It’s Thursday Night Bulwark! I’m not on the livestream tonight, but come hang out at 8:00 p.m. Eastern with Tim Miller, Amanda Carpenter, Bill Kristol, and Ben Parker.

I hope you twist the knife on Tim for the LSU coaching hire in the chat.

As always: It’s only for members of Bulwark+.

Also: I’m going off-topic today. If it’s not your jam, my feelings won’t be hurt.

1. There Shall Come a Blockchain

I’m a longtime crypto-skeptic, but even though I find the idea of non-state currency to be slightly ridiculous, I’m interested in the idea of the decentralized internet.

My problem was that no matter how much I read about the Web3 world, I couldn’t quite get my head around it. So after dabbling with some crypto exchanges for a few months, this week I took the plunge and bought a couple of NFTs.1 And I thought it might be worthwhile to share my impressions of the technology after getting my hands dirty.

(1) The blockchain is not ready for prime time.

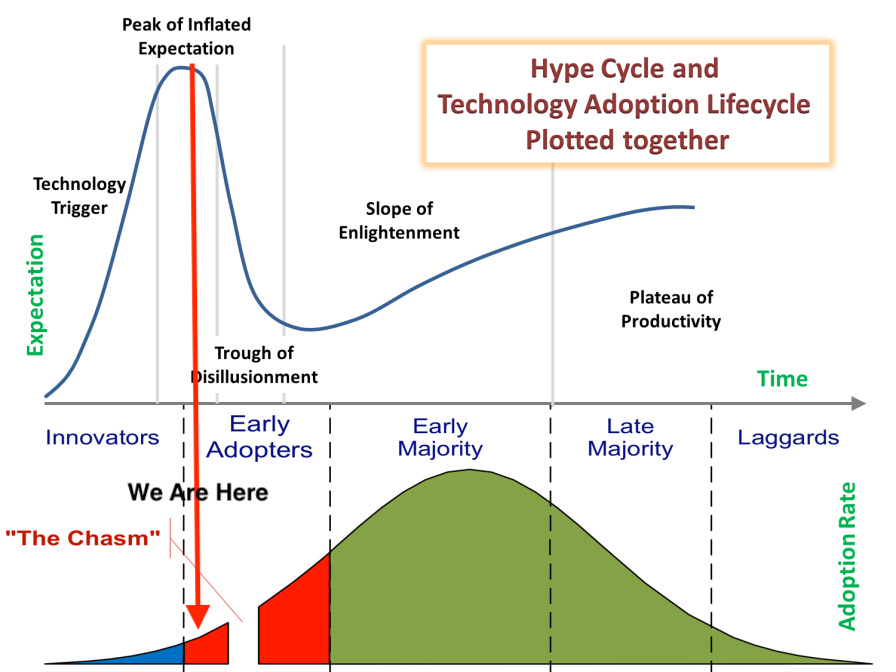

There’s a classic diagram that plots the theoretical potential of new technology against the technology’s adoption curve. This is it:

I suspect that blockchain is currently where the red arrow is pointing: About a quarter of the way through the early adopter cycle and probably just before “the chasm.”

What is the chasm? It’s the moment when the new technology stalls out among the first cohort of early adopters and any speculative bubbles based on hype pop. Many technological innovations die here. But the ones that cross it often go on to become widely adopted and ingrained in our lives.

The reason I say that blockchain-based applications are post-innovator but pre-chasm is that I’m a pretty typical early adopter for just about everything. (I only recently parted with my Toshiba HD-DVD player.) I have made my living on the internet since 2001. I am about as tech literate as someone who is not an actual engineer can be.

And me trying to buy crypto, set up a wallet, get onto an exchange, and purchase an NFT was like watching your grandmother trying to program a VCR.2 If it takes me a long while to figure out my way around the blockchain, then we are many, many steps removed from a place where the technology is usable even for the top-quartile of the general public.

Until there are automated intermediate steps where people can point and click purchases using a credit card and wallet security has been solved to the point where the average Karen and Chad aren’t doomed if they lose their recovery passwords, this technology is going to remain on the bleeding edge.

An internet analogy: blockchain is about where home internet was in the Prodigy/CompuServe/pre-AOL days.

(2) There’s a LOT of speculation.

