As our fractured republic contemplates the very real possibility that Election Day will not be the climactic ending of this long slog of a campaign season, but rather just the beginning of a new phase of contention, it is worth looking back at what happened in the aftermath of another contested election—that of 1876, when 19 electoral votes remained in dispute and both sides claimed the presidency.

The Republican party was founded in 1854—a coalition of Whigs, Free-Soilers, wayward Democrats, and others who joined together in opposition to extending slavery into Western territories. In 1863, during the Civil War, the first Republican president, Abraham Lincoln, issued the Emancipation Proclamation, freeing the slaves in the Confederacy. In early 1865, a Republican majority in Congress pushed through the Thirteenth Amendment abolishing slavery; it was ratified before the end of that year.

Lincoln’s successor, Andrew Johnson, a Democrat, was less supportive of equality for formerly enslaved Americans. Congressional Republicans reacted by passing the Civil Rights Act of 1866 (Johnson had vetoed the bill the year before), along with other laws aimed at facilitating Reconstruction. The statute—which wouldn’t be enacted until after the 1868 ratification of the Fourteenth Amendment—mandated civil rights protections for persons of African descent in the United States.

In the 1868 election, Ulysses S. Grant, the general who had commanded the U.S. Army during the war, succeeded Johnson as president. A Republican, Grant was committed to Reconstruction. In 1870, the Fifteenth Amendment was ratified, giving black men a constitutional right to vote.

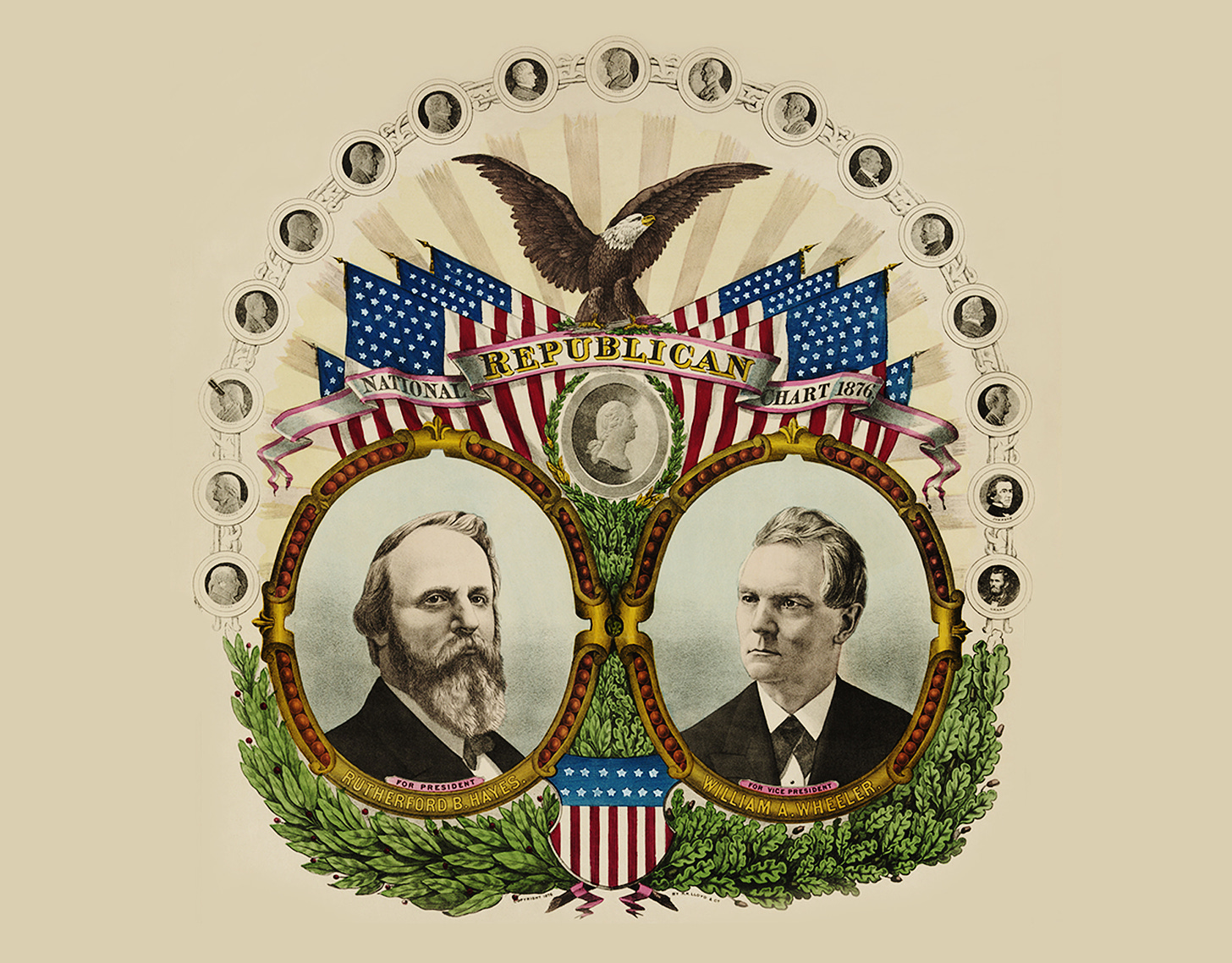

By 1873, America was in an economic depression (as it is now). In the 1874 midterm elections, Democrats took control of the House of Representatives while Republicans held the Senate (as happened in 2018). With Grant opting not to run for a third term in 1876, the presidential race that year was between two governors: Democrat Samuel Tilden of New York and Republican Rutherford B. Hayes of Ohio.

The election returns from Louisiana, Florida, and South Carolina left 19 dispositive electoral votes in dispute, and no clear winner. Both candidates submitted electors from these three states.

The split Congress came to a compromise, appointing a bipartisan commission of five House members, five Senate members and five Supreme Court justices to definitively award the contested electoral votes. The commission worked to investigate the returns in public, as “there was a great desire to witness a fair count,” according to the New York Times. The commission, in a series of party-line votes, handed Hayes the presidency by a single electoral vote. But a handful of congressional Democrats continued to object and filibuster. Their compliance was only obtained once national party leaders secretly brokered a deal—dubbed by historians the Compromise of 1877—whereby Republicans agreed to abandon Reconstruction efforts by removing federal troops from the South and allowing “home rule” in exchange for Democrats accepting Hayes in the White House. As a consequence of resolving the disputed presidential election, discrimination, disenfranchisement, and racial violence roared back to life in the South.

Fast forward to 2020.

The RNC convention last week confirmed that the Republican party has embraced a platform of bigotry over policy, with Nikki Haley disavowing black Americans’ experiences with racism as “a lie,” and with prominent placement given to the Missourians who brandished guns at a Black Lives Matter protest. In a recent CBS News poll of registered voters, Republican respondents said they considered the death toll from COVID-19 in the United States to be “acceptable” by a 57-43 margin, and averred that America is “better off” than it was four years ago (when tens of thousands of Americans hadn’t yet been killed by the coronavirus) by a margin of 75-25. Asked if Trump will accept the results of the election, White House Press Secretary Kayleigh McEnany said that he will “see what happens.”

When it comes to our polarized political and cultural climate, we have long moved beyond hyperbole. The frailty of American democracy today increasingly begs comparison with the chapter of U.S. history in which Americans killed nearly 750,000 fellow Americans—due largely to racism, economic devastation, and differing views on what “rights” actually mean.

One huge difference between then and now: The Republican party is no longer the party of inclusion, unity, and tolerance. And the occupant of the White House is a far cry from the likes of Abraham Lincoln and Ulysses S. Grant.