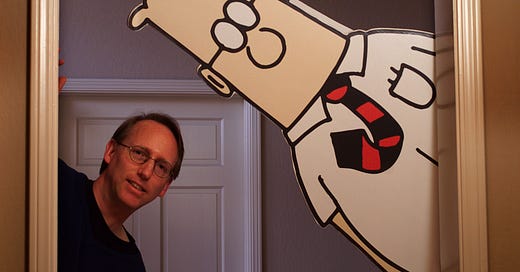

The Foolishness of Scott Adams

His argument for racial prejudice isn’t just pernicious. It’s stupid.

Scott Adams, the cartoonist behind the comic strip Dilbert, has been canceled for racism. In a video livestream last Wednesday, he declared:

“I resign from the hate group called black Americans.” (Adams is white.)

“The best advice I would give to white people is to get the hell away from black people. Just get the fuck away.”

“It makes no sense whatsoever as a white citizen of America to try to help black citizens anymore. . . . It’s over. Don’t even think it’s worth trying.”

Adams wasn’t done. The next day, he continued:

“I’ve designated that to be a hate group—black Americans—a hate group.”

“If you’re white, don’t live in a black neighborhood. It’s too dangerous.”

“White people trying to help black America for decades and decades has completely failed. And we should just stop doing it. [Because] all we got is called racists.”

Most Americans would consider these statements vile. But Adams swears he’s preaching practicality, not hate. “It wasn’t because I hated anybody,” he pleaded in his daily livestream on Monday. “I was concerned that somebody hated me.” That somebody, he argued, was black people. “The whole point was to get away from racists,” he insisted.

A week after his original rant, Adams still claims that nobody has disagreed with his main point: that to steer clear of people who dislike you, it’s sensible for white people to avoid black people, and vice versa.

Adams is wrong. Not just morally, but practically. His advice is empirically unfounded and would make everything worse. Here are a few reasons why.

1. The inference from race to hostility is completely unsound.

The trigger for Adams’s Feb. 22 rant was a recent Rasmussen Reports poll that asked a thousand American adults whether they agreed or disagreed with the statement, “It’s okay to be white.” Fifty-three percent of black respondents agreed, 26 percent disagreed, and 21 percent said they weren’t sure. In other words, black respondents were twice as likely to agree as to disagree.

But Adams contorted the numbers to make the poll look worse. He added the not-sure responses (21 percent) to the disagree responses (26 percent) and concluded—in highly misleading language—that “nearly half of that team doesn’t think I’m okay to be white.”

The poll had several problems. For starters, “It’s okay to be white” sounds innocuous, but it’s also a trolling slogan, and some nonwhite respondents may have recognized it as such. Alternatively, it may have struck some respondents as a dare or just plain weird. And the margin of error for the black subsample was pretty big: about 8 percent.

Eventually, Adams admitted that the poll was unreliable. But instead of rethinking his conclusion, he said the numbers didn’t matter. He insisted that his point would stand even if the real numbers were only half as big as the poll indicated.

“Suppose it’s a quarter of black Americans,” not 47 percent, who were “not willing to say being white’s okay. Would that change my point?” he asked. He concluded, “It wouldn’t be any different at all.”

That’s crazy. If the numbers are off by half, the percentage of black respondents who disagreed with “It’s okay to be white” would be 13. That’s statistically indistinguishable from the 12 percent of all respondents—white, black, whatever—who disagreed with the statement.

In fact, judging by Adams’s anecdotal evidence, 13 percent would be high. He says he’s had “zero bad experiences” with black people. “My personal interactions with black Americans—and even Africans, actually—has been universally positive,” he reports. By comparison, he says, “I’ve had lots of bad experiences with white Americans.”

Lacking reliable evidence for his preferred conclusion, Adams turned to suspicions and intuitions. “If you suspect a group of people has bad feelings about you, you should put some distance between you and that group,” he told his viewers on Sunday. In a separate interview, he posited the scenario of a man applying to a company run by women. Adams said he would advise the man that although “you don’t know what all those women think . . . if your intuition is that they might not favor you” to the same extent as an alternative company run by men, it would be wiser to join the male-dominated company.

There’s a word for staying away from people due to suspicions or intuitions based on their race or gender. The word is prejudice.

2. Segregation deprives you of information about individuals.

On Saturday, Adams advised white people that in the absence of information about specific black people they encountered, the safe course was to assume that these black people were hostile to whites. “Within the black population, there’s a very high percentage of people who don’t like me,” he reasoned. “And since I don’t know which ones it is—and since it’s completely legal for me to move or associate with whoever I want—I will reduce that risk by not being with people who don’t like me.”

But the next day—without acknowledging that he was contradicting himself—he said it would be erroneous to prejudge him that way:

If I were to, let’s say, be introduced to a group of black Americans, especially after the news this week, would I feel comfortable? . . . No, I wouldn’t feel comfortable at all. But would I have any problem with any one person in that group? Maybe for about five minutes. Meaning that anybody who talks to me for five minutes gets a really good reading of what I’m about. . . . In five minutes, you would know that you don’t have a problem with me. It would be obvious, right? So in person, people are pretty good.

Exactly. People who initially fear you based on a superficial impression—color, for example—discover, when they get to know you, that they misjudged you.

On Monday, Adams broadened this point to Republicans and Trump supporters. He suggested that black people would be wise to avoid anti-black racism by staying away from white people who wore MAGA hats. Then, addressing his white viewers, he reconsidered that advice. “Most of you, if you’re Trump supporters, you say, ‘But wait, we’re not racists, don’t do that,’’ he reflected. “And I agree.” Reversing himself, he concluded that conservatives weren’t racists and that “Republicans are actually a pretty good group to live around.”