The NFT project I bought into is going to mint a total of 10,000 tokens. As of this writing, about a quarter of them have been purchased. And about 5 percent of them are already being offered for sale on secondary markets.

This suggests that the people who bought these NFTs did so not out of interest in the project, but as a lottery ticket. If this project turned into the next Bored Ape Yacht Club, then they could get rich. And when these NFTs didn’t pop right away, they went looking to unload them so they could move on to the next thing.

(3) Ethereum and Bitcoin are commodities, not currencies.

Cryptocurrencies aren’t really “currency.” They’re commodities, which is to say, stores of value—closer to gold or pork bellies, than to coins or paper money. You can trade these crypto commodities for other digital commodities. But crypto is so volatile that there’s no real reason to do that. It is not uncommon to see ETH and BTC move up or down 5 percent in value relative to the USD over a 24-hour period. A commodity that volatile isn’t useful qua currency.

If crypto hits the mass adoption part of the curve, it’s going to be people who buy ETH with USD right at the moment of purchasing whatever end-good they’re after. At which point crypto really just becomes a layer of math between the currency and the good being purchased.

(4) Ethereum and Bitcoin both have supply constraints.

In crypto world there are Ethereum and Bitcoin maximalists—people who believe that one of those currencies is dramatically undervalued and destined to rule supreme.

The theory behind the Bitcoin maxis is that since Bitcoin will eventually have an immutable, finite number of coins minted, it will someday become the standard store of value on the blockchain because it will be both the oldest and most stable cryptocurrency.

The Ethereum maxis argue that Ethereum is the only crypto which you can actually use to purchase tokens, so it has a big utility advantage over bitcoin.

And while the supply of Ethereum is, in theory, infinite, in practice that supply is going to be governed by the law of diminishing returns.

The more Ethereum is mined, the more work it takes to mine the next block.

What this means is that there is a practical limit to total circulation, even though Ethereum does not have a hard limit, as Bitcoin does.

(5) DAOs are a mashup of a co-op with a hedge fund.

The DAO—a decentralized, autonomous organization—is the new hotness in blockchain world. You can read the wikipedia page here if you want. But it all boils down to what we used to call co-ops, or communes, back in the analogue world.

A group of people pool resources and have fractional ownership of the enterprise. Everyone contributes as much time and direction as he wants. Organizational decisions are made by vote.

The NFT I bought is part of a DAO. Here’s how it works:

I paid some money for the NFT. In return I got a funny looking image that I “own.”

Of that money, 70 percent goes to the engineering team building the NFTs.

The other 30 percent goes into a big pot owned by the DAO. (Meaning: Owned by me and everyone else who bought the NFTs.)

The purpose of this pot of money is to buy and sell other NFTs, which will then belong to the group. The blockchain gives each token holder watch-only permissions so that they have fractional ownership of whatever the DAO decides to buy.3

This is an interesting way to create and run a hedge fund!

(6) The blockchain is the Wild West right now. But it probably won’t be for forever.

There is a gold-rush mentality out in blockchain world where everyone is trying to be early and get rich and some of them can because as of yet, there ain’t no law in Deadwood.

It feels a lot like the early days of the internet in the mid-’90s.

There is also a lot of idealism in blockchain world where people say things like The decentralized web will free us from corporate/state/whatever oppression!

And people said those things about the internet in 1995, too.

Yet today, the internet as we know it is largely controlled by Amazon, Google, Facebook, and Apple. These big corporations figured out how to annex the Wild West and make it a vassal state. And authoritarian governments—far from being threatened by the internet—have figured out how to use it to control their populations more completely than in the pre-internet days, even.

Maybe blockchain is different. But I wouldn’t bet on it. At some point Big Business and state actors will probably figure out how to dominate it. And I’m not sure the results will be a net good for normal people.

2. Contra Nature

But the big thing I’ve learned is that this entire blockchain, NFT, crypto movement is a rebellion against the fundamental nature of the internet.

What is the internet, at its essence?

A machine that reduces all marginal costs to zero.

That’s the central fact of the internet. And it created an entirely new mode of existence for everything it touched because it killed scarcity. Everything on the internet exists in a post-scarcity state.

Now here’s the Big Idea:

The blockchain and NFTs are an elaborate mechanisms to create scarcity where there is none.

