

Ridding the country of the Taliban doesn’t appear to be a reasonable objective. Dividing the country might be the next best option.

Among the more ambitious foreign policy objectives of the Trump administration was its pursuit of a decisive resolution to the war in Afghanistan. Despite the persistence of insurgent attacks since the signing of the preliminary peace deal on February 29, 2020, optimism for a negotiated peace settlement with the Taliban has prevailed among a significant number of Afghan and international political and military leaders, Afghanistan analysts and scholars, and the Afghan population. This optimism has been bolstered by the December 2 signing of a procedures and modalities agreement in Qatar.

This optimism is driven by a narrative in which the Taliban are characterized as war-weary, coming to grips with the dim prospects of achieving a military victory, and in which this plummeting morale is credited with softening the Taliban’s stance, bringing them around to a reduction in violence in favor of a negotiated political solution. Much has been made of the Taliban’s willingness to come to the table, or “come under the tent” (to invoke a turn of phrase suggested to me in conversation with a former vice-president of Afghanistan). This development has been highlighted as a sign of progress, and heralded as a breakthrough credited to the Trump administration, carrying with it the implication that the United States has brought a diminished and demoralized negotiating partner to the table by means of an effective military campaign, and is in a position of strength. In line with this narrative, the ongoing Taliban terror attacks targeting Afghan civilians and military personnel across Afghanistan are chalked up to efforts by the Taliban to gain leverage at the negotiating table, and the continued presence of Operation Resolute Support (the successor coalition to ISAF) forces is justified by citing the need to maintain leverage with a military presence.

Though a receptive audience has embraced and buoyed this narrative, it nonetheless presents inconsistencies and non sequiturs.

Indeed, the Trump administration did bring the Taliban to the table, and this development has been framed as an achievement and lauded as a sign of progress despite the fact that this opportunity for negotiations materialized solely because the Trump administration acceded to the insurgent group’s demands for direct negotiations with the United States that exclude the government of Afghanistan. Previous administrations had been unwilling to accede to these demands, but the Trump administration changed course, apparently to facilitate the expeditious withdrawal of troops.

It has been suggested that optimism on the part of the Taliban is unwarranted given the scant likelihood of their achieving a decisive military victory while Resolute Support forces remain on the ground. In August 2017, Secretary of State Rex Tillerson put it this way: “This entire effort is intended to put pressure on the Taliban to have the Taliban understand: You will not win a battlefield victory. We may not win one, but neither will you.” This military impasse has been reverse-engineered into a motive for the Taliban to be eager to reach a political resolution through dialogue, with the implication being that the Taliban and the U.S. are equally invested in negotiations as a means to push past the stalemate on the battlefield.

However, there is no evidence to suggest that the Taliban have come to the table in search of a political solution as a result of having grown weary of the conflict. The Taliban now control more territory than at any time since 2001, and they appear to be energized by their battlefield gains, as well as the ongoing withdrawal of U.S. troops: “The 17-year-long struggle and sacrifices of thousands of our people finally yielded fruit,” proclaimed a senior Taliban commander in Helmand province. “We proved it to the entire world that we defeated the self-proclaimed world’s lone superpower.” Any successes extracting concessions from the Taliban will be hard-won: “The Taliban,” a former Taliban government minister said, “has the upper hand in the situation, and we know how to mobilize this situation in the Taliban's favor.”

It should be noted that a military victory is not imperative for the Taliban; that is, a military victory is not a necessary condition for the Taliban to prevail in this conflict. The insurgency serves as an end in itself given that the Taliban are operating on home turf. The Taliban do not need to win; they just need to disrupt for as long as it takes, that is, until coalition forces head home. The Taliban like to say of the coalition: “They’ve got the watches, but we’ve got the time.” They are playing the long game: “For generations we have fought this war, we are not scared, we are fresh and we will continue this war until our last breath,” a senior Taliban commander told AFP. In this context, it makes little sense to think of the ongoing insurgent attacks as a ploy to gain leverage. The Taliban already have as much leverage as they need; they have time on their side. The ongoing violence appears to be a flex.

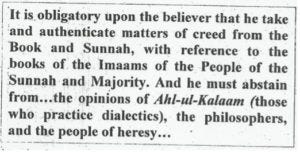

We will continue to underestimate the resolve of the Taliban if we fail to recognize that they are fighting what they consider to be a holy war. This is not a political struggle; the Taliban are pursuing religious objectives in the political sphere. We should not expect the Taliban to compromise on their religious beliefs. Compromise is heresy; absolute faith is requisite:

