The Cost of Pardoning the Jan. 6th Defendants

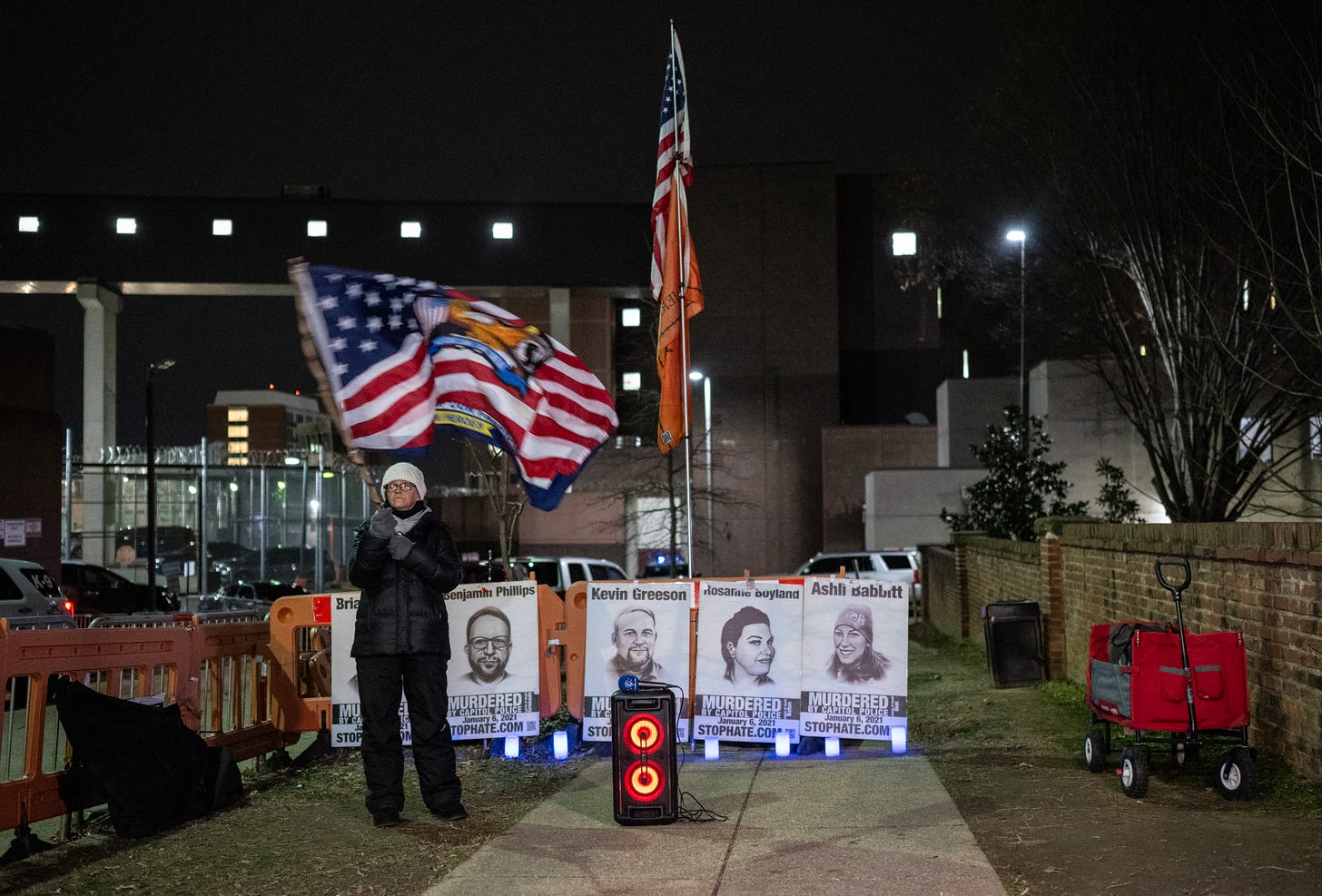

Trump suggests he will wipe away hundreds of convictions and end pending prosecutions.

IN HIS “PERSON OF THE YEAR” INTERVIEW with Time magazine, Donald J. Trump reiterated his campaign promise to pardon the Capitol rioters, claiming that “a vast majority of them should not be in jail.” While federal authorities continue to make new arrests, there have been upwards of 1,488 individuals charged across all fifty states and the District of Columbia for offenses ranging from misdemeanors to assault and seditious conspiracy. As of August 6, 2024, the Justice Department reported that there had been 894 individuals who pleaded guilty to a variety of charges. Another 223 have been convicted in trials. Some 562 have been sentenced to prison.

Among the defendants are individuals caught on tape brandishing stun guns, flagpoles, fire extinguishers, bike racks, batons, a metal whip, office furniture, bear spray, a tomahawk ax, a hockey stick, knuckle gloves, a baseball bat, a pitchfork, pieces of lumber, crutches, and even an explosive device during the attack in which approximately 140 police officers were assaulted.