I said that the NFT I bought meant that I “owned” the picture. Well, here’s the picture I own:

Would you like to have it? Go ahead. This is the internet. Take a screenshot. Import it to your photo library. You own it now, too. Text it to your mom and she owns it. Post it on Twitter and anyone who sees it can own it.

But thanks to the blockchain, we have an irreducibly complex math problem which creates a single version of this picture that only I can actually “own.” The blockchain proves that I’m the “real” owner and you merely own “copies” of my picture.

In a way, this is just as radical a shift as the internet destroying marginal costs.

Is this shift ultimately a good thing? I don’t know. Only humans would spend 5,000 years figuring out how to defeat information scarcity and then spend the next 20 years trying to re-create it artificially.4

But there is something deeply human about the desire for scarcity.

Living in a world with no marginal costs can be unsettling. It’s the kind of idea that gets Mark Zuckerberg all tingly because he’s a messianic robot. But for the rest of us, this state is sometimes helpful, but also sometimes destabilizing and sometimes alienating. Was human society really meant to have every village crackpot in possession of a megaphone enabling them to scream at every other person on the planet? Haven’t we spent hundreds of years organizing ourselves around the idea of gatekeeping functions?

But the world of scarcity, on the other hand, is baked into our DNA.

Here’s a funny story about my NFT:

The NFTs in my project are designed so that even though there are only 10,000 of them, some of the images are more “rare” than others. This rarity doesn’t matter. At all. The owner of the most rare token gets the same fractional voting share in the DAO as the owner of the most common token.

And yet, after I got my little guy up there, I became obsessed with the idea that it didn’t score high enough on the rarity index.

Is this stupid? Oh yes. Deeply stupid. But it’s also very human. It’s the same collector’s impulse that leads us to purchase baseball cards, or first-edition books, or art. It’s the kind of impulse that the logic of the internet abhors—but which has always been part of meatspace. And probably always will be.

By the by, if this sort of discussion is your jam, you can get more of it. Every day.

3. Complex Chaos

A good essay about chaos and complex systems:

One of the oldest jokes in physics is that you should begin by imagining a spherical cow. No, physicists don’t think that cows are spherical; we know this is a ridiculous approximation. However, there are cases where it’s a useful approximation, as it’s much easier to predict the behavior of a spherical mass than a cow-shaped one. In fact, so long as certain properties don’t really matter for the sake of the problem you’re trying to solve, this simplistic view of the universe can help us arrive at accurate-enough answers quickly and easily. But when you go beyond single, individual particles (or cows) to chaotic, interacting, complex systems, the story changes significantly.

For hundreds of years, going all the way back to even before the time of Newton, the way we approached problems was always to model a simple version of it that we could solve, and then to model additional complexity atop it. Unfortunately, this type of oversimplification causes us to miss out on the contributions of multiple important effects:

chaotic ones that arise from many-body interactions extending all the way to the system’s boundaries,

feedback effects that arise from the evolution of the system further affecting the system itself,

and inherently quantum ones that can propagate throughout the system, rather than remaining confined to a single location.

On October 5, 2021, the Nobel Prize in physics was awarded to Syukuro Manabe, Klaus Hasselmann, and Giorgio Parisi for their work on complex systems. While it might seem like the first half of the prize, going to two climate scientists, and the second half, going to a condensed matter theorist, are completely unrelated, the umbrella of “complex systems” is more than big enough to hold them all. Here’s the science of why.

I’m not going to broadcast which NFT project I bought into because I’m not writing this to be a tout. If you want details, you can email me and I’ll tell you. But the point of this essay isn’t to pump interest in a particular project.

A VCR was a machine that recorded television shows via magnetic tape. It could be programmed to record a given station at a given time using an IR remote control with approximately 70 buttons, each of which was 1 mm by 2.5 mm. Old people viewed these devices as equivalent to sorcery

There’s a lot of technical gobbledygook here, but what “watch only” means is that all members of the DAO can “own” a fractional share of the holdings, individuals can’t sell their fractional shares. Only the group can decide a particular holding.

If I was going to be glib, I’d say that crypto is like the organic counter-revolution to the GMO revolution which defeated famine. We have a way to feed everyone! Yay! Now let’s rebel against this new technology and make food production harder again!