The Chokehold Killing: What the Stupid Left-Right Debate Obscures

First death, then distortions.

DANIEL PENNY, A 24-YEAR-OLD MARINE VETERAN, was charged last week with second-degree manslaughter in the fatal choking of Jordan Neely, a 30-year-old homeless man, during a confrontation on the New York subway on May 1. The case has split commentators and public opinion into camps that roughly align with the left and right—and the explosive rhetoric on both sides has obscured the facts of the case and overwhelmed our ability to reason about them calmly.

Without bothering to wait for the law to take its course, a number of Republican politicians have spoken out about the case. Donald Trump said that he believes Penny and his fellow passengers were in “great danger.” Other GOP presidential hopefuls have also rushed to praise Penny for protecting fellow passengers from a mentally disturbed violent criminal. Florida Governor Ron DeSantis hailed Penny as a “Good Samaritan” and promoted a link to a crowdfunding site that has so far raised $2.6 million for Penny’s legal defense. Nikki Haley, the former South Carolina governor, has called for Penny to be preemptively pardoned. Still other Republicans have called Penny a “hero.”

Meanwhile, some Democrats, including Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, were just as quick to declare that Neely was “murdered” or even, in the words of one state senator, “lynched.”

Right-wing and left-wing media have offered equally discordant narratives: Penny is either a hero who is being hounded by leftist activists and by a “woke” prosecutor for defending himself and others, or he is a murderer excused because the victim was a homeless, mentally ill black man who made people uncomfortable by complaining about being hungry.

The real facts of what Penny did and what happened to Neely in those fateful moments on the F train are still emerging and may never be fully known (despite a partial video). It’s a fact that Neely was acting erratically on the train, that Penny tackled him and put him in a chokehold while the two men struggled on the floor, and that two other male passengers helped pin Neely down.

It’s a fact that Penny’s chokehold killed Neely, as the medical examiner determined; his death has been deemed a homicide.

It’s a fact that Neely had an extensive history of mental illness, substance abuse, and arrests for violent behavior—most recently in 2021, when he randomly punched a 67-year-old woman leaving a subway station in the face, knocking her down and causing facial and head injuries.

It’s a fact that when outreach workers approached Neely on the subway in April, three weeks before his death, he urinated in front of them, prompting one of them to call the police; the team’s notes on the incident stated that Neely was “aggressive” and “could be a harm to others or himself if left untreated.”

It’s a fact that he had not assaulted anyone on the F train on the day of his death, though witnesses (including Juan Alberto Vasquez, the freelance journalist who filmed the widely viewed three-and-a-half-minute video) described his behavior as alarming. Indeed, the lead prosecutor at Penny’s arraignment acknowledged as much, saying, “Several witnesses observed Mr. Neely making threats and scaring passengers.”

Obviously, none of this means that Neely deserved to die, or even to be preemptively attacked. But Vasquez and the other passengers on the car thought Neely was being restrained, not killed. The chokehold has been widely used as a restraint technique not only in police work but in martial arts; however, in recent years, with rising concerns about police brutality, it has been increasingly viewed as potentially lethal in law enforcement, and some states and police departments have banned its use or restricted it to extreme cases in which deadly force is warranted. Even so, this hardly proves that Penny knowingly used deadly force. The choking may have been a tragic but accidental outcome, or Penny could have recklessly used excessive force. This is something that the Manhattan District Attorney’s office has now said is for a grand jury to decide—and then a trial jury if an indictment is returned.

FOR THE LIBERAL AND PROGRESSIVE politicians, pundits, and activists outraged by the fact that the man who put Neely in a fatal chokehold was released without charges after being questioned by the police—and that early police statements seemed slanted toward making Neely the bad guy, stressing his prior arrests for assault and his harassment of fellow passengers—this was self-evidently a story about a white, privileged killer being favored over a black, marginalized victim. In a New York Times piece called “Making People Uncomfortable Can Now Get You Killed,” Roxane Gay summed up the situation this way:

“I don’t have food, I don’t have a drink, I’m fed up,” Mr. Neely cried out. “I don’t mind going to jail and getting life in prison. I’m ready to die.” Was he making people uncomfortable? I’m sure he was. But his were the words of a man in pain. He did not physically harm anyone.