If Trump pardons these individuals, what will it mean pragmatically for them? What will it mean for the American taxpayer? And what will it mean for justice?

Bear in mind that Trump would be squarely within his constitutional authority if he pardons every last one of them. Article II of the U.S. Constitution contains the pardon power, with its only textual constraint being a ban on pardons for impeachments. By tradition, the rationales for presidential pardons fall into three clusters: as a measure of mercy for someone convicted on shaky evidence or sentenced to overly harsh terms of incarceration or execution, as a political salve or “amnesty” to quell nationwide division and unrest, or out of self-interest and corruption. All of these are constitutional.

In Trump v. United States, the Supreme Court last summer deemed the pardon a “core” power, adding that the reasons for its exercise are beyond reproach or even scrutiny. Still, although the law does not sort “good” pardons from “bad” ones, logic, morality, and public policy do. A pardon to cover up and immunize a president’s own possible wrongdoing—which is arguably what happened when George H.W. Bush pardoned people convicted over the Iran–Contra scandal and when Trump pardoned cronies like Roger Stone and Paul Manafort—should be roundly scorned. Pay-to-play pardons—the specter of which got Bill Clinton in hot water when he pardoned the “fugitive financier” and mega tax evader Marc Rich, whose wife donated $450,000 to the Clinton presidential library—should likewise be condemned as utterly unacceptable. (Although Congress and the U.S. Attorney’s Office for the Southern District of New York investigated the propriety of the Rich pardon, the notion of oversight for presidential pardons is now utterly gone from public discourse and the law.1)

Pardons of violent offenders whose profiles suggest they might go on to commit violent crimes deserve special opprobrium. For example, Trump, in his final hours in office in 2021, commuted the life sentence of Jaime A. Davidson, who had been convicted of murder in 1993 for his role in the death of an undercover police officer in upstate New York. In 2024, Davidson was convicted of assaulting his wife and sentenced to three months in prison. Many of the January 6th insurrectionists fall into this category, which is a prime reason why Trump should not pardon them: Releasing them will make the public less safe.

IF TRUMP PARDONS THESE INDIVIDUALS, the public will also wind up paying the price in other, less obvious, ways.

Consider the case of Joe Biggs, a leader of the Proud Boys, who in August 2023 was sentenced in federal court in Florida to seventeen years for his convictions by a jury on seditious conspiracy; conspiracy to obstruct an official proceeding; obstruction of an official proceeding; conspiracy to use force, intimidation or threats to prevent officers of the U.S. from discharging their duties; interference with law enforcement during civil disorder; and destruction of government property. U.S. District Judge Timothy Kelly enhanced Biggs’s sentence for “terrorism” because he tore down a fence between police and rioters, which the judge deemed a “deliberate, meaningful step” in the chaos that day.

Biggs’s lawyer, Norm Pattis, has made clear that his client will seek a Trump pardon. January 6th was merely a “riot gone bad,” Pattis claims, and although “it was awkward, it was inconvenient, and it was sometimes violent,” there was “no attempt to overthrow the government” so it “shouldn’t cost anybody decades behind bars.” Biggs had sustained a head injury in Iraq and later became a correspondent for Infowars. Pattis argued that his military service should qualify him for a pardon because he “put his life on the line for the American people” and his conviction has cost him his “disability pension.” Said Pattis: “Regardless of what you say about January 6th, an afternoon shouldn’t cost he and his family a pension.”

A pardon, unlike a judicial exoneration, does not wipe out all evidence of a criminal conviction. If a person is incarcerated, a full pardon—like a lesser commutation—means they get out of jail. But it can also restore several rights and privileges that a felony conviction could otherwise take away, possibly for life, including:

bans on doing business with the federal government, including acting as a contractor;

restrictions on voting rights and jury rights;

bans on obtaining, receiving, transporting, or possessing any firearm or ammunition;

a ban on enlisting in the federal armed forces;

bans on obtaining certain federal licenses (such as U.S. Customs and import-export brokers);

bans on holding certain federal and state positions;

potential restrictions on other job prospects, such as labor organization posts, and banking or insurance company positions;

an increased sentencing range if convicted of future crimes;

restrictions on travel;

loss of parental rights; and

loss of certain public benefits and housing.

So for those convicted of January 6th crimes—whom Trump has called “hostages” and “patriots” for having been prosecuted over what was “a day of love”—a pardon could transform their lives, restoring freedom and a host of benefits.

Meanwhile, taxpayers will in some cases go from paying for these individuals’ prison time to paying for their pensions. And one shudders to think what some of these Trump loyalists—dangerous on January 6th and now perhaps emboldened and more radicalized—might get up to when they’re no longer behind bars.

Although the Supreme Court majority in Trump v. U.S. disputed Justice Amy Coney Barrett’s suggestion in her concurring opinion that the ruling could “hamstring” an attempt to prosecute a former president for bribery, practically speaking she was probably correct.