President Trump’s lawyers threw one bogus theory after another against the wall in arguing against calling witnesses in Trump’s Senate impeachment “trial.” Of course, a trial in which the prosecutors can’t call witnesses or introduce documents isn’t really a trial; perhaps it’s best to think of it as a Very Serious Gathering.

All of the arguments, save one, are so ludicrous that they would have been laughed out of court in any criminal or civil trial anywhere in the country. The one argument that might survive the giggle test isn’t much better. It holds that conditioning an official act on receipt of a personal favor—in other words, an act of extortion—isn’t impeachable on its face.

And that’s the serious argument. Let’s take a look at the unserious arguments offered by Trump’s defenders.

The House managers claimed that they had overwhelming evidence, beyond any doubt, that Trump was guilty as charged. Therefore could not at the same time claim that they needed to call new witnesses.

Every prosecutor comes into every case contending that there is proof beyond a reasonable doubt of the defendant’s guilt. Indeed, bringing a criminal charge without that belief is an egregious ethical violation.

In response to the prosecution’s contention, defendant’s who go to trial argue that the evidence against them is insufficient.

Nota bene: This is defense is not argument against presenting evidence at the trial. It’s the argument for presenting the evidence.

In this case, Trump’s defenders argued that there was no quid pro quo and that all of the incriminating evidence was second-hand and hearsay. Calling witnesses with direct, first-hand knowledge of Trump’s linking aid to political favors would have been the best, and perhaps the only way to conclusively resolve this factual dispute.

Trump’s lawyers didn’t have an opportunity to call or cross-examine witnesses when the House obtained most of its evidence.

This is factually true, but neither unusual nor even relevant to the question of whether or not witnesses should be allowed at the Senate trial.

The target of a criminal investigation never gets to call or cross-examine witnesses during the pre-indictment investigative phase of a criminal proceeding. Prosecutors routinely present testimony to grand juries in secret. Much of the time, the target doesn’t even know that the investigation is taking place, much less have an opportunity to participate in it.

In this case, there was no investigation by the Department of Justice and no special counsel report on which the House could rely in deciding whether or not to impeach the president. So the House had to conduct its own investigation.

And it did so in a manner more favorable to the target than would normally be allowed.

While the president’s counsel didn’t participate personally, Trump’s congressional defenders were not only present when witnesses were questioned, but were given the opportunity to participate actively. Criminal defendants could only dream of being given that sort of access during the pre-indictment, investigative phase.

Now, an impeachment proceeding is not a criminal trial. But that being said, there is no legal or principled basis which required the House to grant the president the right to call and question witnesses during the course of its pre-indictment investigation.

There’s nothing in the Constitution, no statute, no House rule, and no case law supporting such a proposition.

The fact that there is some scant precedent for allowing such participation doesn’t make it mandatory. And the so-called precedents—the Nixon and Clinton impeachment proceedings—are highly distinguishable because in each of those cases thorough investigations were performed by independent special counsels before the House even began its deliberations.

All witnesses called in earlier impeachment trials in the Senate had already given testimony to the House, or grand juries, or in special investigations. That wasn’t true of the witnesses the House managers wanted to call in this case, so they should not be allowed to call them.

Trump’s argument against calling witnesses who didn’t testify in the earlier House proceedings is somewhat akin to what lawyers call a “failure to exhaust other remedies” defense. Some laws and caselaw require the exhaustion of lesser administrative or other remedies prior to asserting a claim in court.

But there is nothing in impeachment jurisprudence (or common sense) supporting this “do it in the House or you’re forever prohibited from doing it in the Senate” argument.

There is no constitutional provision, statute, or court decision—anywhere—which holds, or even suggests, that in a Senate trial, the House can only call witnesses who have previously testified.

In any other trial—criminal or civil—the prosecutor/plaintiff may subpoena any witness who has relevant information to testify at trial, provided only that adequate notice has been given. Witnesses who have never given previous testimony are called to testify at trial every day in the United States.

Nor is there any precedent for a different rule to apply in an impeachment.

The fact that previous House prosecutors may have chosen not to call witnesses who hadn’t already testified (if that is in fact the case) doesn’t mean that all subsequent House managers can’t do so. And two presidential impeachment cases that have gone to the Senate over a 150-year span under wildly different circumstances is a very thin reed on which to hang legal “precedent.”

There might be some claim to precedent if, in either of the previous impeachment trials, the House managers had been prevented from calling witnesses who hadn’t testified previously. But that isn’t the case. No such ruling has ever been made in any previous presidential impeachment trial.

It will take too long.

The mere possibility that Trump might claim “absolute immunity” or executive privilege isn’t a reason not to call witnesses.

Any witnesses subpoenaed to testify either would, or would not, appear, and either would, or would not, refuse to answer some of the questions they were asked.

If some witnesses refused to honor Senate subpoenas, the Senate would retain the option to seek expedited court enforcement or to simply move on without that witness’s testimony—if it appeared that the process would cause undue delay. But that’s a decision that can and should be made at the time, not in advance.

John Bolton, for instance, made it clear that he would appear to testify if he received a subpoena, so refusal to honor the subpoena wouldn’t even have been an issue in his case.