Gay didn’t seem to notice that the words she quoted could quite reasonably be taken to express an implicit threat: If you say that you’re prepared to get life in prison, it sounds a lot like “I’ll kill someone if I have to.” (Some early news reports also mentioned that Neely said he would “hurt anyone on the train”; however, those words are a paraphrase of a report from “police sources,” not a direct statement by an eyewitness. One witness later recounted to the New York Post even more threatening ranting by Neely—“I would kill a motherfucker”; it is worth noting, however, that she had strong feelings in Penny’s favor, which may have skewed her recollection.) Vasquez also says that after the rant, Neely threw down his jacket with enough force that one could hear the metal zipper hit the floor—and that he saw this act as a possible danger sign. If someone is using threatening language and gestures, you’re not required to wait until there is an actual physical assault to stop that person—although, again, the question of proportionality remains: Vasquez mentions that Neely stayed exactly where he was when he threw his jacket and did not move toward anyone around him, which helps explain Vasquez’s ambivalence about Neely’s intentions: while he did not see what happened immediately prior to Penny tackling Neely, he recalls being unsure if Neely was actually going to commit a violent act. But to describe subway riders’ reaction to Neely as mere “discomfort”—something that quite a few commentators did—is to minimize what sounds like well-founded fear.

Gay also concludes that “public life shared with terrified and/or entitled and/or angry and/or disaffected men is untenable”—referring to Penny and to several men who have fired guns, in a variety of recent incidents of sudden violence over petty arguments or imaginary threats (ones that strike me as quite dissimilar from the circumstances of Penny’s act). However, she doesn’t ask whether it’s tenable to share public space with a man whose inner demons may drive him to try to drag your child down the street (Neely had done that in 2015) or randomly punch you in the face.

For a number of progressive commentators, the answer seems to be yes. In the most bizarre iteration of this position, Emma Vigeland of the Majority Report, a left-wing YouTube show, told a story about being hit in the face on the subway by “a man who was having a mental health episode” and was flailing and elbowing people around him. While conceding that she was “a little scared,” Vigeland insisted that “the fact that this person is in pain” should be more important and deplored how “the politics of dehumanization privileges the bourgeois kind of concern of people’s . . . immediate discomfort” over “larger humanity and life.” One wonders how Vigeland would have reacted if, when she was herself being hit in the face on the subway, someone had shared such platitudes with her.

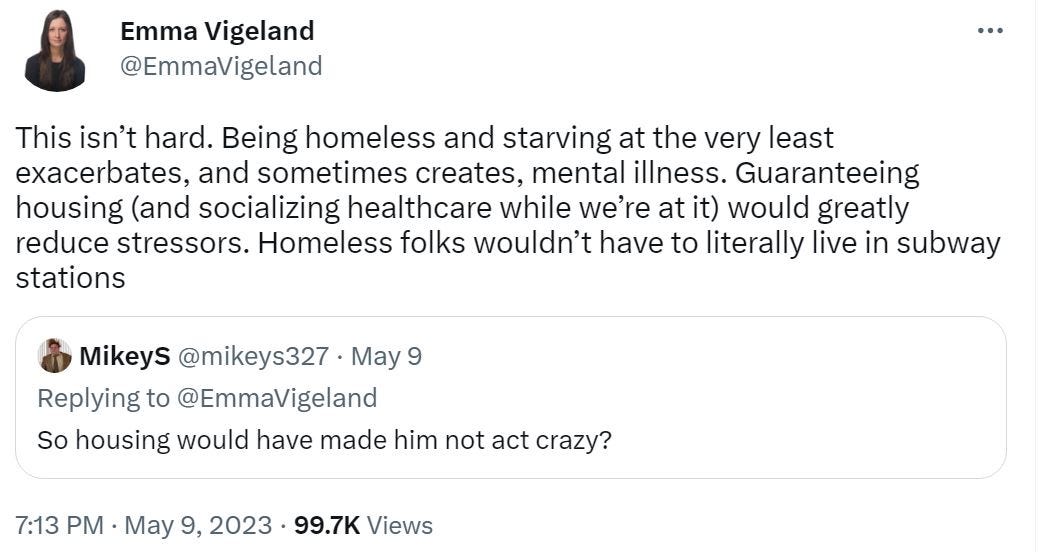

Vigeland has also echoed another common progressive argument: that homeless people suffering from mental health crises are primarily victims of homelessness and poverty.