Taliban Periodical (Disinterred in Afghanistan): Mawlawi Jan Muhammad Madani, “The Root of Tawheed and Basis of Acceptable Belief,” The Islamic Emirate, November/December 2000, p.33 There is no reason to expect that the Taliban will ever agree to form a coalition with the U.S.-backed Afghan government, which the insurgent group considers to be a “puppet” of the invading “infidel” forces. While the Taliban have demonstrated their willingness to engage in talks or consultations with a cross section of Afghan society, including Afghan government officials, there should be no expectation that such talks will yield a binding agreement between the Taliban and the government of Afghanistan in its current incarnation. The December 2 signing of the procedures and modalities agreement following meetings in Qatar has been heralded as a breakthrough; however, the agreement “was reached without the inclusion of the Afghan government’s official name” at the behest of Taliban negotiators. The Taliban have indicated that their objective is to take the reins:

“The current Afghan system is totally corrupt and incapable,” began one of the senior members of the Taliban's negotiating team, suggesting that forming a coalition with the “sinking ship” of President Ashraf Ghani's government would “drown the Taliban as well.”

“Now it's the Taliban's turn,” he said. “Hand over the Afghan regime to the Taliban for three to five years. The Taliban will work with the international community, especially the U.S. We will prove that as the Taliban was a hard enemy, in the future we will be a solid and trustworthy partner.” The Taliban’s commitment to concessions brokered through a peace deal also becomes increasingly tenuous as the organization optimizes existing revenue streams and taps into new ones:

The Taliban's burgeoning financial might could make the militant group immune to pressure from the international community as it negotiates a role in postwar Afghanistan, according to a confidential report commissioned by NATO and obtained by RFE/RL.

The Taliban “has achieved, or is close to achieving, financial and military independence,” a scenario that could allow the Sunni extremist group to renege on key commitments it has made under a U.S.-brokered peace plan aimed at ending the 19-year war, the report warns. Similarly, the use of military force falls short of offering a pathway to enduring peace and stability. There is no decisive military victory in sight for the coalition, and the Taliban have been emboldened by the apparent popular support in the United States for withdrawal of the troops. The spokesman of the Taliban political office in Qatar, Suhail Shaheen, welcomed the remarks made by the president, along with the warm reception of said remarks, at a rally in Minneapolis on October 10, 2019:

Shaheen said . . . that “Trump once again promised to withdraw forces from Afghanistan" and added that this “means that ending the occupation of Afghanistan is the American people's choice.”

Trump told Thursday's rally that American soldiers have been in Afghanistan almost 19 years and that “it's time to bring them home.”

He got a standing ovation. Though the February 2020 peace deal specifies that all coalition forces will leave Afghanistan by May 2021, the announcement on November 17 by President Trump’s last acting secretary of defense, Chris Miller, that the United States would reduce the number of troops from 4,500 to 2,500 by January 15 was met with consternation given that the announcement did not address stipulations regarding conditions on the ground. Indeed, the November 11 appointment of Col. Douglas Macgregor as a senior adviser to Miller suggested that the impending drawdown would not be conditions-based:

Macgregor’s appearance in Tampa is now a part of Army legend. The U.S. military can take Baghdad with 15,000 troops, Macgregor announced to the room of uniformed experts. The statement stunned Franks, as did Macgregor’s advice on “Phase IV” (postwar) operations—which had not been mentioned in his briefing. Why wasn’t it there? Macgregor was asked. “The reason it’s not there,” Macgregor said, “is because we’re not going to need it. We’re going to turn the governing of Iraq over to the Iraqis, then we’re going to get out.”

It is expected that President Biden will favor following through with Trump’s planned withdrawal of troops, maintaining only a light footprint to support counterterrorism measures. Meanwhile, the Taliban have indicated that, for their part, the February 29 agreement is rendered null and void if any troops remain on the ground.

A decisive resolution to the conflict that will serve to uphold the gains of the past nineteen years will require a creative solution. In 2011, former deputy national security advisor Robert Blackwill argued for, essentially, ceding the Taliban strongholds in the south and east of the country to focus on strengthening the non-Taliban-controlled north and west, including Kabul. Considering how little the obstacles to victory in Afghanistan have changed since Blackwill’s original proposal, it could be time to revisit the possibility. Unlike the proposed formation of a coalition government that includes both the Afghan government and the Taliban, the creation of a semi-autonomous Taliban region could allow for a viable path forward. A bespoke model for Taliban autonomy could be crafted through an Afghan-led process involving the examination of case studies such as Zanzibar, a semi-autonomous region, and Hong Kong, a special administrative region, as a backdrop to an articulation of the “philosophical, political, cultural, [and] legal” modalities of Taliban autonomy. Afghan national forces, and whatever coalition forces that remain, could focus on a defense, peacekeeping, and reconstruction mission in the non-Taliban sections of the country.

Such a resolution would not provide the tidy, decisive victory that has eluded the coalition for two decades, but it could allow the United States and its allies to finally resolve the Afghanistan issue and focus on other challenges.

[Editor's note, Jan. 26, 2020, 9:05 AM: This article has been updated to specify that the proposal for forming an autonomous region would be Afghan-led.]