TNB last night was exceptional. Cathy Young and Eric Edelman shared many insights—about the progress of the war, Putin’s future, historical lessons, and more. You can watch the rewind here or listen to the podcast version here.

Now let’s talk about something nice.

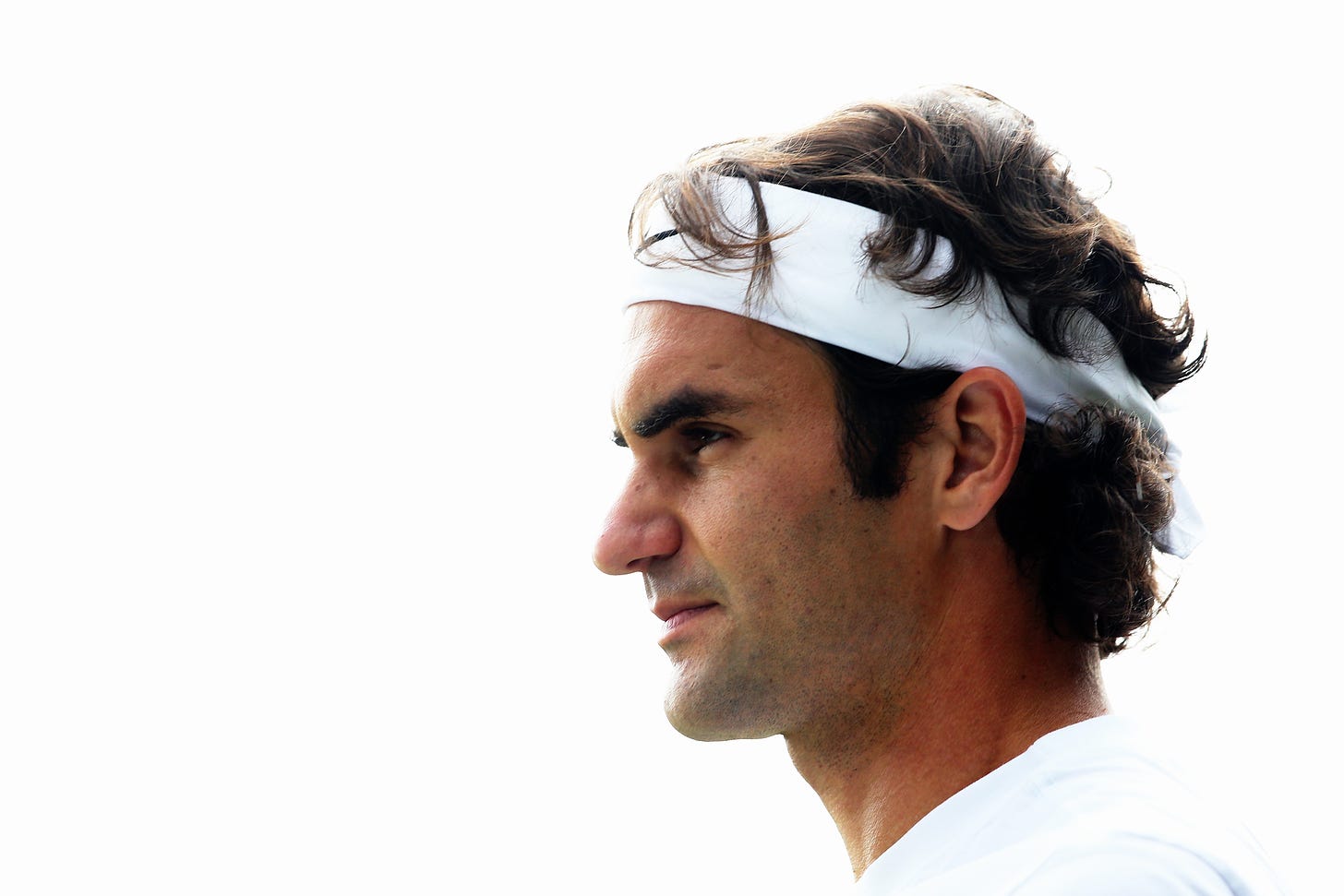

1. The Swiss

My feelings about Roger Federer are not complicated. He is an all-time great. Probably the all-time great. Not only on the court, but off. And yesterday he announced that he’s retiring with exactly the graciousness and thoughtfulness you’d expect.

This is quintessential Federer. Grateful and humble, but not falsely modest. A guy who legit loves tennis. He could have hung it up five years ago, but he stayed in the game not out of habit or covetousness, but because he flat-out enjoys every aspect of it. The training. The atmosphere. The sport.

We’ll talk about the GOAT conversation in a minute, but first I want you print out or bookmark David Foster Wallace’s seminal profile of Federer: “Roger Federer As Religious Experience.”

Here is DFW appraising this shot in the 2005 US Open final:

Federer had to send that ball down a two-inch pipe of space in order to pass him, which he did, moving backwards, with no setup time and none of his weight behind the shot. It was impossible. It was like something out of “The Matrix.”

There are others. Federer was such an otherworldly shotmaker that, in a career of more than 1,500 matches there are plenty of individual shots people remember. My own favorite—the shot that still blows my mind—came against Andy Roddick in 2002.

