The Grim Pandemic Outlook for Fall and Winter

No one likes COVID lockdowns but for many states there may not be a choice.

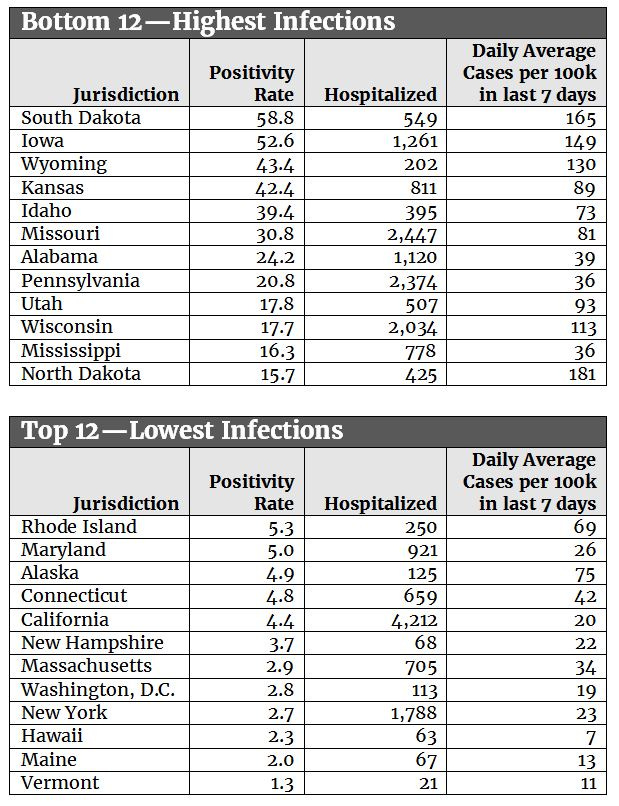

In April 2020, when the first COVID-19 surge was peaking, the United States hit a high of roughly 34,000 positive daily tests. Over the next two months, the crisis subsided to under 20,000 cases per day before spiking to around 75,000 in mid-July, more than double the April peak. The late-summer “lull” of 34,000 daily infections, reached on September 13, was equal to the peak of the spring surge. What this data suggests is that over the past nine months, the United States has been quietly building momentum toward a huge fall/winter outbreak. The full burden of a mismanaged pandemic is now bursting upon us. On election day, the United States recorded about 86,000 new COVID-19 infections. Not even two weeks have passed since then, but the figure has leapt to around 140,000 daily infections. This approaches a doubling of the highs touched in July and there’s nothing to suggest the curve is anywhere near its peak. The United States has also blown past its previous grim hospitalization peak (60,000 in April) rising above 67,000 in the last two days. Improvements in treatment and medicine have helped to cut COVID’s fatality rate significantly (although it is still six times the death rate associated with seasonal flu) but we continue to hover around 1,000 deaths daily, a figure that is sure to rise in the wake of mounting infections and hospitalizations. There’s no place in the country that isn’t struggling with COVID right now, but some places are in a much better position than others. New England, Maryland, California, New York, New Jersey, and Washington, D.C. have maintained low infection rates. These jurisdictions have, without question, paid a high price economically and their joblessness rates continue to exceed the national unemployment rate. However, they kept infections low by imposing strict controls early and then gradually reopening with robust testing and contact tracing, allowing these states to identify emerging hotspots and target restrictions to cities and even zip codes where they are most needed, thus limiting outbreaks and minimizing further economic disruption.

On the other hand, states like Idaho, Iowa, North and South Dakota, Missouri, Utah, and Wisconsin refused to take the most difficult steps to slow the rate of spread in their communities. They are increasingly paying the price of inaction. Positive tests rates, which public health officials have urged be kept under 5 percent, have soared into the double digits—reaching previously unheard of highs of 54 and 48 percent in in South Dakota and Iowa respectively. Kansas is reporting positivity rates over 41 percent and Idaho has hit 40 percent. As predicted earlier this year, health workers and hospitals are being pushed close to their limits in many areas of the country. North Dakota announced last week that its entire hospital system is full and took the extraordinary step of asking COVID-infected staff without symptoms to stay on the job. The governor of Indiana re-imposed restrictions on businesses and individuals, pleading with Hoosiers to prevent a wave of infections from swamping hospitals. Some observers argue these infection rates are largely meaningless as they are not being accompanied by rising mortality rates. To these people, we have just one word: wait. According to the public health models, there is roughly a three-week lag between spikes in infection and deaths. In December, we’ve been told to expect daily deaths will rise to between 1,200 and 2,100 as infections lead to hospitalizations, complications, and deaths. Since infections and hospitalizations are rising so quickly, the number of deaths is likely to continue rising for months. The worst is very much yet to come. The question at the moment is how we get through the next several months. For the worst-affected areas, it may be impossible to avoid significant restrictions on business and other social contacts. In other words, lockdowns. This will be extremely difficult in light of the way COVID has infected politics and vice versa. Take Sioux Falls, South Dakota, afflicted with one of the earliest, worst, and most persistent COVID-19 outbreaks in the country. With its hospitals bursting at the seams, the city council rejected a local masking ordinance last week by a 5-4 vote on the logic that any public health gains would be offset by increasing divisions in the community. Similar battles are being seen elsewhere, such as in El Paso, where city, county, and state officials are fighting each other over public health measures as hospitals and temporary morgue spaces fill up. This kind of nonsense has to stop if any progress is to be made.

Data from 12:30 a.m. on November 15, 2020.

Positivity rate: https://coronavirus.jhu.edu/testing/tracker/overview

Hospitalizations: https://covidtracking.com/data/

Daily Avg Cases per 100k in last 7 days: https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2020/us/coronavirus-us-cases.html

Regarding positivity rates, see also this note: https://covidtracking.com/blog/test-positivity-in-the-us-is-a-mess As is visible in the tables above, a chaotic and irrational approach to pandemic management is having very large, real-world impacts. So-called “red” states that resisted stringent measures like lockdowns are much more likely to be in the soup right now than “blue” states that have enacted more aggressive mitigation strategies. The leadership of high-infection states have, unfortunately, characterized opposition to social distancing, masking, and shutdowns as “freedom” and counterprogrammed such measures as “socialism.” As we noted in August, there’s a symbiotic relationship between a state’s electorate, its governance, and the severity of the pandemic there. Those with the deepest “red” voters and governance have tended to experience the highest levels of infection, while those with deep “blue” governance have tended to experience the least. In perhaps the highest irony of our current situation, several of the best-performing states—Massachusetts, Vermont, Louisiana, and Maryland—are ones in which parties share power. Divided pandemic government, it turns out, may be the best pandemic government. As with so many other facets of public life, the circumstances surrounding COVID combine tragedy and farce. The truth is that tough early mitigation policies, combined with serious testing and tracing programs, were probably the best chance we had to balance public health, individual freedom, and avoidance of even tougher requirements in the future. Especially for states that succumbed to our toxic national political environment and failed to slow the spread of disease, that future is now.