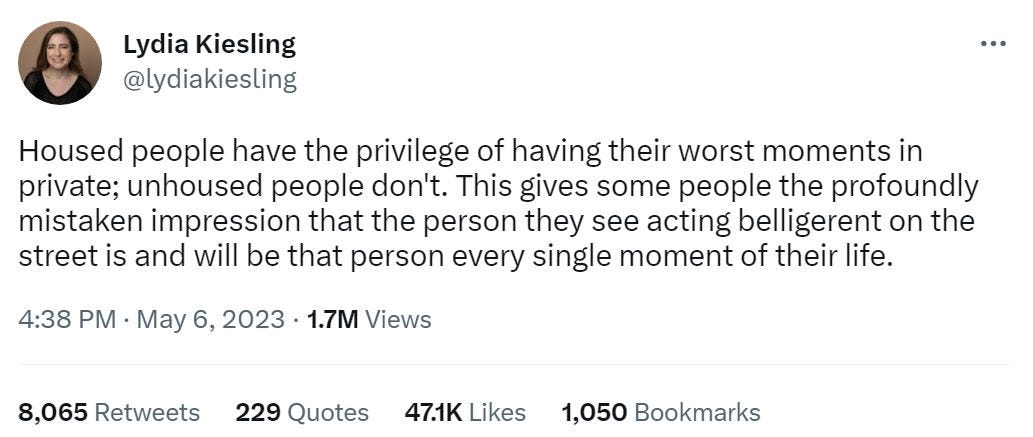

Novelist Lydia Kiesling touched on a similar theme in a viral tweet, asserting that “unhoused” people often seem more unhinged than others—and destined to remain that way—simply because they have no closed doors to hide their breakdowns behind:

While the attempt at imaginative sympathy is noble—and it’s certainly true that having a home affords a privacy that is simply not available for those who live their lives in shelters and on the streets—Kiesling’s and Vigeland’s tweets suggests a highly unrealistic view of mental illness and its connection with homelessness. The causality often seems to go in the other direction, with people losing jobs, housing, and support systems among family friends due to violence and paranoia.

While Neely had clearly needed help, he certainly needed more than housing and food. Last February, after pleading guilty to assault, he agreed to stay for fifteen months at a treatment facility where he would take psychiatric medication and stay off drugs. He even thanked the prosecutor for what she said was “a wonderful opportunity to turn things around.” Less than two weeks later, he left the facility and never came back. (There was an outstanding warrant for his arrest at the time of his death.) Many accounts in the liberal and progressive media of Neely’s life tended to downplay Neely’s record of violence while highlighting his history as a Michael Jackson impersonator. A piece in the New Yorker noted that he “had been arrested more than forty times, mostly for petty offenses, such as loitering and trespassing” but omitted the assaults and the attempted child abduction—thereby creating the false impression that Neely’s criminal offenses had amounted to existing while homeless. The article also mentioned the encounter with the outreach workers in April but not their assessment of Neely as aggressive and potentially dangerous to himself and others.

What’s more, while these accounts have often stressed the racial angle—the fact that Penny is white and Neely was black—virtually none has mentioned a fact that seems salient if we are to look at this incident through a racial prism. The second man who is seen in the video helping restrain Neely and pin his arms when he tries to struggle—and who also appears to reassure a concerned rider off-camera that Neely is all right—is black. Should he be regarded as accessory to murder, or even an accomplice to a lynching?