Here is what happened:

Roddick booms one of his big serves, jamming Federer against his body. Federer does well to return it in play, but the ball is short and Roddick is already coming in. Roddick hits an approach from the T, but doesn’t do enough with it. Federer uncorks a forehand to pass and Roddick makes a desperate stab. He’s lucky. He gets luckier still when Federer pops up a weak backhand lob. Roddick crushes it, sending the bounce soaring toward the stands in the far-court’s left-hand corner. The point is over.

Except that it’s not. Federer is still moving. He tracks the flight of the ball’s bounce. He’s gliding in the way that he does, where he looks effortless, but he’s covering court at remarkable rate. All the way to that back corner. He’s five feet away from the wall—in baseball, he’d be on the warning track—when he jumps, turns 90 degrees in the air, and hits an overhead, while still facing the wrong way, for a down-the-line winner.

Roddick, understanding that what he has just seen is not possible, half-heartedly throws his racket at Federer. What else are you supposed to do when the guy you’re playing has the ability to warp space-time?

Watch for yourself right here.

Back to DFW:

Federer’s forehand is a great liquid whip, his backhand a one-hander that he can drive flat, load with topspin, or slice — the slice with such snap that the ball turns shapes in the air and skids on the grass to maybe ankle height. His serve has world-class pace and a degree of placement and variety no one else comes close to; the service motion is lithe and uneccentric, distinctive (on TV) only in a certain eel-like all-body snap at the moment of impact. His anticipation and court sense are otherworldly, and his footwork is the best in the game — as a child, he was also a soccer prodigy. All this is true, and yet none of it really explains anything or evokes the experience of watching this man play. Of witnessing, firsthand, the beauty and genius of his game. You more have to come at the aesthetic stuff obliquely, to talk around it, or — as Aquinas did with his own ineffable subject — to try to define it in terms of what it is not. . . .

There are three kinds of valid explanation for Federer’s ascendancy. One kind involves mystery and metaphysics and is, I think, closest to the real truth. The others are more technical and make for better journalism.

The metaphysical explanation is that Roger Federer is one of those rare, preternatural athletes who appear to be exempt, at least in part, from certain physical laws. . . . And Federer is of this type — a type that one could call genius, or mutant, or avatar. He is never hurried or off-balance. The approaching ball hangs, for him, a split-second longer than it ought to. . . .

This thing about the ball cooperatively hanging there, slowing down, as if susceptible to the Swiss’s will — there’s real metaphysical truth here. And in the following anecdote. After a July 7 semifinal in which Federer destroyed Jonas Bjorkman — not just beat him, destroyed him — and just before a requisite post-match news conference in which Bjorkman, who’s friendly with Federer, says he was pleased to “have the best seat in the house” to watch the Swiss “play the nearest to perfection you can play tennis,” Federer and Bjorkman are chatting and joking around, and Bjorkman asks him just how unnaturally big the ball was looking to him out there, and Federer confirms that it was “like a bowling ball or basketball.” He means it just as a bantery, modest way to make Bjorkman feel better, to confirm that he’s surprised by how unusually well he played today; but he’s also revealing something about what tennis is like for him. Imagine that you’re a person with preternaturally good reflexes and coordination and speed, and that you’re playing high-level tennis. Your experience, in play, will not be that you possess phenomenal reflexes and speed; rather, it will seem to you that the tennis ball is quite large and slow-moving, and that you always have plenty of time to hit it. That is, you won’t experience anything like the (empirically real) quickness and skill that the live audience, watching tennis balls move so fast they hiss and blur, will attribute to you.

So is Federer the GOAT? It’s not an open-and-shut case. But I think yes.

Consider the question this way: If your life depended on the outcome a tennis match and you could pick any player, in his absolute prime, to play it for you, who would you go with?

The short list is awfully short. Laver. Sampras. Federer. Nadal.1

Of those, I’d take Federer, without hesitation. His best day was better than anyone else’s best day, ever. No one has ever played the game at the level he did.

If you assess GOAT status more as a “totality of career accomplishments” question, then there’s more competition. Laver has the Slam. Nadal has more major victories. So does (ugh) Djokovic.

I probably take Federer over Nadal here, by a nose. One of the weirdnesses of their careers is that had Federer and Nadal not played in the same era, then they each might have won something like 35 majors.

But of all the numbers about Federer, the one that stands out most is this: Between 2004 and 2010 he reached 23 consecutive Grand Slam semifinals.

This achievement will never be broken. It’s like DiMaggio’s 56-game hitting streak and Ripken’s 2,632-game iron horse streak, rolled into one.

So farewell to Federer. He is one of the rare athletes who gave even more to the game than the game gave him.

2. Martha’s Vineyard

There were two prevailing arguments made by conservatives over Ron DeSantis’s stunt yesterday:

DeSantis was doing the humane thing by sending these Venezuelan immigrants to a state better equipped to accommodate them.

DeSantis was acting out of spite and teaching the libs a lesson by showing them how awful immigrants are.

Both presuppose that immigration is ruining border states such as Texas and Florida(?), turning them into hellholes that real American citizens barely recognize.

The problem with this line of argument is that both Ron DeSantis and Texas Governor Greg Abbott are running for reelection on the premise that their states are doing great. That Texas and Florida are beacons to the rest of the country, showcasing the magnificent blessings of freedom and liberty—with Texans and Floridians being lucky to have these states as their homes.

So which is it?