The Devastating Portrait of Postpartum Depression in ‘Fleishman Is in Trouble’

Struggling new mothers need to know they're not alone.

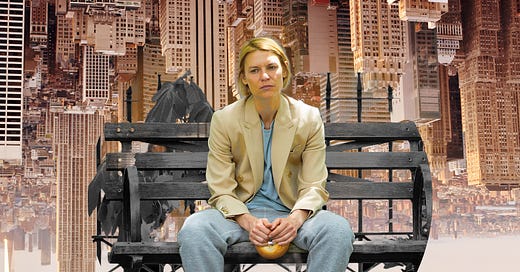

I was worried Fleishman Is in Trouble would not translate to television, that the FX/Hulu production would not match the 2019 novel’s humor, insight and compassion. But Taffy Brodesser-Akner has done a masterful job adapting her own book, and the TV series actually increased the story’s power for me. What struck me—after the brilliance of the acting, writing and direction—was how acutely I felt the depiction of Rachel Fleishman’s postpartum breakdown.

Because its portrayal was eerily similar to mine.

Rachel (Claire Danes) was raised by her remote, austere grandmother in Baltimore after her mother died when Rachel was almost too young to remember her. Although her mother had been Jewish, her grandmother sent Rachel to an all-girl, Catholic prep school where she felt excluded and friendless. Not just because of her religion, but because she was surrounded by girls who were born to wealth and privilege. Rachel bootstraps herself out of her humble circumstances, but the price she pays is that she depends only on herself and is very much alone. When she meets Toby Fleishman (Jesse Eisenberg) and then his effusive, tight-knit, observant Jewish family, she thinks she’s finally found the antidote to the gaping hole in her heart.

But pregnancy has other plans for her. Rachel is used to being in charge. She is independent and is unapologetically dominant in her job. Despite her intense desire for a family of her own, the lack of control inherent in lending your body to a creature growing inside you unsettles her. So is her new status as a sort of symbol rather than a person in her own right. She is passed over for a promotion, she’s tired all the time, and she can’t wear the stylish work clothes she’s used to. Even her beloved Toby treats her differently. Her formerly accepting, non-patriarchal husband acts as if she were a personal science experiment, telling her what she can and can’t eat for the health of their baby.

These first intimations of disorder in Rachel’s controlled adult life mutate into utter chaos after her daughter’s needlessly traumatic birth. While Toby is out of the delivery room for a moment dealing with coworkers, an unfamiliar and unconscionable OB-GYN breaks Rachel’s amniotic sac without her consent. In agony and feeling completely violated, she is forced to give birth sedated—strapped to and splayed on a gurney—by C-section. Suffering from PTSD and in so much psychic and physical pain, she has nothing left to give her new baby. Every day, she wears the same sweatpants, sweatshirt, and Uggs she wore when she left the hospital. She has no one to talk to during the day. Toby is doing rounds at his hospital. Her colleagues at work seem like they’re in a past life. The moms in her prenatal yoga group treat her depression as if it were contagious. She waits for the baby to sleep to have the freedom to weep uncontrollably on the floor of her bedroom, what she mordantly calls her “Me Time,” which is also the name of the episode.

Their pediatrician tells Rachel and Toby that their daughter might not be smiling yet because “Smiling is an imitative behavior,” implying Rachel’s turmoil is to blame. Toby suggests psychotherapy and Rachel responds, “I don’t need therapy! I need help with this baby!” So, they hire a nanny, Mona, and as soon as Mona takes their crying daughter out of Rachel's arms and into hers, the baby starts cooing peacefully. “I have a calm energy,” Mona says.

After I watched both “Free Pass” and “Me Time”—the first of which tells the story from Toby’s perspective, the second Rachel’s—I was chilled. I felt my own experience with postpartum anxiety and depression mirrored back at me.

Like Rachel, I had a parent who died before I reached adulthood and my other parent was frequently remote and emotionally unavailable. I am Jewish but went to an all-girls prep school on the Upper East Side of Manhattan that was decidedly not. The Preppy Handbook was my Torah. I used my creativity and adaptation skills to blend in as best I could, but on a socio-economic level, I couldn’t compete. In Fleishman Is in Trouble, a friend describing Rachel says, “the lack of money and proximity created an outsider’s desperation in her. But also, sophistication is a language; you’re either born speaking it, or you’ll always speak it with an accent.” I had to pause and rewind twice.

