'The French Dispatch' Review

And an assignment you won't want to skip.

The French Dispatch Review

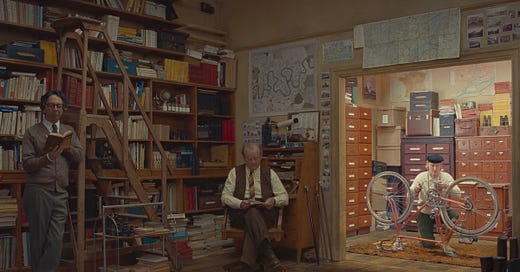

Yes, Wes Anderson’s latest is a love letter to the New Yorker, that august publication that has come to define longform journalism and cultural criticism. Yes, it’s an immaculately fussy collection of costumes and character actors framed by the director in a way that can only be defined as “twee.” And yes, it’s somewhat episodic, more a series of shorts than a proper narrative feature.

But The French Dispatch is best understood as a meditation on art and the processes that go into creating art. The needs of artists and the ways in which the demand for art is created and massaged. The different forms art takes and the ways in which artistry informs a variety of creative endeavors, from paintings to politics, from the culinary to the concrete. It is a paean to editors and all others who nurture—some might say “coddle”—creative talent.

The film comprises four stories: an ode to the town of Ennui, France, by Herbsaint Sazerac (Owen Wilson); “The Concrete Masterpiece,” a consideration of the rise and influence of an imprisoned artist by J.K.L. Berensen (Tilda Swinton); “Revisions to a Manifesto,” an examination of student protests in France by Lucinda Krementz (Frances McDormand); and “The Private Dining Room of the Police Commissioner,” a profile of a police chef by Roebuck Wright (Jeffrey Wright) that evolves into something more exciting and adventurous. The spine connecting all these stories is the life and death of Arthur Howitzer Jr. (Bill Murray), founder and editor of “The French Dispatch.”

Murray plays Howitzer with a sort of benevolent annoyance at the fact that he has to deal with the quirks of the geniuses who make his magazine the most-beloved rag in the land. He’s resigned to treating his writers, as opposed to his artists or his copy editors or the poor lad charged with telling him that it’s just an hour to press time, with patience and leeway even as their stories run long and their copy comes in late.

Great magazines are, of course, an artform in and of themselves. There’s the writing, of course. But there’s so much more: a mixture of topics; a defining sensibility; cartoonists who can distill all of this into one-panel bons mots; layout that deftly combines all of this into a physical object you can hold and admire. Fussiness is at the core of the project.

One imagines patience with fussiness is a subject near and dear to Anderson’s heart, and The French Dispatch is frequently quite fussy. Sometimes to its detriment: the split screens in “The Private Dining Room of the Police Commissioner,” for instance, force us to divide our attention between two immaculately constructed images all while reading subtitles. There’s simply too much going on to take in all at once; it’s the sort of thing you desire to own at home simply so you can pause it and soak it all in.

Assuming, of course, that sort of fussiness is your jam. It is very much not the jam of many people, and I can understand that. But I’d quibble with those who argue that Anderson’s aesthetic obsessions overwhelm this film. Indeed, I would argue that Anderson’s aesthetic obsessions are the heart of the film, its entire reason for being.

How else to interpret the story of imprisoned artist Moses Rosenthaler (Benicio Del Toro) finding fame and fortune both for his abstract interpretation of his guard Simone (Léa Seydoux) and due to the labors of fellow inmate and art dealer Julian Cadazio (Adrien Brody), who creates the demand needed to turn Rosenthaler into a critical and commercial sensation. Of particular interest is the way in which commercial and critical success aren’t in tension but in symbiosis, one feeding off the other.

Or consider Ms. Krementz’s efforts to better the revolutionary manifesto of a young protester, Zeffirelli (Timothée Chalamet). A violation of journalistic neutrality, perhaps, but also a clear and concise reminder that, as Orwell once succinctly put it, “all art is propaganda.” Conversely, all propaganda is, at its best, art, or at least artistically inclined. That Zeffirelli’s propagandistic poetry and prose are almost comically purple is, I think, part of the gag.