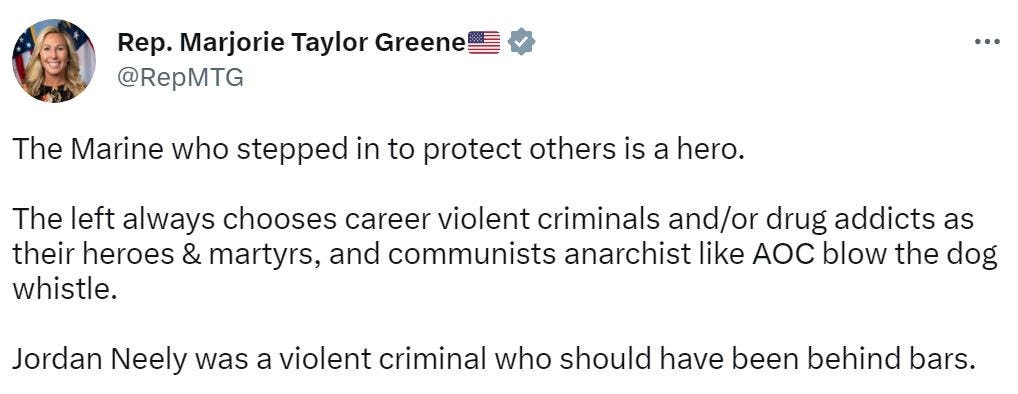

DESPITE CONSERVATIVES OFFERING SOME reasonable points about problems with progressive and liberal responses to Neely’s killing, there has also been plenty of noxious rhetoric on the right which, in turn, validates the worst of progressive stereotypes of conservatives—above all, the utter lack of humanity toward a man whose violence was the result of illness, not malice. Neely, diagnosed with schizophrenia, depression, and severe PTSD, had a genuinely tragic life: When he was 14, his mother was murdered by her boyfriend. Yet Daily Wire blogger Matt Walsh has described Neely as a “violent predator.” (He has also suggested, skewing the facts in the reverse direction from the New Yorker, that all or most of Neely’s forty-plus arrests were for violent assaults.)

Rep. Marjorie Taylor Greene, whose Twitter bio starts with “Christian,” had her own take:

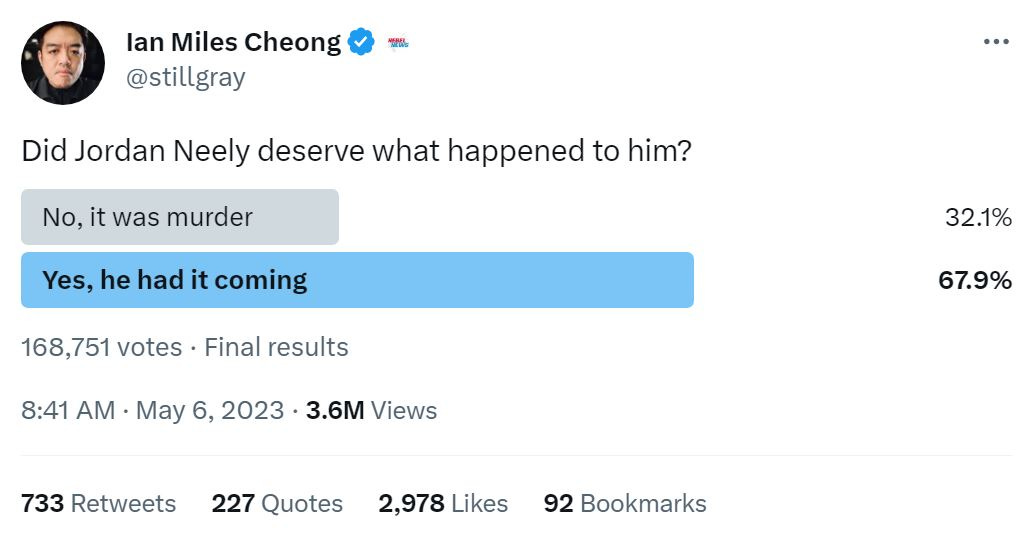

Ian Miles Cheong, the Malaysian blogger who has strong opinions on American cultural issues and nearly 600,000 Twitter followers, and who has been affiliated with a wide range of right-wing sites, including Human Events, the Daily Caller, and the Post-Millennial, outdid the rest with a truly vile poll:

