The CHIPS Act Is Popular, Bipartisan, and a Bad Idea

Instead of trying to recreate the Taiwanese semiconductor industry, we should be doubling down on defending it.

With large, bipartisan majorities in both chambers, Congress just passed the Creating Helpful Incentives to Produce Semiconductors for America Act, more commonly known as the CHIPS Act, which now awaits President Biden’s signature. The bill, which allocates $54 billion in subsidies to the American semiconductor industry, is a product of a concern that world’s semiconductor production is over-reliant on Taiwanese and Chinese firms, which could mean Chinese market domination if the People’s Republic decides to annex Taiwan. Those fears are based in reality, and the CHIPS Act makes them likelier to become reality.

Taiwan is the world’s largest producer of semiconductors. Its companies account for 66 percent of the market, produce almost half of the world’s semiconductors, and dominate the market for high-end semiconductors even more. Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Company (TSMC) is one of only two companies capable of producing cutting-edge 5-nanometer chips and is scheduled to produce 3-nanometer chips later this year. Given that the next two largest producers of semiconductors are South Korea, a country subject to Chinese bullying and intimidation and North Korean threats, and China itself, it makes sense that Congress would worry about where we (and the rest of the world) are getting our key high-tech components. But the solution is to double down on Taiwan, not to decouple from it.

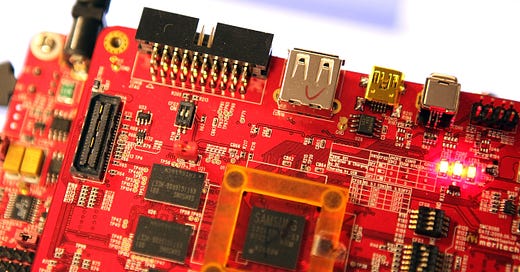

When we talk about semiconductors, we’re not really talking about the Periodic Table—at least, not in this context. The issue is what we use semiconductors to make: microchips and nanochips, the tiny machines at the heart of every computer, in every configuration, pretty much anywhere, from an iPhone to a remote control to air traffic control to guided munitions to power plants to the Large Hadron Collider. If China becomes the monopoly supplier of semiconductors, and therefore the chips made from them, it will gain coercive influence on the rest of the world, including the United States. This is not to say that patiently developing our own capabilities or accepting Chinese coercion are the only possible outcomes. Eventually, the monopoly would be broken, but how, when, and by whom would all be open questions.

Microchips and nanochips also matter a great deal to China domestically. Since the 1980s, the Communist Party has legitimized itself through economic growth. But that growth is gone, and Chinese economic prospects are dim, risking the party’s hold onto power. The current ruling class believes that it can regenerate growth by becoming the world’s technological leader, and, for this, semiconductors are an indispensable industry.

The CHIPS Act tries to avoid the risk of a Chinese monopoly on chips by jump-starting the American industry with $54 billion (which, for comparison, is less than what TSMC alone earned in revenue in 2022). This move will be counter-productive in the short-term and possibly the long-term. First, it sends a signal to China that the United States is not serious about defending Taiwan. The United States has long maintained a policy of “strategic ambiguity” about whether it would go to war to defend Taiwan. The CHIPS Act announces to the Chinese leadership (and to the Taiwanese, for that matter) that the United States is leaning against going to war to defend Taiwan, so it’s investing in alternative sources for chips. If the United States were 100 percent committed to defending the island democracy, why would it be looking for economic alternatives? Today, most analysts inside and outside of China believe that the People’s Liberation Army won’t have the capability for a cross-strait invasion until about 2027, but the more the United States signals that it’s not committed to opposing such an invasion, the easier it is for the People’s Liberation Army to imagine that they’d be fighting the Taiwanese alone. That makes war more, not less, likely.

The same logic applies to the rest of the world and forms the second, longer-term problem with the CHIPS Act. The less the world relies on the Taiwanese chip supply, the less it will care about the fate of that nation. Taiwan already lacks normal diplomatic relations with countries around the world because China often bullies other countries into downgrading their relations with Taipei. As a consequence, Taiwan struggles to forge liberal international trade relations. Reducing the world’s commercial interest in Taiwan will correspondingly reduce the world’s commitment to defend Taiwan against a much larger enemy.

The third problem with the bill is that it might actually work. Given that the chip industry makes up more than 10 percent of Taiwan’s GDP, establishing a serious domestic competitor in the United States would mean reducing Taiwan’s exports, harming their economy, and in turn making it harder for them to afford the military they need to deter or defeat a Chinese invasion. Once again, the CHIPS Act would make it more, not less, likely that China will attempt to invade Taiwan—and that it will succeed.

But the CHIPS Act is unlikely to accomplish its goal of boosting American industrial capacity enough in the short- and medium-term to compete with Taiwan, which boasts a 35-year head start in both know-how and infrastructure. As a result of the CHIPS Act, the Taiwanese will have new reasons not to share their sophistication with American manufacturers just at the time that we’ll most need their help. The private sector in Taiwan will have a financial interest in guarding itself jealously, and the government has a strategic interest in maintaining foreign reliance on its country’s supply.

Yet while the policy might not get us in time to be self-sufficient in chips production, it could fool us to believe that we are. We will never know if we can live without the supply of a good until we have to live without it. Perhaps the most disastrous possible outcome of the CHIPS Act would be for the United States—its people and its government—to come to believe unrealistically that the country didn’t need the Taiwanese supply, only to rediscover their dependence after a Chinese occupation of Taiwan. Having deluded itself about its self-reliance, the country would be left only with the options of allowing China to swallow Taiwan and its semiconductors or going to war to liberate Taiwan.

If Congress wants to ensure that the United States has a protected source of affordable, state-of-the-art chips, it should do everything it can to ensure that the already-thriving industry in Taiwan that has powered the computer revolution for decades remains safe and free. The amount of money that Congress has authorized to try to copy TSMC could go a long way toward defending Taiwan. It could, for example, buy 25 more destroyers and train our sailors better so they stop crashing the ships. Or to quote Asia expert Dan Blumenthal, instead of a CHIPS Act, Congress should have passed a SHIPS Act.