And what is fussier than fine dining? Think of the training and time and effort and care—a span that can be measured in years, depending on how you want to look at it—that goes into making something look just-so on the plate before it is consumed in seconds by the patron. Is this not a metaphor for movies writ large? And is there not something poignant about Anderson—the Texas-born boy shooting movies beloved by critics on the coasts—having two outsiders to Ennui, Lt. Nescaffier (Stephen Park) and Roebuck Wright, admit that their greatest fear is failing to live up to the expectations of their adopted homeland’s populace?

Look: I can understand why even Anderson fans might be a bit put off by The French Dispatch. One of the reasons I quite dislike Moonrise Kingdom is that it seems determined to justify all the critiques of Wes Anderson that suggest he’s little more than a guy playing with a living dollhouse. (Also, the portrayal of the relationship between the two kids at the heart of the thing squicks me out a bit.) But his fussiness this time around is in service of the world’s great unsung heroes—editors—so I’ll allow it.

Is there an Anderson skeptic in your life who needs to be convinced to see The French Dispatch? Forward them this review!

Links!

Going to switch things up a bit and highlight some of the cultural writing at The Bulwark this week. Check them out when you have a minute!

Everyone knows you should go see Dune in theaters. And everyone knows that you should see Dune in IMAX. But not everyone knows that there are multiple IMAX formats. In this piece, I walk you through the differences and let you know where to find The Biggest IMAX Theaters. (And don’t forget to listen to Across the Movie Aisle’s show on Dune this week!)

Bill Ryan finished up his series of profiles of horror authors for Halloween with this look at Robert Aickman, an author who “elevated” horror before “elevated horror” was a phrase. (And make sure to read Bill’s previous pieces on Shirley Jackson, Stephen King, and Thomas Ligotti.)

Zandy Hartig, an actress and new addition to The Bulwark’s roster of writers, did a deep dive on a trio of low-budget horror movies from the 1970s. I really hope you check it out, in large part because I love the way Zandy uses her experiences as an actress to inform her appreciation of Let’s Scare Jessica to Death, The Brood, and Suspiria.

Consider this some service journalism: At The Bulwark Goes to Hollywood this week I interviewed Aaron Perzanowski, an academic whose area of interest is ownership in the digital age. And I don’t mean to scare you, but: if you think you own a digital file, you really don’t. Figure out why and how to protect yourself by listening to this episode!

This is not from The Bulwark but it’s not a link—it’s an embed—so I’ll allow it. Bill Murray reads some of the rules from “The Theory and Practice of Editing New Yorker Articles.”

Assigned Viewing: Isle of Dogs (Disney+)

Not necessarily one you should watch with the kiddies, dealing as it does with a potential doggo genocide, but one you should definitely watch. Anderson’s second stop-motion feature (The Fantastic Mr. Fox, also on Disney+, was the first), The Isle of Dogs is suffused with Anderson’s typically whimsical style while also delving into some pretty dark material.

There’s the previously mentioned canine killing, of course, but it’s just a lens through which to view various human conflicts having to do with outsiders and social cleanliness. It is also a fascinating film about the limits and humor inherent to translation, as Moeko Fujii noted in the New Yorker when the movie came out. “The simul-talk devices [in Isle of Dogs], meanwhile, are shown to be operated by shadowy men in white starched shirts,” Fujii writes. “This is the beating heart of the film: there is no such thing as ‘true’ translation. Everything is interpreted. Translation is malleable and implicated, always, by systems of power.”

And this is at least part of the point of The French Dispatch, the idea that the stories we read are refracted through both personal and institutional lenses that have their own interests and their own goals. Frances McDormand’s Krementz shows journalistic neutrality to be a farcical goal in The French Dispatch, but she isn’t the only journalist in that film inappropriately close to her subjects. How a story is translated and who gets to do the translation is a key consideration in any story, journalistic or otherwise.

I also couldn’t stand Moonrise Kingdom, but I’m really happy to have read this review before seeing the movie, because when I do (sometime this weekend) my mindset won’t be so dead set against the whole whimsy of it all. I’d like to enjoy Wes Anderson movies again. Also, anyone else Bill Murray tapped out? He’s like comedy Meryl Streep to me.

I was really interested to learn that I actually saw Dune in one of the biggest Imax theaters, and after reading your article about Imax I think I'm going to see it in Imax again tomorrow.