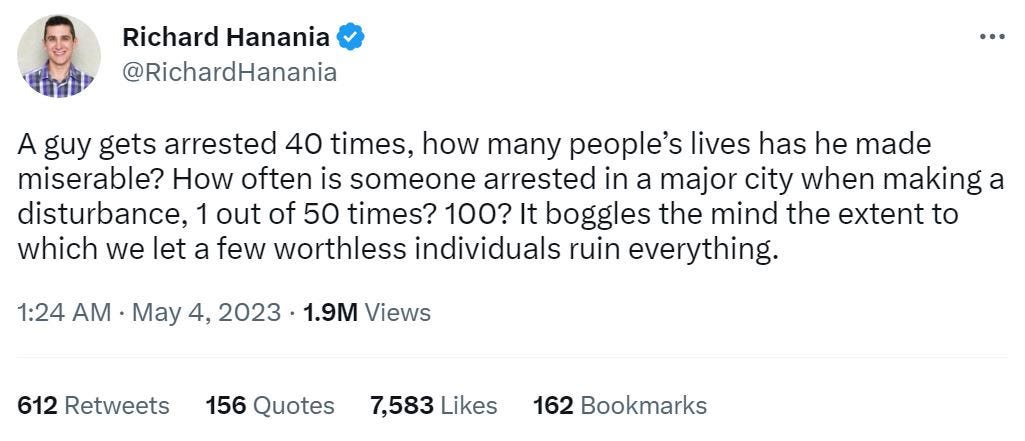

And then there was this from right-wing academic and troll Richard Hanania:

Meanwhile, on YouTube, right-wing comedian and commentator Steven Crowder weighed in with a monologue in which he asserted, twice, that you “forfeit your right to live” when you act as Neely did. Wait, so the death penalty is a proper punishment for creating the impression that you are about to commit an assault? (The “pre-crime” of assault, perhaps, to put things in Philip K. Dick’s terms?) Crowder hedged and noted that “I’m not saying that the man deserved to die, it’s a tragedy”—but, given his past crimes and the situation in which he put the people on that subway car, “Jordan Neely forfeited his right to live.” I’m not sure how to parse the logic, but the sentiment is loud and clear.

Such statements from a popular figure (Crowder has 5.86 million followers on YouTube) unquestionably have a coarsening and dehumanizing effect on the right, and they are admittedly uglier and morally worse than progressive and liberal attempts to give Neely a posthumous airbrushing. But beyond that, they also continue the vicious cycle of polarization. Many liberals and progressives repelled by the right-wing dehumanization of Jordan Neely will be likely to conflate it with any discussion of Neely’s violent record and threatening behavior on the train. We will get false and misleading narratives on the left, such as a Media Matters roundup of mostly ugly right-wing comments about Neely’s death which opens with this disingenuous summary written by the Media Matters staffers: “Neely was reportedly choked to death by former Marine Daniel Penny after allegedly yelling on the subway about having no food.” Sorry, Media Matters, but that’s right up there with claiming that January 6th rioter Ashli Babbitt was shot dead for protesting in an unauthorized area.

THIS CYCLE OF MISBEGOTTEN partisan discourse obscures very real dilemmas of how society should deal with severe mental illness—especially when it is linked to aggressive, violent, dangerous behavior.

It is easy to agree with Manhattan District Attorney Alvin L. Bragg (whom the New York Post describes as being “on Team Crime”) when he says that “Jordan Neely should still be alive today.” But it is equally true that Neely should not have been harassing and threatening subway riders—and should not have been homeless, hungry, and in despair.

One paradox of the political wars over the Neely killing is that the people who are outraged by his death are generally also up in arms about New York Mayor Eric Adams’s plan to put a lot of police on the subways—even though it’s quite likely that a faster police response would have saved Neely’s life. (Vasquez, the man who shot the video of Neely’s final moments, thought so.) But it’s also true that having police deal with people experiencing mental health crises poses its own problems, especially if the cops are not specifically trained for such situations. People with severe mental illness are at markedly higher risk of being killed during police interventions. (While a black man is about 2.5 times more likely to be killed by law enforcement than a white man, an untreated psychiatric condition on either man’s part would elevate that risk for him by as much as 16 times.) Special crisis-intervention teams may help. But the elephant in the room is the need for involuntary hospitalization and treatment, also strenuously opposed by the left. One of the very few progressive commentators to recognize this in discussions of Neely’s death is Washington Post columnist Eugene Robinson, who wrote:

We have neither the legal framework nor the inpatient facilities to compel an adult such as Neely to receive the kind of effective, long-term treatment that might have changed his life. We live with the consequences.