Like Rachel, I experienced traumatic things at the beginning of my pregnancy. Though, unlike Rachel, I had a wonderful OB-GYN who was actually there for my delivery. She advised me because of my history I was likely to have some kind of postpartum reaction, but I felt so healthy, strong and happy during my second trimester that I willfully ignored her warning. I do remember saying to her as the due date approached, “It almost never happens you 100 percent know in advance that your life is going to change completely in a day, but having a baby is I guess the exception.”

And it was true, but not in the way I’d expected and hoped for. Like Rachel, I had a C-section, though mine was planned. My baby was upside-down and backwards. My doctors were skilled and sensitive, but I was still drugged up and arms akimbo on the operating table like Jesus on the cross. All I wanted to do was sleep. I felt a vague tugging and pressure, but giving birth was literally and figuratively an out-of-body experience for me. I heard my baby cry and my partner was crying also from happiness and I played along because I knew that’s what I should do. I felt no joy, I felt no excitement, I felt no curiosity, I just wanted to keep sleeping.

I was in so much pain. I wasn’t able to get my baby to latch properly for feedings and my son was losing weight. My partner was at work all day and even though I had a baby nurse, I always felt tired, lonely and scared. I couldn’t believe the hospital had let me leave when I was clearly incapable of taking care of this new life. I couldn’t figure out what was happening. I had wanted this baby. Desperately. I had always wanted one, but I wasn’t even sure I could get pregnant until I did accidentally.

So why wasn’t I happy? “You must be blissful,” well-meaning friends would say, and I’d nod and smile but inside I wanted to crumple up and disappear. I didn’t deserve this miracle. I could see he was cute, and he was an “easy” baby. He slept and ate well. His caregivers told me what a good boy he was. But other than going through the motions and doing my duty by him, I felt no real affection for the child I’d previously craved. I felt immensely guilty and ungrateful. I could hear my relatives’ thoughts: “But she has so much help! She can sleep whenever she wants. She can go take a walk, go have lunch with friends. What’s her problem?”

Worse than their judgments were my own. Anything they might criticize me for, I would multiply internally by five. Because every time I nursed my baby or held him, I looked into his eyes and thought the same thing Rachel Fleishman thought: “Rachel looked down and knew that the baby knew what she was thinking. She knew and would never forgive her.” I was single-handedly ruining my child with my total lack of maternal instinct. In my mind, this newborn was already smarter and more intuitive than I was in my late 30s. My grandmother, my mom, and now I had no idea how to be a Good Mother. And other than pining for my boyfriend to come home from work and relying heavily upon my baby nurse and then nanny, I told no one because of my deep shame. Who would be interested in the complaints of a selfish, unloving, and unlovable upper-middle class woman?

Thank goodness, another mom—who was just an acquaintance then but is a dear friend of mine now—recognized the signs of postpartum depression in my face and my disposition from her own experience, and told me where to go for help. With a lot of excellent therapy and the right medications, I got through the first difficult year somewhat intact. But Claire Danes’s portrayal of Rachel’s first breakdown was stunningly real and potent. Her past, her helplessness in the face of trauma, her inarticulate grief and pain she interprets as innate, generational brokenness, and Toby, who just wishes someone else would help “fix” Rachel and make her the woman she was before she had his baby, who is resentful of Rachel handing the kids off to the nanny so she can feel somewhat herself again, all rang painfully true for me.

Brodesser-Akner’s brilliance in portraying this experience from both sides, Toby’s and Rachel’s, is superlative. As much as Toby wants to be helpful, Rachel’s trauma is incomprehensible to anyone who hasn’t gone through it themselves, and it makes her feel like she is stranded on an unknown island with no rescue in sight. My greatest hope is that the show will help other mothers struggling from this awful syndrome understand that they are not alone and that there is help out there for them. Things do indeed get better. And much, much better, at that.

Fifteen years later, that baby I thought I had failed, the one I knew I’d ruined, is now a bright, funny, well-adjusted and well-loved teenager. He’s even happy, as far as teenagers can admit to being happy. Babies are much more flexible and resilient than we are led to believe in the “What to Expect'' books. Despite their parents’ plentiful missteps, anxieties, and fumbling, my children, like the Fleishman children, are good, thoughtful, solid individuals well on their way to becoming (I hope) even more fully realized adults than the ones who are raising them.