Thanks for reading The Bulwark. Read more of our stuff, every day, for free. Or sign up for the full boat at Bulwark+.

1. Approval

Dan Pfeiffer has an interesting little exegesis on Joe Biden’s approval numbers over here. Mostly it’s about polarization and the persistent gap in R and D attitudes. Today that gap is so large that getting to 53.8 percent approval (where Biden is now) is hard.

Two nuggets from Pfeiffer for you:

(1) “As an example of how much things have changed, Bill Clinton’s approval rating among Republicans was 41 percent in a Gallup poll immediately after being impeached by a Republican Congress.”

Holy crap! I’d forgotten that. A truly amazing feat.

(2) This bit on Biden and negative partisanship is very smart:

[W]e live in an era of negative partisanship—where hatred for the other party is the biggest driving factor in political action. This is why Biden’s policies can poll in the seventies, and his approval rating can be in the low fifties. . . .

Therefore, as we think about 2022, we should focus a little more on Biden’s disapproval rating. In the aforementioned ABC/Washington Post poll, only 42 percent of respondents disapprove of Biden’s job performance. Based on recent history, this number is impressively low. At this point in his Presidency, Trump’s disapproval was 53 percent. Biden’s number is only three points higher than Bill Clinton’s at the 100-day mark in a radically less polarized era.

Biden hasn’t gotten Republican voters to like him, but he has prevented them from hating him — a truly remarkable achievement.

Yes. Keep an eye on Biden’s disapproval numbers as much as his approval numbers.

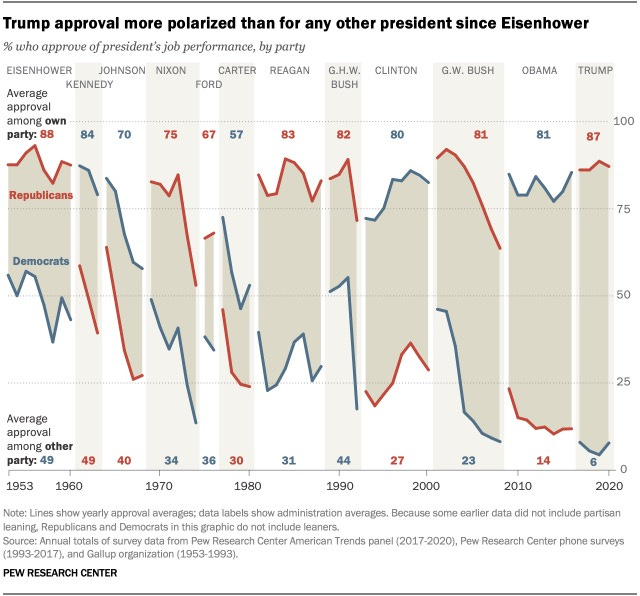

I want you to look at approval rating splits by party for the last 70 years:

Yes, the difference by party affiliation has been growing since Reagan, but that’s not what concerns me most.

What scares the crap out of me is that beginning in the Obama years, the direction of partisan approval ratings started diverging.

From Ike to W, partisans were always more favorable to presidents from their own party. But even though there was a gulf between them, both Democrats and Republicans moved in the same directions—like they were tethered together.

So when Ike’s popularity increased among Republicans, it increased among Democrats, too. Just at a lower valence.

And when George H.W. Bush’s popularity decreased among Democrats, it decreased among Republicans, too.

But starting around 2011, something weird started happening:

Obama’s approval rating among Democrats went up—at the same time that it went down among Republicans.

That disassociation only lasted for a year or two. But then it happened again with Trump. For the first two years, Republican approval for Trump increased at the same time it was decreasing among Democrats. And then for the second two years that dynamic flipped.

The only time we’d seen this kind of directional divergence before was during the Ford presidency, but the circumstances there were weird enough that I consider it an aberration.

But it’s been close to the norm for the last decade.

Here is why this directional divergence worries me:

If Rs and Ds have a persistent partisan split in how they react to presidents, that’s not great. But we can live with it, so long as they both inhabit the same reality.

And we measure this shared reality by watching how the groups move in their approval. So long as they go up, or down, together, it means that they’re looking at and living in the same world.

Once they start moving in opposite directions it’s a sign that the two groups are living in totally different worlds.

Think I’m exaggerating?

90 percent of Democrats and 75 percent of Independents think the Derek Chauvin verdict was correct. But 46 percent of Republicans think Chauvin was wrongfully convicted.

Then there’s this:

Completely, totally, different realities.

When you see the red and blue lines moving in opposite directions in that first graph, it tells you that people no longer agree on either (a) what the world looks like or (b) what the world should look like.

What happens when we stop agreeing about basic reality? Nothing good.

Look: The time to try to fix a catastrophe is before it fully manifests. That’s what we’re doing at The Bulwark. Come with us.

2. This Is Also Bad

Per Rolling Stone, lots of drugs happening at Fort Bragg:

In recent years, whistleblowers have alleged that the use of hard drugs is widespread among special operators. Three unnamed Navy SEALs told CBS in 2017 that various teammates of theirs had tested positive for cocaine, methamphetamine, MDMA, and heroin, and that the substance-abuse problem was “growing.” In 2014, a Navy SEAL named Angel Martinez-Ramos pleaded guilty after being arrested at Miami’s airport with 10 kilos of cocaine in his carry-on. In 2015, former SEAL James Matthews got pulled over in New Jersey towing a trailer loaded with $1.4 million worth of marijuana. In 2018, former senior special-forces sergeants Daniel Gould and Henry Royer were busted trying to import punching bags that had been gutted and packed with cocaine from Colombia. These are highlights of a significantly lengthier list.