Adams, a black Democrat somewhat in the mold of the late Ed Koch, has strongly advocated involuntary hospitalization, angering progressives. In a speech after Penny was arraigned, Adams, who had been earlier criticized for not showing enough sympathy for Neely, said that “Jordan Neely’s life mattered” but also stressed the need for “a new consensus around what can and must be done for those living with serious mental illness and to take meaningful action despite resistance and pushback.” As he put it, “The tragic reality of severe mental illness is that some who suffer from it are at times unaware of their own need for care.” I have had some firsthand experience of this tragic truth, having watched a longtime close friend’s condition deteriorate due to a combination of bipolar disorder and substance abuse while I and several other friends unsuccessfully tried to steer him into treatment.

Neely’s terrible story certainly illustrates this reality. Despite assertions that the system failed him, he was repeatedly offered voluntary opportunities for treatment, which he spurned. (One of the system’s failures is that he was not detained, despite the warrant for his arrest, after leaving the treatment facility in February.) An effective mental health policy would be neither “conservative” nor “liberal”; it would certainly require large investments in social services. But the mere availability of facilities and treatment programs won’t suffice to ensure that people with severe mental illness will get the help they need. The New Yorker piece on Neely and systemic failures in dealing with mental illness examines the case of a homeless woman diagnosed with paranoid schizophrenia who is brought to a support center and offered help. Her story ends brutally: “One day in early December, she was admitted to an assisted-living facility; that night, she disappeared.”

IF A CRIMINAL CASE IS PURSUED against Daniel Penny, it will unfold regardless of these political conflicts; but it will continue to be a political football, especially in an election year when it has already become a polarizing national story. The right is already raising enormous sums of money for Penny’s defense; the left will no doubt continue protests.

Penny does not deserve to be demonized, much less painted as a racist with no evidence. But the label of “Good Samaritan” that some conservatives have applied to him rankles—even if a jury someday decides that Penny’s use of force was justified, or if a grand jury declines to indict him. One thing that struck me about the video is the lack of concern Penny seems to display toward the unconscious man on the floor as he rises to his feet and retrieves and puts on his cap. He does, after that, briefly approach Neely and move his arms as other passengers try to assist him; but his overall demeanor does not suggest someone seriously troubled by the fact that he may have at the very least caused serious injury. Of course, we don’t know what happened after the brief video ends, and it’s useful to remember that at the time Penny was probably still experiencing an adrenaline rush from the fight. But I would urge Penny’s supporters to hold off on the “Good Samaritan” analogies.

The recording also shows that Penny did not weaken his potentially dangerous hold on Neely despite the fact that two other people were helping restrain him—and waited for about 30 seconds to release Neely after a bystander, noticing that Neely appeared to have lost control of his bowels, warned that he could be dying. Penny did not appear to immediately respond, although the other man restraining Neely at that point did react to the warning. The ex-Marine’s defenders point out that after releasing Neely, he helped (on another bystander’s advice) to roll him on his side to make sure he didn’t choke on his saliva. While this suggests that Penny did not desire to end Neely’s life, it does not rule out the possibility that Penny recklessly used excessive force.

Writing in National Review, Andrew McCarthy, a former prosecutor, acknowledges that there are legally valid reasons to charge Penny, even though his use of force was “lawful at the start”:

At a certain point, though, Neely was subdued. While a civilian is still allowed to use force necessary to detain a threatening person until the police arrive, the force has to be proportionate to the threat. Neely is said by the coroner to have suffocated. So even though Penny and other passengers tried to roll him into a position that would enable breathing, this was arguably done too late, such that the intensity and duration of the headlock Penny employed could be deemed unreasonable. When a person dies from an arguably unreasonable use of defensive force, even though that person instigated the confrontation, a manslaughter charge is rightfully on the table.

Nonetheless, McCarthy believes that charges should not have been brought against Penny. A Manhattan jury, McCarthy writes, would be intimately familiar with the depredations inflicted by unruly and violent mentally ill homeless people on the subway and so will would be extremely unlikely to convict. And in the big picture, McCarthy suggests, justice is on Penny’s side, and the charges against Penny represent “social justice, not real justice.” Yet since McCarthy concedes that a “technical law violation” probably occurred, one could counter that he is arguing for a conservative version of “social justice” in which the righteous outrage of beleaguered subway riders should take precedence over just the law.

Given the passions around this case—and the fact that a man is dead—a trial may be the best way to air the facts. But it is also essential for reasonable voices across the political spectrum to speak up, to promote honest reporting, and to acknowledge the complexities of the case and the danger often posed by unstable and aggressive people while also affirming the value of all human life.