If you’re white, why not give black people the same chance to disprove your suspicions?

Adams isn’t blind to the perils of prejudgment. On Sunday, he acknowledged that as an employer, you’d be an “idiot” to refuse to interview a job applicant “for a racial reason. A smart person would say, ‘Well, this could be the best employee I’ve ever had.’ You don’t know. So I better find out.”

The lesson is simple: Information about a specific person is better than extrapolation from a group average, and it’s certainly better than free-floating prejudice. So it would be foolish to deprive yourself of direct experience with the person you’re judging. But that’s what social segregation does.

3. Attributions of group prejudice feed the cycle of fear and resentment.

On Sunday, Adams claimed that black people who criticized his rant were proving him right about the wisdom of segregation:

The agreement comes in two forms. One form is black people saying I’m a horrible, horrible person and I should be canceled. That’s my point. . . . My point is that there are way too many . . . black people who have a very negative opinion of white people. That was my point. So the ones who are yelling at me and also black are also making my point.

This is a circular argument: I propose segregation on the grounds that black people are hostile to white people; black people denounce me, a white man, for this proposal; therefore, black people are hostile to white people, and my proposal is vindicated.

Adams tried to deny that that his rant had triggered the denunciations. But he went on to implicate himself, inadvertently, by blaming interracial hostility on polls that divide respondents by race:

The media decided we’re different groups. You know, why does the Gallup poll show black vs. white feelings? They’re dividing us. . . . If every time you pick up the news, the Gallup poll is separating people into black and white, what are you going to do? You’re going to do the same thing. So the division is caused by the media.

The media? It wasn’t the media that had seized on the Rasmussen poll to divide people by race. It was Adams. In his Sunday livestream, without any sense of irony, he held his phone up to the camera to show that mentions of racism in major newspapers had gone “through the roof” since his rant. Given this escalation, he argued, it was logical to “stay away from the people who have been riled up to hate you.”

Riled up, in this case, by the guy holding the phone.

4. Incendiary images feed the cycle of fear and resentment.

In his original rant, Adams didn’t just complain about black hostility to whites. He added:

I’m also really sick of seeing video after video of black Americans beating up non-black citizens. You know, I realize it’s anecdotal, and it doesn’t give me a full picture of what’s happening. But every damn day, I look out at social media, and there’s some black person beating the shit out of some white person. I’m kind of over it. I’m over it. So I quit.

Five days later, Adams cited these videos as a reason why black people should fear white neighborhoods:

There’s so many videos going around of black people beating up non-black people. . . . Wouldn’t you agree—those of you who are black, who are watching this—wouldn’t you agree that’s bad for you? That it’s like programming white people to have a view that’s not representative? So wouldn’t you say that the problem is people being programmed with bad thoughts? . . . Wouldn’t you think twice before you moved into a neighborhood that you thought had been programmed with that frame of mind?

Well, yes. The fear and anger stoked by circulation of these incendiary, unrepresentative videos does make it more likely that black people will worry about white people, and vice versa. That’s one reason why Adams ought to stop hyping these videos and ask himself, instead, how he ended up in a social-media circle where such videos appear every day. He’s contributing to the racial animus that he then invokes as a rationale for segregation.

5. You can’t shun groups without hurting individuals.

Adams agrees that it’s wrong to discriminate against individuals based on race or sex. But he claims that his advice to avoid whole groups “doesn’t have anything to do with individuals.”

This distinction is incoherent on its face: When you avoid a group, you’re avoiding the people in it. But even if you try to behave differently in individual settings from the way you behave in group settings, the mentality of prejudice spills over.

Adams illustrated this problem on Sunday when he groused that the media had “made it impossible for a white person to feel comfortable around a black person.” Immediately, he caught himself and tried to rephrase this as vague guidance that didn’t necessarily apply to everyone. But by then, the problem was exposed: You can’t think like a bigot and then suddenly switch off your bigotry in one-on-one settings.

Consider the question of sex discrimination. On Monday, Adams brought up a rule, notoriously attributed to former Vice President Mike Pence, which Adams described this way: A man shouldn’t have lunch or dinner alone with a woman—including workplace colleagues or other business associates—other than his wife. Adams explained:

Any individual woman is fine. But the class of—the category of people called women have been very much, let’s say, programmed by the #MeToo narrative. . . . So I do recommend that you stay away from women, certainly in a work environment where you’re alone. So I wouldn’t spend time alone with women, because women have been radicalized by the narrative to look for #MeTooing, and they’re going it find it where a man won’t.

If you’re a woman trying to have a business lunch with a man—and he refuses because of this rule—it’s no consolation that he thinks you’re okay as an individual. What matters is that he’ll dine with men, but he won’t dine with you, on account of your gender. Group discrimination is individual discrimination.

Every time one of these racially incendiary arguments comes along, the cycle repeats itself. The offender gets canceled. His opinion is dismissed as unthinkably repellent. He and his allies seize on that dismissal as evidence that the establishment is suppressing dissent. Nothing should be unthinkable, the dissenters argue. There’s some secret truth, some taboo insight, that the cancel culture is hiding from you.

Sorry, but there’s no great insight here. You can watch hour after hour of Adams’s livestreams, as I have, and you won’t find that nugget of forbidden truth. His reasoning is as sloppy as his research. In every way, he’s just wrong.