The Hard Facts on Hard Time

We need to align criminal justice policy with today’s realities.

Although the protests and civil unrest that followed the police killing of George Floyd have mostly waned, there remains a widely held belief that both our criminal justice policies and our attitudes about crime and punishment are fundamentally out of sync with reality.

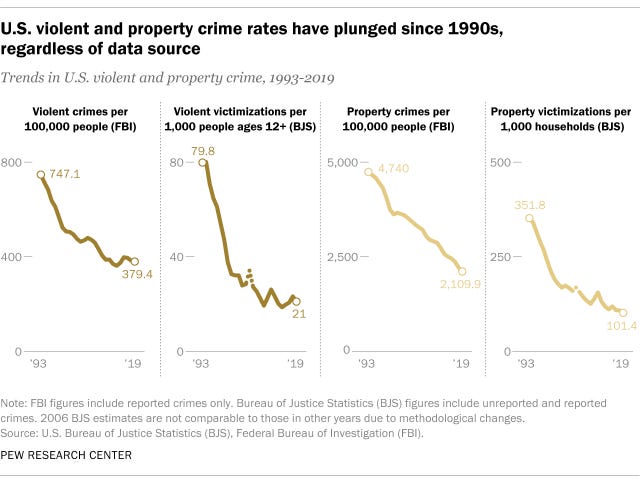

According to the FBI, violent crime has fallen for the third consecutive year, and it has dropped by over 50 percent since the 1990s. Incarceration for youth and adults is down as well, with a 7 percent decline in the prison population from 2009 to 2017. In 2015, arrests for violent crimes by young people hit the lowest rates in around 30 years, and since 2000 youth incarceration has fallen by a whopping 60 percent. We don’t know exactly what’s caused this shift toward lower rates of crime, but the current cohort of young people are committing crimes at a significantly lower rate than their predecessor cohort. In terms of actual crime, America today looks a lot like the 1950s but it has criminal justice policies and systems attuned to the crime wave of the 1980s and early 1990s.

The decline in crime and incarceration suggests a need for new ways of thinking about how we respond to crime as a society. “Get tough” rhetoric still moves voters, but it long ago hit the point of diminishing returns in creating safer communities. To put it bluntly, if these trends in crime and incarceration continue we will have, at least in some places and for some populations, a distended prison system built for a crime problem that no longer exists. As a matter of efficiency, effectiveness, and humane policymaking, further reductions in crime and incarceration will require new policies and strategies that shift from punishment to prevention and rehabilitation.

We may be able to glean some clues about how to do that from incarcerated people themselves. Recently, the Marshall Project conducted a survey of nearly 2,400 incarcerated men and women asking what they thought might have helped them avoid criminal activity. Their responses suggest that tougher penalties and sentences are losing deterrent power. Instead they talked about wishing they had had someone who could have helped them realize their own worth and agency, promoting desistance from within rather than relying on the external restraints of arrest and incarceration.

Some respondents focused on practical questions like the need for affordable housing, vocational training, lower cost college, and a better job market. The problem is that most research suggests such factors are not “criminogenic” and that spending money on them appears to have little or no effect on the propensity to commit crime.

So if a job or a home or education and training don’t make a difference, what does? Around 37 percent of federal and state inmates have received a mental health diagnosis, likely a small fraction of the prison population who could benefit from mental health treatment. Many of the Marshall Project interviewees said access to mental health and psychiatric services would have helped them cope with depression, post-traumatic stress disorder, and other mental illnesses that are associated with criminal behavior. Drug treatment was another high priority, which is unsurprising when nearly half a million people are incarcerated for drug-related offenses. Still others hoped for a life coach, mentor, or parental figure who could encourage them to stay out of trouble. Taken together, these needs suggest that our prisons are full of people who need specific medical and psychological treatment to help them develop stronger connections—to a positive vision of themselves and prosocial relationships with others—that can help them overcome a lifetime of trauma, including the trauma of incarceration.

The idea of focusing on transforming the inner lives of people to prevent crime and promote rehabilitation will strike many people as too “soft,” too focused on “feelings” at the expense of the cold, hard facts of crime and punishment. This perspective overlooks how our current criminal justice policy is also driven mainly by feelings: fear, a need for security and control that hasn’t caught up to current conditions, and a thirst for punishment and revenge. That these responses grow out of a human desire for justice and order does not mean they are any more correct than those who react to systemic injustice with equally unrealistic and potentially damaging calls to defund, and in some cases dismantle, the police. When it comes to refurbishing our policy approaches, it would be far better if we allowed the data to speak rather than listening only to our more primal instinct for punishment.

People always have choices about whether they commit crimes, and police, courts and prisons will always be necessary to isolate bad actors from society and punish wrongdoing. But it’s increasingly clear that policing and punishment alone cannot deliver the safer, more peaceful, and healthier society we all desire. As Congress and the incoming Biden administration take up the challenge of criminal justice reform, we all need to open our minds and our hearts to the possibility that we have reached the end of the road on coercion-and-punishment-focused anti-crime policy. Instead, we need to start asking some deeper questions about how all sectors of our society—government, business, and community and religious organizations—can help individuals, families, and neighborhoods fill the empty hearts that gives rise to crime in the first place.