And if Trump’s legal team asserted executive privilege in an attempt to prohibit a witness from answering any given question, it would initially be up to the witness to either honor or reject that claim. If the witness attempted to accede to the privilege claim, then the presiding officer, the chief justice of the Supreme Court, could either agree, or reject the privilege claim. And all the while, the witness would be able to answer other key questions, perhaps not about direct conversations with Trump and therefore not subject to a claim of executive privilege, that would support (or discredit) the allegations in the articles of impeachment.

Basing the radical decision to prevent a prosecutor from calling witnesses at what is supposed to be a trial on a worst-case fantasy about the possibility of delay—due to circumstances that might or might not occur, and could be easily dealt with if they did—is bogus.

It’s an election year.

If we were only days or weeks away from a presidential election, this might be a prudential reason to exercise restraint. Or it might not, depending on the nature of the charge.

But we’re not. We’re nine months away, and the nature of this impeachment proceeding goes directly to the heart of whether this president should be given a green light to extort foreign actors into interfering with the election on his behalf.

Moreover, the very idea that we should “let the voters decide” whether a president has committed an impeachable offense is both preposterous and unconstitutional. If the framers had wanted the voters to decide whether or not to remove a president after impeachment in the House, it would have mandated a national plebiscite on the articles of impeachment and not granted the sole authority to try the case to the Senate.

Even if entirely true, the allegations against Trump would not rise to the level of an impeachable offense. Therefore, there is no need to call witnesses to either prove or rebut them.

Of all of Trump’s arguments against calling witnesses, this is the only one that has theoretical merit. But if fails as applied to this specific case.

It is not uncommon for defendants to argue that they are entitled to judgment in their favor without the presentation of witnesses or other evidence because the allegations against the defendant, even if accepted as entirely true, are insufficient to state a claim.

In such cases, the defendant may “demur,” or move to dismiss for failure to state a claim. Or move for summary judgment on the ground that there are no material facts in dispute.

In other words, the defense lawyer assumes for the sake of argument (but doesn’t admit) that the facts alleged against the defendant are true, but nevertheless argues that they are insufficient to support the claim.

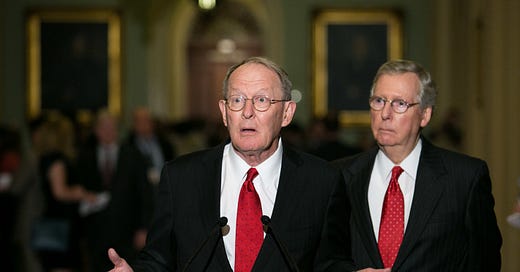

That’s essentially the Lamar Alexander position.

But doing so in this case requires accepting a dubious legal interpretation advanced by Alan Dershowitz, or something like it. And that interpretation is as dangerous as it is baseless.

Dershowitz argued that the Framers would have rejected “abuse of power” as an impeachable offense, although they never got around to it.

He gets there by rewriting the Constitution. The constitutional standard for impeachment is “Treason, Bribery, or other high Crimes and Misdemeanors.” Dershowitz argues that these words require “crime-like” actions, or actions “akin to” treason or bribery. In other words, Dershowitz effectively substitutes the word “similar” for the actual word in the Constitution, “other.”

“Other,” of course, means, well, other.

Dershowitz simply made up a standard that appears nowhere in the Founders’ debates about impeachment, and nowhere in the jurisprudence in the over 200 years since.

How did Dershowitz stumble upon this newly minted standard? As Adam White explained last week, with selective quotations and misdirection.

First, he concluded that “malfeasance,” a standard expressly rejected by the framers, is the same thing as “abuse of power.” Of course it isn’t. Malfeasance is a much broader term that may include abuse of power but goes much farther. Nobody believed then, or believes now, that a president can be impeached for doing a bad job, which is the broadest interpretation of malfeasance. Rejecting malfeasance as a standard isn’t the same as rejecting a corrupt abuse of power.

Then comes the capper. According to Dershowitz, abuse of power must be rejected as a standard because it is too broad and amorphous a concept. Unlike “crime-like,” the standard Dershowitz made up, which is obviously a term of diamond-etched precision. Really, you can’t make this stuff up.

I’m not a constitutional scholar. (By the way, neither is Alan Dershowitz). Honing-in on the precise interpretation of the impeachment clause is above my pay grade and beyond my expertise. But it doesn’t take an expert to recognize that the Dershowitz interpretation, which is contrary to the interpretation of virtually every real constitutional scholar, is hogwash.

And it doesn’t take a Harvard Law professor to understand that it is Trump’s alleged conduct, not anybody’s characterization of it, that should control whether or not he should be impeached.

The conduct alleged—and at least in Lamar Alexander’s judgment proven—is clear and straightforward: Trump conditioned an official act (the release of congressionally-appropriated military aid to Ukraine) on the receipt of a private “favor” (asking Ukraine to publicly smear his likely opponent in the 2020 election).

Only by focusing on the straw man of how the House managers characterized that conduct, rather than on the conduct itself, could one argue with a straight face that what Trump did was not impeachable.

Hopefully, when history gets around to rendering the ultimate verdict on the Trump impeachment, Trump’s defense will be remembered for what it was: an anomalous artifact of a time of polarization so extreme that it is unworthy as being understood as anything other than a curiosity, entirely lacking in any precedential value.

Or perhaps even as a negative precedent.

Otherwise, we’re in big trouble.