In response to these and other embarrassments, including President Trump’s pardon of former SEAL Eddie “Freaking Evil” Gallagher, the commander of all special-operations forces, Gen. Richard Clarke, ordered a “comprehensive ethics review” in August 2019. The report, released in early 2020, was mostly a whitewash, full of vague language about improving leadership and accountability. It did cite, however, what it described as “an unhealthy sense of entitlement” among special operators.

It’s an amazing piece. And the drugs mixed with the unhealthy sense of entitlement has resulted in a lot of dead soldiers:

Dumas had been arrested numerous times in North Carolina on charges ranging from making terroristic threats to impersonating a cop, yet had never been prosecuted. Lavigne, too, managed to escape prosecution on multiple occasions, though he had been suspected of felonies that included harboring an escapee, maintaining a vehicle or dwelling to manufacture a controlled substance, and even murder.

In 2018, Lavigne shot and killed his best friend, a Green Beret named Mark Leshikar, in an inexplicable, drug-fueled altercation that no one witnessed but two little girls. Sheriff’s deputies took him to the station, but he was never placed under arrest or charged with a crime. He was taken home that same night by some of his Delta Force teammates. “They are a very hush-hush community,” says Diane Ballard, a police detective in the tiny town of Vass, where numerous Delta Force operators, current and retired, own houses. “They do what they want.”

Most immediately, though, the discovery of Lavigne’s body represented a problem for the leadership at Fort Bragg. Army authorities won’t disclose the total number of soldiers stationed there who died in 2020, but Lavigne was one of a spate of homicides and suicides that brought the tally up to at least 44, pushing Fort Bragg to a decisive first-place finish in a race no one wanted to win. It far surpassed Fort Hood, where 28 soldier deaths in 2020 led to a congressional investigation, a sweeping indictment of the installation’s “toxic culture,” and the dismissal of most of the chain of command. To date, the House Armed Services Committee seems not to have noticed the similar pattern at Fort Bragg.

At least part of the problem is that law enforcement seems to be basically nil. There is no Jack Reacher:

The deaths began in January 2020, when a 19-year-old Texan’s body was discovered in his bunk in an advanced state of decomposition; the Army has not disclosed the cause, and one year later, the investigation remains ongoing. The same is true in the case of a young Ohioan, a Green Beret candidate, who in March was found “unresponsive” in his barracks. In late May, a 21-year-old enlisted man from California was killed — beheaded, in fact — while on a camping trip with six of his fellow paratroopers; once again, no arrests have been made in the case. In November, yet another soldier, a 24-year-old Texan, was discovered “unresponsive” in his bunk, with no further details from the Army. By the end of the year, there had been 21 suicides at Fort Bragg, more than at any other U.S. military post.

To cap off a freakish year at Fort Bragg, just three weeks after Lavigne and Dumas turned up dead, a 31-year-old combat medic assigned to Special Forces named Keith Lewis shot and killed his pregnant wife, Sarah Lewis, an Air Force veteran who was due to give birth at any moment. Keith’s mom, Lynda Lewis, tells me that her son should have been expelled from the Army back in 2016, when he assaulted Sarah and got into an armed standoff with the Fayetteville police. “He called me and said, ‘Mom, I’ve got a gun to my head. I hurt Sarah, and my career is ruined.’ I talked to him for a long time. He finally put the gun down.” In the aftermath, Lynda says, “There were no real repercussions.”

Would be helpful if the Biden administration could spare some attention for this problem, too.

3. The Black Card

It’s real, and it’s spectacular:

The Centurion Card, better known as “the black card,” began as a myth before American Express decided to make it a reality. “There had been rumors going around that we had this ultra-exclusive black card for elite customers,” Amex executive Doug Smith told the fact-checking website Snopes. “It wasn’t true, but we decided to capitalize on the idea anyway.”

The no-limit black card, issued by invitation only, instantly identifies its holder as what’s known in the trade as a “whale”—someone with vast resources. Amex won’t say what it takes to get an invite, but word on the street is that you must have been a Platinum cardholder for at least a year, ringing up a minimum of $350,000 in annual charges. . . .

According to Snopes, one Centurion cardholder requested a handful of authentic Dead Sea Sand for a child’s school project. Amex dispatched an agent via motorcycle to obtain the sand and courier it to London. Another black card holder had Amex plan their entire wedding. A third wanted to purchase the actual horse Kevin Costner rode in the film Dances with Wolves—the animal was tracked down in Mexico and delivered to the client in Europe. The sky’s the limit.

In November 2015, when Chinese billionaire Liu Yiquian bought a Modigliani reclining nude at auction for $170 million, he said he intended to put it on his black card. The year before, he’d reportedly used the card to purchase a $36 million Ming dynasty teacup. (Amex won’t comment on private transactions.) The travel points from the Modigliani purchase alone would ensure Yiquian’s family free first-class travel and accommodations for life—not that they needed them.